CDC Responds to the 2014 Ebola Outbreak: Chris

About CDC

CDC Disease Detective Chris Edens

In the fall of 2014, as the Ebola epidemic in West Africa continued to grow, Rapid Ebola Preparedness (REP) teams led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spread out to key hospitals across the United States. CDC disease detective William (Chris) Edens, PhD, was a REP team responder.

Their mission: Ensure that hospitals had the necessary staff, training, equipment, and confidence to treat Ebola patients – without becoming patients themselves.

“The hospitals knew this was really important,” says Edens. “It wasn’t like the CDC pushed their way in — it was more like, ‘Please come.’”

During their visits, REP teams helped hospitals find gaps in their Ebola-specific infection control plans. REP teams were made up of four to 10 professionals with a wide range of expertise. Team members came from various government agencies and professional infection-control societies.

“They were really interdisciplinary teams, pulled mainly from federal departments, state agencies, and professional societies,” Edens says. “And the hospitals were really glad to see us. They knew this was really important, and they wanted to get everything out of our visit they could.”

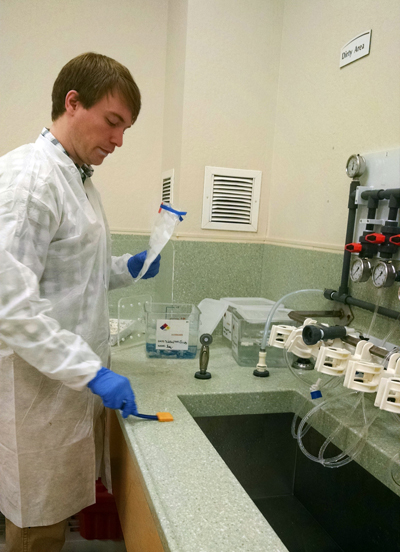

Chris Edens working on dialysis investigation

Edens’ First REP Team Deployment

On his first assignment, Edens’ team was ushered into the main conference room of a major hospital.

“It was the most people in suits I’ve ever seen in my life sitting around the largest conference table I have ever seen,” he recalls. “There were people from county health services all over the state, the state health secretary, all of the hospital’s senior staff, and then us.”

The team quickly went to work. Edens worked with hospital staff on the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Later, hospital staff participated in an extremely realistic exercise in which an actor posed as an Ebola patient.

“They went full out. It was very impressive. The ‘patient’ faked all the symptoms of Ebola,” Edens said. “All the nurses were in full PPE. Then the ‘patient’ had simulated vomiting, and just doused the nurses with a fluid containing a material that shines brightly under a black light. I don’t think the nurses knew it was coming – but when they took off their PPE they were spot clean.”

Not Just Ebola

Edens’ passion for infection prevention predates his CDC work. While earning his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering from Georgia Tech, he helped develop a new way to deliver the polio and measles vaccines. The vaccine patch (a small adhesive containing vaccine-filled microneedles that can be applied without medical supervision) already had been created for other diseases such as flu. Edens worked on adapting the device for polio and measles—work that may one day contribute to the eradication of these diseases.

Edens’ first CDC assignment was to find out what was causing a disease outbreak among patients at a California dialysis clinic. (It turned out to be a relatively rare bug called Burkholderia cepacia.) More recently he’s been analyzing data on central line-associated bloodstream infections to see whether those in general wards differ from those in intensive care units.

He’s still a scientist engineer, but now that he’s been a disease detective –in CDC lingo, an Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officer — Edens doesn’t want to go back to academia.

“I would like to stay at CDC and continue working in public health after I finish my two years in EIS,” he says.