Clinical Assessment

- Learning Objective

- Introduction

- Clinical Presentation

- Clinical Evaluation

- Exposure History and Physical Examination

- Signs and Symptoms - Acute Exposure

- Signs and Symptoms - Hours to Days after Acute Exposure

- Signs and Symptoms - Several Months after Acute Arsenic Exposure

- Signs and Symptoms - Chronic Exposure

- The Toxicity of Arsine Gas

- Laboratory Tests

- Key Points

- Progress Check

Patients who have been exposed to arsenic in whom toxicity is suspected should undergo a thorough medical evaluation. Early and accurate diagnosis is important in deciding appropriate care strategies, even if the patient is not exhibiting symptoms. In cases of significant arsenic exposure, medical evaluation should include

- an exposure history,

- a medical history,

- a physical examination, and

- additional laboratory testing as indicated.

This section focuses on activities, which are typically conducted during the patient’s visit to clinical office. Recommended tests are discussed in the next section.

Arsenic-associated diseases typically have a long latency period, so that many patients exposed to arsenic are asymptomatic for years. Clinical manifestation of target organ toxicity is based on

- route of exposure,

- dose,

- chemical form,

- frequency, duration, and intensity of exposure, and

- time elapsed since exposure.

A single patient can develop any combination of arsenic-associated diseases.

In chronic exposures, particular clues to arsenic poisoning may be provided by dermatologic and neurologic findings. The exposure history should include

- condition of household pets,

- diet (emphasis on frequency, amount, and type of seafood ingestion),

- hobbies (including use of old supplies of pesticides or herbicides in farming or gardening),

- home heating methods (wood burning stoves and fireplaces and source of fuel),

- medications (including folk, imported, homeopathic or naturopathic medications),

- occupational history,

- residential history (proximity to former smelters, other industry, former orchards and farms, and hazardous waste sites), and

- source of drinking water.

A sample exposure history form can be found in the ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Taking an Exposure History

In acute arsenic poisoning, death is usually due to cardiovascular collapse and hypovolemic shock. The fatal human dose for ingested arsenic trioxide is 70 to 180 milligrams (mg) or about 600 micrograms per kilograms (kg)/day [ATSDR 2007].

- Onset of peripheral neuropathy may be delayed several weeks after the initial toxic insult.

- Mee’s lines may be visible in the fingernails several weeks to months after acute arsenic poisoning. Mee’s lines are transverse white lines across the nails [Rossman 2007].

Acute arsenic poisoning occurs infrequently in the workplace today; recognized poisoning more commonly results from unintentional ingestion, suicide, or homicide.

The fatal dose of ingested arsenic in humans is difficult to determine from case reports, and it depends upon many factors (e.g., solubility, valence state, etc.).

The minimal lethal dose is in the range of 1 to 3 mg/kg [ATSDR 2007].

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003-2004) measured levels of total arsenic and speciated arsenic in urine of a representative sample of the U.S. population. The data reflect relative background contributions of inorganic and seafood-related arsenic exposures in the U.S. population [Caldwell et al. 2008]. See “Laboratory Tests” in this section for more details.

As a result of inorganic arsenic’s direct toxicity to the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract and its systemic enzyme inhibition, profound gastroenteritis, sometimes with hemorrhage, can occur within minutes to hours after ingestion.

The signs and symptoms of acute and subacute arsenic poisoning include

- Gastrointestinal

- garlic odor on the breath,

- severe abdominal pain,

- nausea and vomiting,

- thirst,

- dehydration,

- anorexia,

- heartburn,

- bloody or rice water diarrhea, and

- dysphagia.

- Dermal

- delayed appearance of Mee’s lines in nail beds,

- dermatitis,

- melanosis, and

- vesiculation.

- Cardiovascular

- hypotension,

- shock,

- ventricular arrhythmia,

- congestive heart failure,

- irregular pulse, and

- T-wave inversion and persistent prolongation of the QT interval.

- Respiratory

- irritation of nasal mucosa, pharynx, larynx, and bronchi,

- pulmonary edema,

- tracheobronchitis,

- bronchial pneumonia, and

- nasal septum perforation.

- Neurologic

- sensorimotor peripheral axonal neuropathy (paresthesia, hyperesthesia, neuralgia),

- neuritis,

- autonomic neuropathy with unstable blood pressure, anhidrosis, sweating and flushing,

- leg/muscular cramps,

- light headedness,

- headache,

- weakness,

- lethargy,

- delirium,

- encephalopathy,

- hyperpyrexia,

- tremor,

- disorientation,

- seizure,

- stupor,

- paralysis, and

- coma.

- Hepatic

- elevated liver enzymes,

- fatty infiltration,

- congestion,

- central necrosis,

- cholangitis, and

- cholecystitis.

- Renal

- hematuria,

- oliguria,

- proteinuria,

- leukocyturia,

- glycosuria,

- uremia,

- acute tubular necrosis, and

- renal cortical necrosis.

- Hematologic

- anemia,

- leukopenia,

- thrombocytopenia,

- bone marrow suppression, and

- disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- Other

- rhabdomyolysis and

- conjunctivitis.

Descriptions of potential signs and symptoms of subacute or delayed arsenic poisoning by time lapsed since acute exposure include

- Gastrointestinal

- Symptoms may last for several days.

- Difficulty in swallowing, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration may result.

- However, in subacute poisoning the onset of milder GI symptoms may be so insidious that the possibility of arsenic intoxification is overlooked.

- Cardiac and Vascular System

- As previously mentioned, arsenic has deleterious effects on the heart and peripheral vascular system.

- Capillary dilation with fluid leakage and third spacing may cause severe hypovolemia and hypotension.

- Cardiac manifestations have included

- cardiomyopathy,

- ventricular dysrhythmias (atypical ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation), and

- congestive heart failure.

- Neurologic

- A delayed sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy may occur after acute arsenic poisoning.

- Symptoms are initially sensory and may begin 2 to 4 weeks after resolution of the first signs of intoxication resulting from ingestion (shock or gastroenteritis).

- Commonly reported initial symptoms include numbness, tingling, and “pins and needles” sensations in the hands and feet in a symmetrical “stocking glove” distribution, and muscular tenderness in the extremities.

- Clinical involvement spans the spectrum from mild paresthesia with preserved ambulation to

- distal weakness,

- quadriplegia, and,

- in rare instances, respiratory muscle insufficiency.

- Other findings of subacute arsenic poisoning may include

- fever and

- facial edema.

Signs and symptoms several months after acute arsenic poisoning include

- Transverse white striae (pale bands) in the nails called Mee’s lines (or Aldrich–Mee’s lines) may be seen, reflecting transient disruption of nail plate growth during acute poisoning.

- In episodes of multiple acute exposures, several Mee’s lines may occur within a single nail.

- In some cases, the distance of the lines from the nail bed may be used to roughly gauge the date of the poisoning episode.

- However, Mee’s lines are not commonly seen.

- Respiratory tract irritation.

- Cough, laryngitis, mild bronchitis, and dyspnea may result from acute exposure to airborne arsenic dust.

- Nasal septum perforation, as well as conjunctivitis and exfoliative dermatitis, has also been reported.

- Other.

- Reversible anemia and leukopenia may develop [Rosenman 2007].

Skin lesions and peripheral neuropathy are the most suggestive effects of chronic arsenic exposure (via inhalation or ingestion). Their presence should result in an aggressive search for this etiology. In addition, neuropathy can occur insidiously in chronic toxicity without other apparent symptoms. However, careful evaluation usually reveals signs of multi organ and multi system involvement such as

- anemia,

- leukopenia, and/or

- elevated liver function tests.

Dermal

- Hyperpigmentation is the most sensitive endpoint for arsenic exposure, but does not occur in every individual. This may suggest genetic susceptibility [Yoshida et al. 2004; Guha 2003].

- Pigment changes occur most often on the face, neck, and back [Yoshida et al. 2004; Guha 2003].

- Skin lesions are the earliest nonmalignant effect of chronic exposure [Yoshida et al. 2004; Guha 2003].

- Skin hyperpigmentation and hyperkeratosis are delayed hallmarks of chronic arsenic exposure.

- Pigment changes include areas of hyperpigmentation interspersed with smaller areas of hypopigmentation that give a “raindrop” appearance on the trunk and neck [Tseng et al. 1968; Centeno et al. 2002].

- Hyperkeratosis of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (palmoplantar hyperkeratosis) look like small corn-like elevations and diffuse keratosis [Tseng et al. 1968; Centeno et al. 2002].

- Desquamation can also be seen.

- Skin lesions may take a long time to manifest (3 to 7 years for pigmentation changes and keratoses; up to 40 years for skin cancer) and may occur after lower doses than those causing neuropathy or anemia [ATSDR 2007].

- Hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation are not commonly seen in arsenic inhalation exposures [Rossman 2007].

Neural

- Neuropathy may be the first sign of chronic arsenic toxicity.

- Polyneuritis and motor paralysis, specifically of the distal extremities, may be the only symptoms of chronic arsenic poisoning [Guha 2003].

- Hearing loss, mental retardation, encephalopathy, symmetrical peripheral polyneuropathy (sensorimotor resembling Landry-Guillain-Barre syndrome), and electromyographic abnormalities.

- Both sensory and motor neuron peripheral neuropathy can be seen after chronic inhalation of arsenic and more sporadically with chronic ingestion of arsenic [Rossman 2007].

Gastrointestinal (GI)

- In chronic poisoning, GI effects are generally less severe and may include

- esophagitis,

- gastritis,

- colitis,

- abdominal discomfort,

- anorexia,

- malabsorption, and/or

- weight loss.

Hepatic

- Enlarged and tender liver along with increased hepatic enzymes were found in several studies of chronically exposed individuals [Guha 2003].

- Cirrhosis.

- Portal hypertension without cirrhosis.

- Fatty degeneration.

Hematological

- Bone marrow hypoplasia.

- Aplastic anemia.

- Anemia.

- Leukopenia.

- Thrombocytopenia.

- Impaired folate metabolism.

- Karyorrhexis.

- Anemia often accompanies skin lesions in patients chronically poisoned by arsenic.

Cardiovascular

- Arrythmias.

- Pericarditis.

- Blackfoot disease (gangrene with spontaneous amputation).

- Raynauds syndrome.

- Acrocyanosis (intermittent).

- Ischemic heart disease.

- Cerebral infarction.

- Carotid atherosclerosis.

- Hypertension.

- Microcirculation abnormalities.

Respiratory

- Rhino-pharyngo-laryngitis.

- Tracheobronchitis.

- Pulmonary insufficiency (emphysematous lesions).

- Chronic restrictive/obstructive diseases.

Endocrine

- Diabetes mellitus.

Other

- Lens opacity.

- Cancer.

Lung cancer and skin cancer are serious long-term concerns in cases of chronic arsenic exposure.

The toxicity of arsine gas is quite different from toxicity of other arsenicals, requiring different emphases in

- the medical history,

- physical examination, and

- patient management.

It is important to recognize that although arsine is an arsenical, it has distinct differences from other arsenicals.

Arsine is a powerful hemolytic poison in both acute and chronic exposures. Massive hemolysis with hematuria and jaundice may persist for several days [Rossman 2007].

The clinical signs of hemolysis may not appear for up to 24 hours after acute exposure, thereby obscuring the relationship between exposure and effect.

Initial symptoms of arsine poisoning may include

- headache,

- nausea,

- abdominal pain, and

- hematuria.

Direct effects on the myocardium may occur, resulting in

- high peaked t-waves,

- conduction disorders,

- various degrees of heart block, and

- asystole [Rossman 2007].

Death is most often due to renal failure from arsenic acid damage, but can also result from cardiac failure [Rossman 2007].

Early clinical diagnosis of arsenic toxicity is often difficult; a key laboratory test in recent exposures is urinary arsenic excretion.

Clinical diagnosis of arsenic intoxication is often difficult because both acute and chronic poisoning present a wide spectrum of signs and symptoms, which are largely dependent upon

- route of exposure,

- chemical form,

- dose, and

- time elapsed since exposure.

In many cases, the patient or person providing the history may suppress information, or the source of exposure may not be apparent. By integrating laboratory results with history and clinical findings, it is often possible to confirm a diagnosis.

Immediately after patient stabilization, laboratory tests should be performed to obtain baseline values, with periodic monitoring as indicated.

Because urinary levels of arsenic may drop rapidly in the first 24-48 hours after acute exposure, a urine specimen for arsenic analysis should be obtained promptly.

Depending on the patient’s clinical state, general tests for biomarkers of effect, specific tests for biomarkers of exposure, and specific biomarkers of effect may be warranted.

- General Tests for Biomarkers of Effect

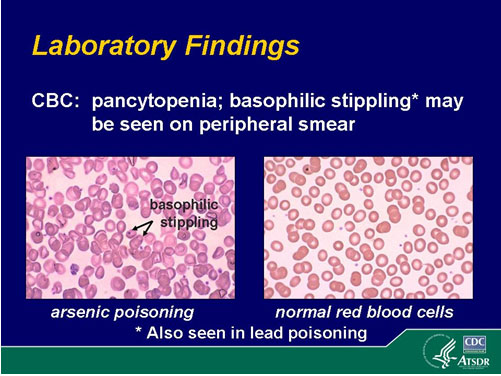

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with peripheral smear.

- BUN and creatinine.

- Liver enzymes.

- Nerve conduction studies (if peripheral neurologic symptoms are present).

- Electrocardiogram.

- Abdominal X-ray.

- Chest X-ray.

- Specific Tests for Biomarkers of Exposure

- The key diagnostic laboratory test for recent exposure is urinary arsenic measurement.

- The best specimen is a 24-hour urine collection for arsenic and creatinine as it more accurately reflects the true amount of arsenic excretion. (Not all labs adjust the arsenic value per gram of creatinine which accounts for the dilution and concentration of the sample).

- Spot urine specimens (also for arsenic and creatinine) can be helpful in an emergency. A spot urine should be sent for arsenic and creatinine. Dividing the arsenic concentration by grams creatinine adjusts for urine dilution or concentration.

- Total arsenic values in excess of 100 micrograms (µg) per liter (L) (µg/L) are considered abnormal [ATSDR 2007].

- However, total arsenic measurement in human urine assesses the combined exposure from all routes of exposure and all species of arsenic.

- Therefore, when total urinary arsenic is measured, it is important to inquire about recent seafood (bivalve mollusks, crustaceans) and seaweed in the diet in the last 48 hours as seafood or seaweed arsenic can significantly increase total urinary arsenic levels (sometimes by several thousands of µg/L after seafood ingestion.) [Kales et al. 2006]

- Where total urinary arsenic level is high and seafood is considered a possible contributor, a request for speciation of arsenic (i.e., analysis of organo-arsenicals or different inorganic species, rather than total) may be a consideration.

- Not all labs that perform arsenic level measurement also perform speciation. If your laboratory does not perform this test, you may wish to consult your local Poison Control Center for this information.

- If speciation is not available, cessation of seafood ingestion with a repeat of the total urinary arsenic test in 2 or 3 days can be done.

- The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2003-2004) measured levels of total arsenic and speciated arsenic in urine of a representative sample of the U.S. population. The data reflect relative background contributions of inorganic and seafood-related arsenic exposures in the U.S. population. Biomonitoring results since the 2015 publication of the Updated Tables, 2015 can be found at: http://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Feb2015.pdf [PDF – 59.7MB] [CDC 2009, Caldwell et al. 2008].

- NHANES 2003-2004 data show that as total urinary arsenic levels increase from <20 to 20-50 micrograms per liter and to >50 µg/L, the percentage of the total urinary arsenic is increasingly due to arsenobetaine (fish arsenic), with median percentages being 62.7% for total urinary arsenic levels >50 µg/L [CDC 2009].

- Some studies suggest that slight health risks may be associated with total urinary levels > 50 µg/L [ACGIH 2001; WHO 2001; Tseng et al. 2005, Valenzuela et al. 2005].

- Conclusions from the NHANES 2003-2004 data indicate that a urine sample of < 20 µg/L is likely to have little contribution from organic arsenic species [CDC 2009].

- For all participants aged > or equal to 6 years, the 95th percentile for total urinary arsenic and the sum of inorganic-related arsenic were 65.4 and 18.9 µg/L respectively [CDC 2009].

- The 95th percentile of the NHANES 2003-2004 subsample for the sum of inorganic arsenic species (18.9 µg/L) is below the ACGIH Biologic Exposure Index (BEI) for workers of 35 µg arsenic per liter (inorganic plus methylated metabolites in urine) measured at end of a work week. (Note that the BEI is not a value for the onset of toxicity, but a screening value based on non-cancer health effects. They were developed for individuals trained in industrial hygiene to use, interpret and apply as applicable.) [ACGIH 2005]

- The sum of the inorganic-related species is an important upper benchmark for the U.S. population as it represents a dose of the more toxic inorganic arsenic most likely incurred from drinking water [Caldwell et al. 2008].

- If 18.9 micrograms is considered an approximate daily exposure, ( 0.27 µg/kg/per day) then about 95% of the adult US population is likely to be below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reference dose [EPA 2001] for inorganic arsenic intake (0.3 µg/kg/per day) [Caldwell et al. 2008.].

- Long after urine levels have returned to baseline, the arsenic content of hair and nails may be the only clue of arsenic exposure.

- However, because the arsenic content of hair and nails may be increased by external contamination, caution must be exercised in using the arsenic content of these specimens to diagnose arsenic intoxication.

- Arsenic blood levels, normally less than 1 µg per deciliter (µg/dL) in nonexposed individuals, are less useful than urinary arsenic measurements in following the clinical course of an acute poisoning case because of the rapid clearance of arsenic from the blood [ATSDR 2007].

- Biomarkers of Effect

- If arsenic toxicity is suspected, several tests can be performed to assess clinical status. If abnormal, these may help to confirm clinical suspicion.

- The CBC can provide evidence of

- arsenic induced anemia,

- leukopenia,

- thrombocytopenia, or

- eosinophilia.

Although basophilic stippling on the peripheral smear is not specific for arsenic poisoning, it is consistent with the diagnosis.

Liver transaminases are frequently elevated in acute and chronic arsenic exposure and can help confirm clinical suspicion.

If arsenic neuropathy is suspected, nerve conduction velocity tests should be performed. Such tests may show a decrease in amplitude initially, as well as slowed conduction.

Skin lesions in patients with chronic arsenic exposure may require biopsy to evaluate for skin cancer.

Some arsenic compounds, particularly those of low solubility, are radio opaque, and if ingested may be visible on an abdominal radiograph.

- Evaluation for arsenic toxicity requires a detailed history, including environmental and occupational exposure history, physical examination, and laboratory testing.

- For recent and chronic exposure, the 24-hour urine collection for arsenic is the most useful laboratory test.

- Organic arsenic from recent seafood ingestion (last 48 hours) may produce a positive urine test for total arsenic.

- Arsenic Speciation testing can be requested, but may not be readily available.

- A repeat 24 hour total urinary arsenic test can be done 48 hours after cessation of seafood consumption.