Number of Swine Origin H3 Infections in Pennsylvania Rises to Three

September 6, 2011 — CDC laboratory testing has confirmed two additional cases of human infection with swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses in children in Pennsylvania. These additional two cases bring the total number of confirmed cases of human infection with swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses from the Pennsylvania investigation to three. According to the Pennsylvania Department of Health, all three of the children confirmed with swine origin influenza A (H3) influenza infection reportedly attended the Washington County Agricultural Fair the week of August 13-20, 2011, where swine were exhibited.

The first case of human infection with swine origin influenza A (H3) in Pennsylvania was reported in an MMWR early release issued on Friday, September 2, 2011 and occurred in a girl younger than 5 years. The two cases confirmed over the weekend also occurred in girls, both younger than 10 years. All three of the patients were in the area where swine were exhibited and one had direct contact with swine.

Like humans, pigs can become infected with and spread their own influenza viruses. The symptoms of swine flu in pigs are very similar to the symptoms humans get from human seasonal flu illness and can include coughing, lack of appetite, runny nose and lethargy. Not only do pigs become infected and spread swine influenza viruses, but they can be infected with both human and avian influenza viruses. Though rare, humans also can be infected with swine influenza viruses.

“It′s pretty rare to see human infections with swine flu viruses. CDC gets reports of about 5 cases of human infections with swine flu viruses each year,” says Lyn Finelli, Chief Outbreak Investigator for CDC′s Influenza Division. “Most of the time, these cases occur after close contact with pigs and seldom spread onward from the first person infected.” There have been rare cases where human-to-human transmission may have occurred, most recently in Indiana in a case also reported in the September 2, 2011 MMWR early release. “The hallmark of influenza viruses is their ability to change,” cautions Mike Shaw, the Influenza Division′s Associate Director for Laboratory Science. “That is why we watch these types of situations closely, to make sure that the virus hasn′t changed to allow efficient and sustained human-to-human transmission.”

The investigation in Pennsylvania is continuing in order to determine if more people are sick or if there is ongoing spread of this virus in the community. A number of CDC staff are in Pennsylvania assisting the Department of Health in the investigation. “Fortunately,” Finelli says, “it does not look like there is current spread in the community and so far, illness associated with these viruses has not been especially severe. Two of the patients are fully recovered and the third is recovering.”

The viruses isolated in Pennsylvania are a little different from previously seen swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses in that all have acquired a gene from the human 2009 H1N1 viruses. This likely occurred as a result of swine being co-infected with the swine origin influenza A (H3) virus and the human 2009 H1N1 virus. The swine origin influenza A (H3) virus acquired one gene from the human 2009 H1N1 virus, the “M” gene. This is the first time this combination of genes has been seen in swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses.

Swine likely became infected with human influenza A H3 viruses in the 1990s. Since then swine influenza A (H3) viruses split off from human influenza A (H3) viruses and have changed to the point where swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses are very different from human influenza A (H3) viruses that circulate routinely each season now. “The seasonal influenza vaccine, which protects against three human seasonal flu viruses including one H3N2 virus, would not protect against infection with these swine origin viruses,” Finelli says. The seasonal vaccine will protect against the three human seasonal flu viruses that research indicates are most likely to circulate this fall.

While there is not a vaccine to protect humans against these swine origin influenza A (H3) viruses, there are two FDA-cleared drugs that can treat infection with these viruses. The antiviral drugs oseltamivir and zanamivir – which are used to treat infection with human seasonal viruses — also show activity against these viruses. “That is one of the messages we wanted to get out to clinicians, “Finelli says. “If they see influenza like illness and suspect influenza and there is a history of swine exposure, clinicians should consider treating their patients with influenza antiviral medications, even before they get a positive influenza test result. This is especially true if there is little seasonal influenza activity, which is the case in most of the United States at this time.”

For more information about swine influenza, visit the CDC swine flu website.

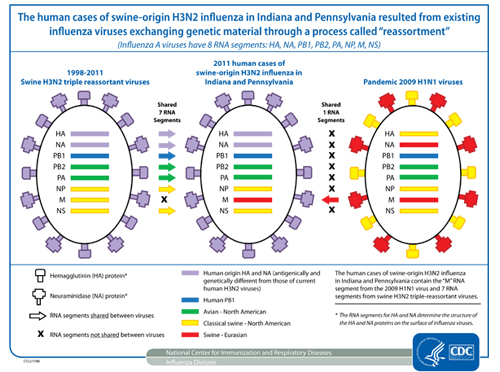

The cases of human infection with swine–origin H3N2 influenza resulted from existing influenza viruses exchanging genetic material through a process called “reassortment.” Reassortment typically occurs when a host – animal or human – becomes infected with two or more different influenza viruses at the same time. This allows the influenza viruses to mix and exchange genetic information with each other, which in turn, can result in the emergence of new influenza viruses. Because pigs can be infected with and spread influenza viruses from birds, pigs and humans, they can represent a source for influenza virus reassortment to occur. This is particularly true in environments where humans, pigs and birds come into close contact with one another, such as farms.

The above graphic depicts how the human cases of swine-origin H3N2 influenza virus reported in Indiana and Pennsylvania resulted from the reassortment of two different influenza viruses. The image on this page shows three influenza viruses placed side by side, with eight color-coded RNA segments inside of each virus. Note: All influenza viruses contain 8 RNA segments. These RNA segments are labeled HA (hemagglutinin), NA (neuraminidase), PB1, PB2, PA, NP, M and NS.

The virus in the center of the picture represents the human cases of swine-origin H3N2 influenza in Indiana and Pennsylvania. Seven of these viruses’ eight RNA segments are derived from influenza viruses that commonly circulate in pigs. The virus on the left of the diagram, labeled “1998-2011 swine H3N2 triple reassortant viruses,” represents these swine influenza viruses. These swine viruses are called triple reassortant viruses because they contain genetic material from humans, pigs and birds.

Arrows between the left virus and center virus in the diagram show which seven of the eight RNA segments found in H3N2 triple-reassortant swine influenza viruses (represented by the left virus) are shared with the human cases of swine-origin H3N2 reported in Indiana and Pennsylvania (center virus).

The virus image on the right in the diagram represents the 2009 H1N1 virus that caused the pandemic which began in the spring of 2009. The human cases of swine–origin H3N2 influenza found in Indiana and Pennsylvania share one RNA segment, the M segment, with this 2009 H1N1 virus, as reflected by the red arrow placed next to the M segment between the right and center viruses in the diagram. No other RNA segments are shared between these two viruses, as denoted by the X’s next to each RNA segment between the right and center viruses in the diagram.

A key at the bottom of the diagram explains the color-coding scheme for each of the RNA segments. Purple-coded RNA segments represent human origin HA (hemagglutinin) and NA (neuraminidase), which are genetically and antigenically different from those of current human H3N2 viruses. The center virus and left virus in the diagram contain purple-colored, HA and NA segments. Blue–coded RNA segments represent PB1 segments that came from humans. All three viruses have PB1 segments that came from humans. Green-coded RNA segments represent segments that came from birds in North America. All three viruses have green PB2 and PA segments. Yellow–coded RNA segments represent segments that came from classical North American swine. The NP and NS segments from all three viruses are yellow. The M segment within the left virus in the diagram is also yellow. And lastly, red-coded RNA segments represent segments that came from Eurasian swine. The M segment in both the right virus and the center virus in the diagram are red.