Influenza Outbreak in Laos Hill Tribes Halted with Quick Response and Regional Support

Seasonal influenza viruses circulate globally in people and are estimated to cause between 291,000 and 646,000 deaths worldwide, annually. Recently, indigenous hill tribes living in a remote northern province of Laos experienced a devastating outbreak of seasonal influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 which caused 16 deaths in December and January. The high flu-related mortality sparked attention and local public health partners trained with U.S. CDC support responded quickly to the outbreak in Phongsaly Province by rapidly delivering influenza antiviral drugs for treatment, providing health education and hygiene/sanitization interventions to slow the spread of disease, and funneling influenza vaccine to the crisis area for longer-term prevention of flu among the hill tribes. The last outbreak-related death occurred during the early days of the response; the other fifteen had all occurred previously.

Health care providers administered antiviral treatment and influenza vaccine to affected villages. Phongaly Province, Laos. 2019

CDC’s regional influenza program in Thailand worked with Thailand’s ministry of public health to deliver emergency supplies of the influenza antiviral drug oseltamivir from Thailand’s government pharmaceutical office to Laos in less than 24 hours. The team also redirected flu vaccine from Laos’s ongoing influenza vaccination campaign to reach the indigenous hill tribes, resulting in more than 2,200 people being vaccinated and achieving a 74 percent vaccination rate (People already showing flu symptoms were not vaccinated, and, as the redirected vaccine was approved for use in people 5 years and older, children younger than 5 were not vaccinated either.) Two health education sessions were provided to each of the nine affected villages. Education included how to cover coughs and sneezes, wash hands, stay home when sick, and maintain cleanliness when eating, drinking and living. Educational posters on the transmission of influenza and other infectious diseases also were provided, along with soap for affected families.

Based on previous outbreak responses, it could have taken two weeks or more to obtain a stockpile of oseltamivir from outside of the country. Such delays can allow the virus to take even more lives in a susceptible community, and possibly spread to neighboring communities. In this case, no new deaths have been reported, and the epidemic curve of this outbreak has shown a decline.

What made this outbreak of A(H1N1) so deadly is still under investigation. However rural populations such as these are often not vaccinated against seasonal influenza and usually have little access to health care. Many people are also malnourished and may have unmanaged underlying conditions that put them at high risk of complications from influenza.

Health care providers administered antiviral treatment and influenza vaccine to affected villages. Phongaly Province, Laos. 2019

The rapidity of this successful response points to the enduring public health value of CDC’s ongoing partnerships with the Laos Ministry of Health and Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health. Laos is a relatively small country in Southeast Asia with roughly 6 million people, some of whom live in semi-isolated villages connected with others only by rutted mountain paths that are often impassable with regular vehicles. While some villages have electricity and cell phones, others do not, and some rural populations do not have access to trained health care. The majority of people in Laos derive at least part of their income from raising livestock, making chickens, pigs, ducks and other waterfowl central to their everyday lives. Often these animals live intermingled and in very close proximity to their human owners, raising the probability of influenza viruses spreading between animals and people, a dynamic which has sometimes led to the “birth” of novel influenza viruses with pandemic potential. It’s in this context that U.S. CDC has partnered with Laos through cooperative agreements over the past few years, vastly raising the country’s ability to respond rapidly to seasonal, avian, and novel influenza virus outbreaks; and to immunize their people annually against seasonal influenza. Due to this relationship, Laos was the first lower-middle income country to establish its own sustainable influenza vaccination program.

While CDC has a single staff person based in Laos, on a global scale CDC is doing what local responders are rarely able to do. As research findings mount with regard to the best ways for rural communities to respond to outbreaks like this one, CDC works with country officials to translate those findings into actionable steps and trainings each province can use to arm their local responders in the fight against influenza. By working with partners to respond efficiently on the front lines, CDC’s investments in public health protect our home populations against emerging threats, while at the same time providing benefits to those that we work with globally.

Alternative Text for 508 Compliance:

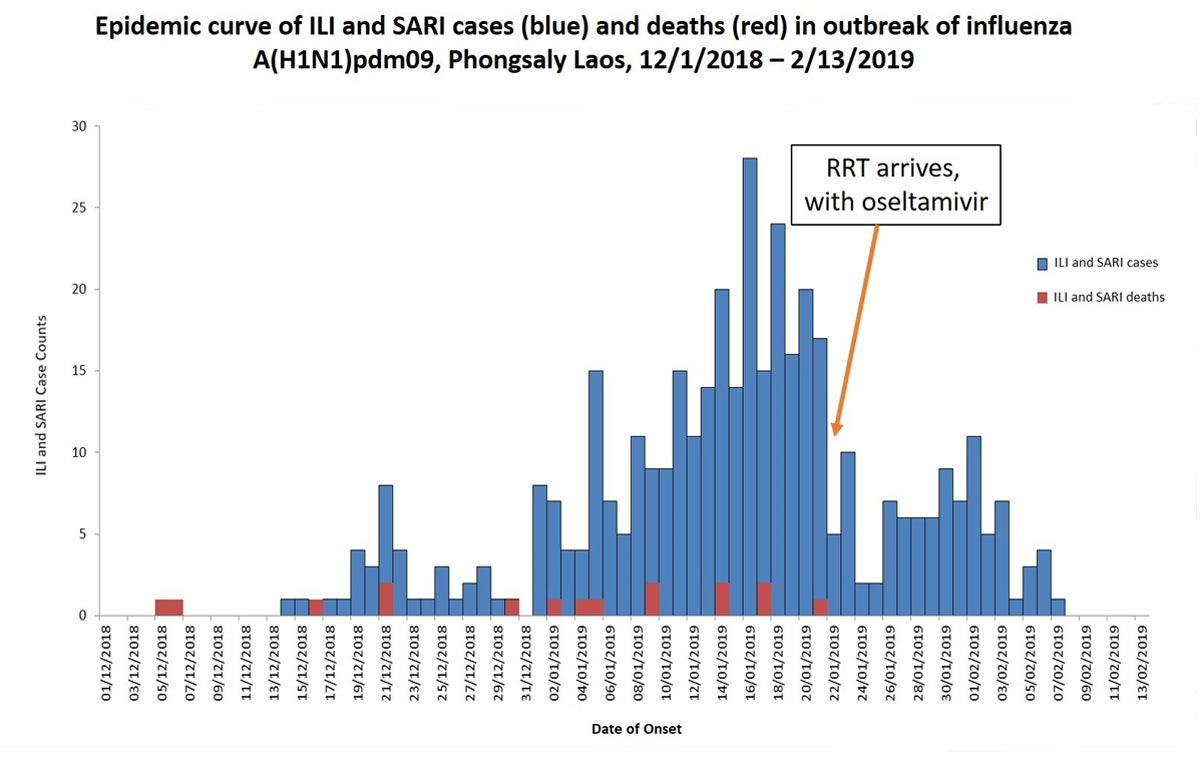

This is a bar chart showing the epidemic curve of influenza-like illness – ILI – and deaths in the outbreak of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 that took place in Phongsaly, Laos, The start of this bar chart is December 1st 2018 and the end of it is February 13th, 2019.

Blue is used to represent ILI and Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI) cases

Red is used to represent ILI and SARI deaths

The X Axis lists the date of onset, between December 1st and February 13th.

The Y Axis displays the number of cases that occurred.

In terms of deaths, the chart shows that deaths were reported on each of these dates: December 5 (1), December 6 (1), December 16 (1), December 22 (2), December 30 (1), January 1 (1), January 4 (1), January 5 (1), January 9 (2), January 14 (2), January 17 (2), and January 21 (1). In total, 16 deaths occurred.

The chart also shows that ILI and SARI cases first started to be reported on December 14th with a small spike on December 21, and then a drop, and then increasingly large spikes starting January 2 and peaking on January 16th. After January 16, cases began to decrease, although there was another smaller wave of illness that peaked on February 1, 2019. The last illness was reported on February 7, 2019.

The chart also shows when the Rapid Response Team arrived with oseltamivir, which was on January 22, 2019.