Triple Testing

About CDC

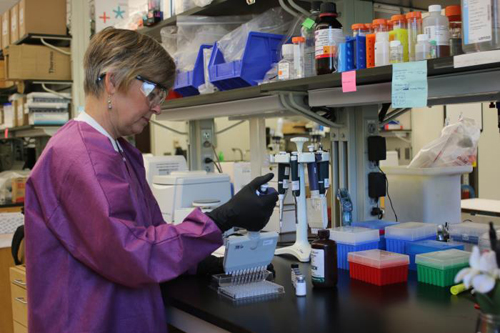

A CDC microbiologist works with one of the tests developed by CDC for the Zika response. In addition to the Trioplex, CDC also developed the Zika MAC-ELISA test, which detects antibodies that the body makes to fight a Zika virus infection.

CDC Works Rapidly to Develop Unprecedented Zika Test

Before Zika virus began spreading in the Americas, CDC’s laboratory team in Puerto Rico was combatting a similar virus: chikungunya. It was 2014, and the mosquito-borne infection was widespread in parts of the Americas, including Puerto Rico.

At that time, CDC’s dengue branch in Puerto Rico tested thousands of chikungunya samples. Like Zika and chikungunya, dengue is primarily spread by mosquitoes and causes symptoms that are similar to the other two diseases. So, during the chikungunya outbreak, the CDC team had to run two separate tests on the samples they received – one for chikungunya and one for dengue.

Because of the high demand for dengue and chikungunya testing, the laboratory’s capacity for testing was cut in half, and it took longer than usual to receive results. After the chikungunya epidemic, the team set a goal: to find a way to more quickly get results.

That is exactly what the team has done with the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay, an unprecedented diagnostic test developed for the Zika outbreak that is able to test for chikungunya, dengue, and Zika. This assay allows laboratories to test for all three diseases at once, without running three different tests to determine which infection the patient might have. Doctors can more quickly diagnose and treat the patient.

When Zika began spreading in Brazil in late 2015, the CDC dengue branch knew the virus was probably going to come to Puerto Rico. The team feared that Zika would spread to thousands of people if it came to Puerto Rico – a prediction that has since come true. CDC’s lab team wanted to be ready with a test that would simplify their work and ensure they could meet their goal.

So, the team immediately began work on a test that would become the Trioplex. The test saves time and resources, a crucial accomplishment as Zika can cause severe birth defects, and more and more people (especially pregnant women) are being tested. By July 2016, the CDC dengue branch in Puerto Rico was receiving about 1,000 samples a week for testing. In fact, about 85% of people with Zika in Puerto Rico have been diagnosed using the Trioplex.

Still, developing the test was far from simple.

First, the team worked nonstop to develop the test in much less time than it would normally take. They worked nights and weekends to createthe Trioplex in 3 months – a task that typically would take 1 or 2 years to complete.

In addition to the swift turnaround, the process of combining three tests into one was tricky. The lab team had to make sure that the tests for Zika, dengue, and chikungunya had the same success rate for correctly identifying each infection — both as separate tests and once they were combined into one test.

Working in a remote location in Puerto Rico, far from CDC headquarters in Atlanta, was challenging at times. Furthermore, it was difficult to perform clinical trials for the test before Zika came to the region, because the team was preparing for something that had not yet arrived. So, they developed the test with Zika virus samples collected from patients in other areas, and, when Zika was first diagnosed in people in Puerto Rico, they were ready to perform trials of the Trioplex.

The next step was submitting the test to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to receive an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), which allowed the test to be used immediately for the Zika outbreak. The process of receiving an EUA is thorough and demanding.

When the EUA was received in March 2016, CDC’s lab team had accomplished their goal of being prepared when Zika hit Puerto Rico with a test that would not only detect Zika virus, but would also determine whether the patient has dengue or chikungunya. The test was put to use during the first month of the Zika outbreak in Puerto Rico, and it has been successfully running for more than 6 months.

Still, the work is far from done and advancements can always be made. The nature of Zika virus presents challenges when it comes to testing. Because Zika virus generally leaves the blood within 1 week and urine within 14 days, it is crucial that people are tested as soon as their symptoms appear. If levels of the virus in the body have greatly declined before the sample is taken for testing, the result is less likely to be positive, even if the patient actually had Zika at one time.

There is a way to detect Zika antibodies (proteins that protect the body from disease and are produced when viruses, like Zika, invade the body). However, that test can be challenging because Zika antibodies are very similar to dengue antibodies. Moving forward, scientists hope to enhance tests, so they can more easily differentiate between Zika and dengue antibodies.

Now, a top priority is to make sure pregnant women who may have been exposed to Zika are tested. Because many people with Zika do not have symptoms, it is critical that healthcare providers proactively test pregnant women in areas where Zika is being spread by mosquitoes. Another priority is to make sure blood collection centers are taking safety measures and screening blood donations for Zika – efforts that already are underway in Puerto Rico and other areas.

As Zika keeps spreading in Puerto Rico and other areas, lab teams continue their important work to support the diagnosis of infection as quickly as possible.