Division of Global Health Protection (DGHP)

Nigerian CDC-trained disease detectives administer questionnaires to community members to collect data about a pertussis outbreak.

Photo Courtesy: Visa Tyakaray

2017 DGHP SNAPSHOT

- Trained more than 2,100 new disease detectives, who are critical to countries’ abilities to quickly find and stop disease outbreaks, through DGHP’s Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP).

- Mobilized “rapid response teams” of CDC experts over 240 times to support emergency response in 50+ countries across the globe.

- Provided technical expertise for 25 of 39 WHO Joint External Evaluations (JEEs) that offer clear and independent assessments of each nation’s health security capabilities and identify critical actions for improvement.

- Monitored and stopped dangerous health threats, tracking nearly 340 events of public health importance through surveillance systems that operate 24/7.

- Conducted new research to look at the dynamics of transmission and reservoirs for Zika virus in 4,726 amphibians, birds, reptiles, and mammals and 27,216 mosquitos in Peru, Brazil, and Colombia.

Year in Review

The Division of Global Health Protection (DGHP) brings science and expertise to stop potential pandemics at the source – eliminating outbreaks abroad so CDC does not have to fight them here at home. The division’s scientific and technical experts work closely with partners to strengthen vital prevention, detection, and emergency response capabilities, even in the most challenging parts of the world. From Ebola to Zika and beyond, the division plays a critical role in supporting CDC’s mission to protect the health, safety, and security of Americans.

Monitoring Threats 24/7

To detect outbreaks across the globe, DGHP has programs that work 24/7 to collect information about events that could be serious risks to public health. Scientific and technical experts in Atlanta closely monitored 30–40 threats per day worldwide and tracked nearly 340 events of public health importance in 2017.

To help countries quickly identify and respond to diseases within their region, DGHP supported ten disease detection centers around the world to help detect emerging and reemerging pathogens so that outbreaks can be stopped at their source. CDC subject matter experts within these centers supported over 150 outbreak responses and provided technical assistance to more than 40 countries.

Laboratorians in Thailand trained in the safe handling of pathogens.

| Global Disease Detection Operations Center | 337 unique outbreaks tracked |

|---|---|

| Global Disease Detection Centers | 198 outbreak responses supported |

| Field Epidemiology Training Program | 616 outbreaks investigated by fellows |

| Global Rapid Response Team | 6,370 person-days of deployments for response |

Faster, Smarter Response

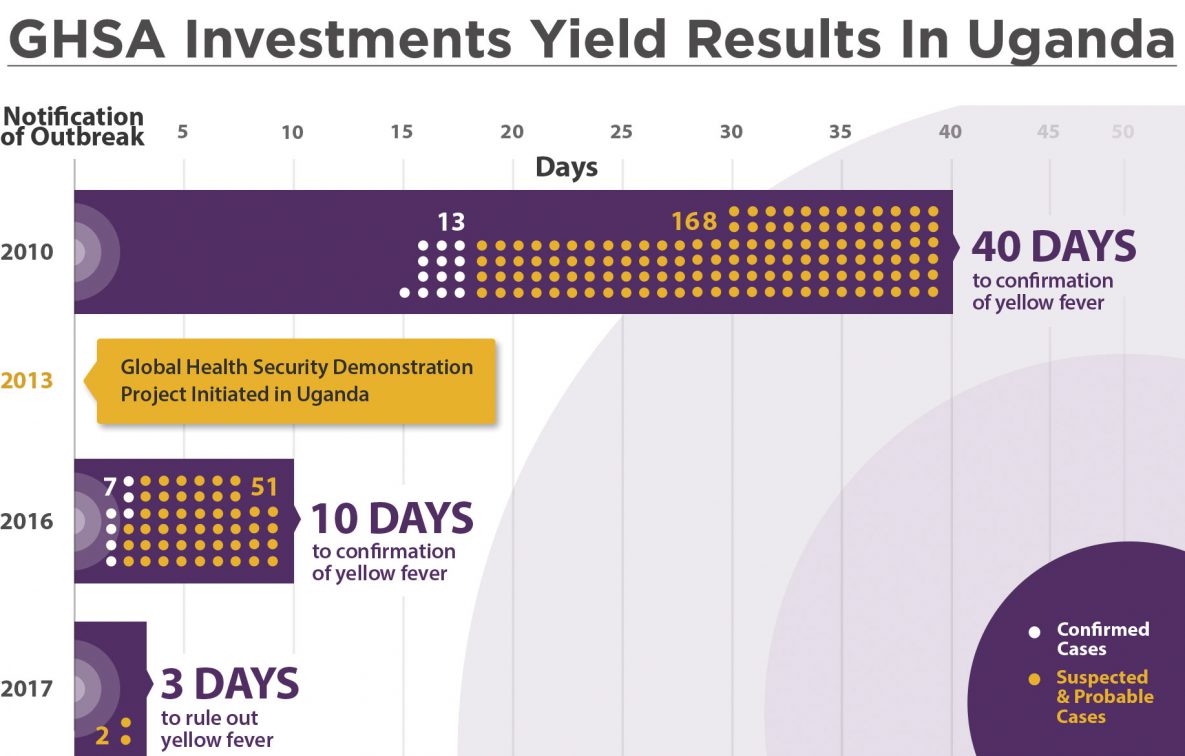

When every second counts, a country’s ability to respond can mean the difference between a local outbreak and a global pandemic. In 2017, better emergency response capabilities in CDC partner countries led to faster containment of deadly outbreaks. From involving communities in reporting illness, to finding better ways to get laboratory samples safely delivered and accurately tested, to more efficient management of resources and people, DGHP helped reduce emergency response times in partner countries like Uganda and Cameroon from weeks to days – or even hours.

Responding to global outbreaks, natural disasters, and other emergencies when and where they occur is critical to stopping health threats before they reach U.S. shores. CDC’s Global Rapid Response Team (GRRT) is an agency-wide resource managed by DGHP with over 400 CDC experts ready to deploy in response to a public health emergency anywhere in the world at any given time. In 2017, the GRRT mobilized staff over 240 times to more than 50 countries to support outbreak response and to provide public health expertise, logging over 6,370 person-days of deployments in response to emergencies including Lassa fever in Nigeria, plague in Madagascar, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

To eliminate outbreaks at the source, DGHP trains “boots on the ground” disease detectives in other countries through the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP). This year, CDC-trained disease detectives investigated more than 570 threats across the globe. To expand detection and response capabilities at the local level, the FETP-Frontline program trained more than 1,800 new frontline responders who were among the first on the scene to identify and contain outbreaks of international concern like yellow fever, Ebola, and Marburg virus.

Strengthening Global Health Security

CDC advances global health security by building public health systems that work hand-in-hand to help countries prevent, detect, and respond to public health threats. DGHP leads the agency’s efforts to implement the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) in close partnership with other CDC divisions and centers, U.S. agencies, and global partners.

As of 2017, DGHP and its partners noted more than 675 significant achievements across CDC’s global health security partner countries, including expanded surveillance systems, new diagnostic equipment and capabilities, and more and better-trained frontline responders. Putting the right systems and people in place across the globe is our country’s best chance for stopping a future pandemic or bioterrorist event and for protecting our well-being.

CDC also works to strengthen global health security through prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. NCDs (including cardiovascular disease and hypertension, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory disease) place additional strain on already fragile health systems and undermine their ability to handle large outbreaks. Building upon lessons learned from CDC’s communicable disease efforts, DGHP’s global NCD programs support critical partnerships, create healthier populations, and build more robust health systems that can help recognize potential epidemics early.

To bolster public health capacity at the national level, CDC is supporting 25 countries in developing or strengthening their national public health institutes (NPHIs). Like CDC in the United States, NPHIs serve as homes for countries’ public health systems and expertise. In 2017, CDC worked with partners to fully launch the NPHI Staged Development Tool that countries are using to define critical next steps for protection.

Global health security work is closely connected to U.S. economic security; health protection helps ensure stable markets and steady demand for U.S. goods and services. For example, a hypothetical model shows that an outbreak in Asia that spreads to 9 countries could put more than 1.6 million export-based U.S. jobs at risk, even if it never reaches American shores. Preventing and responding to outbreaks abroad protects these jobs in sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and natural resource extraction.

Emergency Public Health Epidemiologist Emilio Dirlikov labels dengue samples in Burkina Faso in 2017 Photo credit : Anselme Sanou (DGHP/Burkina Faso country office).

Identifying Gaps and Setting Future Priorities

Finding and addressing gaps in the world’s health systems is critical to protecting America from epidemics. In 2017, DGHP worked closely with other CDC colleagues, the World Health Organization (WHO), and partners from other international organizations to help countries identify the most urgent needs within their health systems through the WHO Joint External Evaluation (JEE) process. Based on the requirements of the International Health Regulations, the JEE is a voluntary, multisectoral, and comprehensive process to assess a country’s capacity to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to public health risks. As of December 2017, nearly 70 countries had completed JEEs, with CDC experts participating in over 60% of these.

CDC worked closely with partners in 2017 to conduct large-scale exercises that challenged countries’ abilities to efficiently and effectively coordinate an emergency response. These exercises tested the performance of public health emergency operations centers, real-time information sharing, laboratory capabilities, exchange among national public health institutes, and other critical systems that identify and contain disease outbreaks.

- Bell E, Tappero JW, Ijaz K, et al. Joint External Evaluation—Development and Scale-Up of Global Multisectoral Health Capacity Evaluation Process. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi:10.3201/eid2313.170949.

- Boyd AT, Cookson ST, Anderson M, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Response to Humanitarian Emergencies, 2007–2016. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi:10.3201/ eid2313.170473.

- Cassell CH, Bambery Z, Roy K, et al. Relevance of Global Health Security to the US Export Economy. Health Security. 2017; 15(6):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2017.0051.

- Christian KA, Iuliano AD, Uyeki TM, et al. What We Are Watching—Top Global Infectious Disease Threats, 2013-2016: an Update from CDC’s Global Disease Detection Operations Center. Health Security. 2017; 15 (5):453-462. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2017.0004.

- Doedeh J, Frimpong JA, Yealue KD II, et al. Rapid Field Response to a Cluster of Illnesses and Deaths — Sinoe County, Liberia, April– May, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2017; 66:1140–1143. doi: http://dx.doi.ExternalExternal org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6642a4.

- Fitzmaurice AG, Mahar M, Moriarty LF, et al. Contributions of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Implementing the Global Health Security Agenda in 17 Partner Countries. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi: 10.3201/eid2313.170898.

- Jones DS, Dicker RC, Fontaine RE, et al. Building Global Epidemiology and Response Capacity with Field Epidemiology Training Programs. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi:10.3201/eid2313.170509.

- Rao CY, Goryoka GW, Henao OL, et al. Global Disease Detection—Achievements in Applied Public Health Research, Capacity Building, and Public Health Diplomacy, 2001–2016. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi:10.3201/ eid2313.170859.

- Tappero JW, Cassell CH, Bunnell R, et al. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Its Partners’ Contributions to Global Health Security. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017; 23(13). doi:10.3201/eid2313.170946.

DGHP works to protect the health and safety of Americans and people around the world. We:

- Monitor public health threats 24/7, lead CDC’s Global Rapid Response Team, conduct disease surveillance, and build emergency and laboratory systems to better respond to crises.

- Work with countries to prevent, detect, and respond to global health threats and address chronic or systemic gaps in local capabilities.

- Provide unique technical and leadership expertise that is underpinned by science and evidence and is far reaching, not limited to a single pathogen.

- Protect Americans by responding immediately to public health threats and by helping countries and partners contain emerging threats at the source.

Strengthening health security: Building on 2017 accomplishments, it is critical that CDC remain vigilant and continue to address major health risks, recognizing that weak health systems in any country directly impact the health and security of communities in the United States. Global health protection requires focus beyond one country, one issue, or one pathogen, as well as strong collaboration with internal and external partners around the globe.

National Action Plans: DGHP will continue to provide technical expertise and support for countries as they develop National Action Plans for Health Security. These plans clearly articulate the steps necessary to address the gaps identified through Joint External Evaluations and help countries direct domestic and external resources to their most critical gaps in health security.