Ebola Report: Communicating and Educating

About CDC

‹View Table of Contents

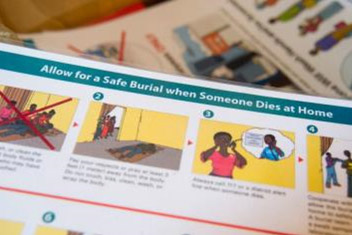

A family under voluntary quarantine in the Kaffu Bullom community of Port Loko, Sierra Leone, looks on as Soriba Suma, a CDC Health Promotion Team member, uses pictures to teach them about Ebola and safe practices.

n an emergency response, communication is often the first line of defense. Fighting disease becomes less stressful when communities understand what they can do, when journalists report accurate information quickly, and when officials know how to communicate effectively. During a disease outbreak, communication strategies provide the essential bridge between science and the public— creating audience-tailored products, spreading accurate information through the best channels, fighting rumors and stigma, and ensuring the response respects a community’s needs.

During a large-scale epidemic like Ebola, scientists aren’t the only experts needed to help stem the spread of disease. CDC also sends teams of experts in communication, education, anthropology, and behavioral science to help communities with low technology access get the information they need to protect themselves—through radio, posters and billboards, and face-to-face visits.

“It was clear to me that Ebola had changed everyday life for Liberians. Hugs and handshakes, common greetings in Liberia, were too risky because of Ebola. Soccer teams wouldn’t meet for practice. Fresh fruits and vegetables weren’t being brought into Liberia from neighboring countries. The efforts to confine the virus also confined so many aspects of everyday life.”

– Karlyn Beer, Ebola responder, Liberia

![“ Ebola is real: Let’s stop the sprea[d] of Ebola.” This banner was displayed on the vehicle of the zonal head for the Kings Gray community near ELWA hospital in Monrovia, Liberia.](./communicating-educating_html_files/educational-messages.jpg)

“Ebola is real: Let’s stop the sprea[d] of Ebola.” This banner was displayed on the vehicle of the zonal head for the Kings Gray community near ELWA hospital in Monrovia, Liberia.

Stories from the Field

Educational messages on Ebola are delivered in unique ways in Liberia. Here, a mural shows symptoms of Ebola.

Ebola talk was everywhere. At church, where parishioners heard sermons about communicable diseases, they also heard about Ebola. Talk was on the radio and music television, where performers sang songs about the deadly virus. It was visible outside Ebola treatment units where patients were sometimes turned away because of a lack of beds.

Erik Reaves, a CDC responder deployed to Liberia, says many of his Liberian colleagues had family members or friends who had died or were sick, and at times they would break down and cry. “They’re just trying to do what they can to keep pushing forward and help the response, but it was taking an emotional toll on them,” he said.

Erik and his team worked with local health officers to identify their technical capabilities, and evaluated their ability to respond to and monitor cases. He helped them get ready to transition from written records to tablets and smartphones, a program funded by the CDC Foundation to support timelier reporting of cases.

Guinea Red Cross volunteers travel door-to-door sharing information about Ebola.

When Monique Tuyisenge-Onyegbula arrived in West Africa, she brought more than the standard trunkful of CDC-issued gear and personal protective equipment.

“What I brought was my technical skills and my understanding of the culture and customs,” said Monique, who was born in Michigan but raised in Rwanda. To add to that unique mix of cultures, she is now married to a Nigerian. She has lived and worked in several African nations. In addition to English, she speaks Kinyarwanda (common to Rwanda and Burundi), Swahili, and French.

Monique is quick to point out there is no single “African culture”—it’s a big continent of many nations and people.

“But we do share things in common, such as the proper way to address elders or our difficulty remembering to avoid touching others during an Ebola outbreak—touching is a big thing in Africa,” she said. “I don’t have to think about these things because I am an African, an insider. I am received not as ‘they are coming to help us,’ but as ‘we are helping ourselves.’”

Monique said that is what is important: working with youth, local people, and community leaders to spread the message. “We from CDC can’t reach all these people, so must rely on the volunteers in the communities to spread the awareness. We train as many as we can, giving anyone and everyone the skill and knowledge to educate others on preventive measures.”

Materials developed at CDC headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, are being used in Sierra Leone to educate people in villages.

In the Kroo Bay Slum in Sierra Leone, life expectancy was 35 years—and then Ebola hit. In that neighborhood, Nicole Hawk, a CDC communication expert, saw what she was up against.

“People are living on top of each other, lacking basic sanitation and medical care. It was really eye-opening. It’s vital that we do what we can to stop this outbreak,” she said.

For a month, Nicole helped craft and distribute Ebola-prevention messages for the general population in Freetown, Sierra Leone. During her deployment, the team began to shift its messaging from the basic “Ebola is real” to steps people can take to protect themselves and their families from the virus.

The visit to the slum highlighted how hard those messages are to follow.

“Washing your hands isn’t easy when you don’t have regular access to clean water. Quarantining someone in a separate room isn’t easy when an entire family lives in one room, and getting help isn’t easy when ambulances can’t get in because of a lack of roads,” Nicole said. “It really made me realize just how critical it is that we be on the ground trying to stop the virus.”

Nicole said her work has never been so important or gratifying. “I felt like the work we were doing was having a direct impact on saving lives.”

A river dividing Guinea and Liberia shows how easily people can travel from one country to the other.

When Kelsey Mirkovic deployed to Guinea, she quickly saw one of the reasons Ebola had managed to spread so easily through three West African nations. Families often live on both sides of the shallow, narrow river that divides Guinea from Sierra Leone and Liberia. People can easily shout across the muddy stream, and boatmen readily ferry travelers from one nation to the next. If people can cross freely, so can Ebola.

Armed with her “intermediate” French, Kelsey visited area villages. Although the nation’s official language was French, sometimes only one person in a village might speak it, so she worked with that person to translate important health messages into the local language. In this manner, she worked to gain the confidence of village leaders and to train community health workers to spread the word about how to avoid getting—and stop spreading—Ebola.

Kelsey’s team trained them to follow up with anyone who was exposed to patients with Ebola, checking on them every day for three weeks. Every day, except Sunday, the workers would report their findings to a supervisor.

“One day, the community workers reported that a person with Ebola symptoms had refused to go to into isolation at the treatment center,” Kelsey says. “It was a Monday, so the report was two days old. Worried, I met with the village chief, who pressured the person to go to the center.”

Out of that one meeting, many lives were saved. The grateful village chief presented Kelsey with a symbolic gift of cocoa pods and a coffee plant. For her, the gift symbolized not how much she gave, but how much she received.