Preparedness pays off with quick response time

Health seeking behavior near Mpwonde and Lake Edward, Uganda

Ugandans knew they had to get ready for the worst when neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) reported a new Ebola outbreak on August 1, 2018. Uganda shares more than 550 miles of border with DRC and sees thousands of people move between the two countries daily.

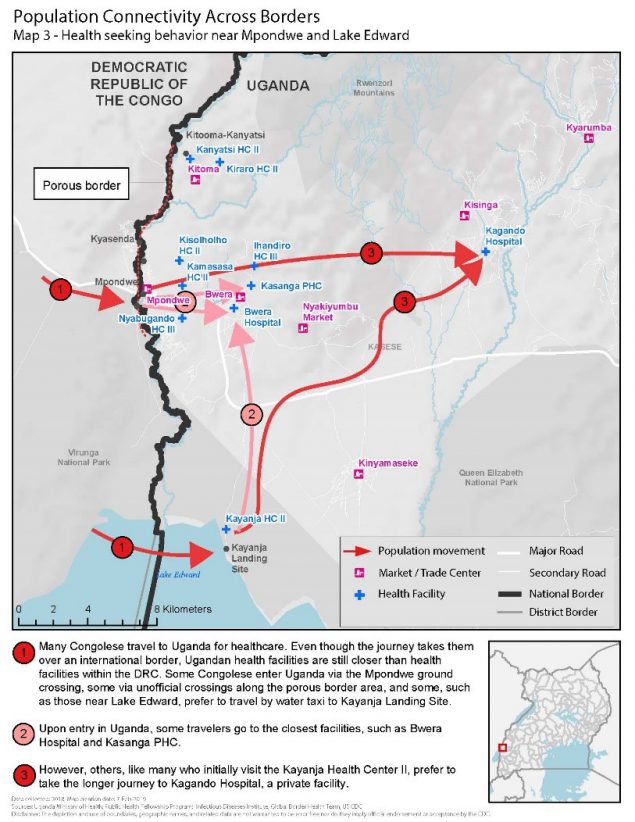

Understanding mobility patterns and connectivity between communities can inform preparedness and response efforts by identifying points of interest visited and routes traveled. Uganda’s Ministry of Health (MOH) activated the Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (PHEOC) and began preparedness activities. They wanted to be ready to rapidly detect, respond and stop further spread of Ebola if a case crossed the border. Since 2013, CDC-supported global health security investments and efforts in Uganda have dramatically helped the country reduce the time it takes to detect and respond to outbreaks. CDC has been supporting the MOH and its implementing partner, the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), to map routes traveled between DRC and Uganda, and points of interest within Uganda visited by Congolese, including health care facilities like Kagando Hospital.

Within the first week of the response, the MOH deployed a 14-person border health team to conduct point of entry assessments and characterize cross-border population movement in priority districts. The team used an adapted version of a CDC toolkit to hold community engagement activities to understand the behavior of Congolese seeking health care in Uganda. Results showed that Congolese would travel further into Uganda to reach Kagando Hospital rather than access closer government facilities. This information helped the District Task Force prioritized Kagando Hospital for evaluation and preparedness interventions. Similarly, local and national MOH level offices adjusted border health and surveillance preparedness initiatives to target the locations with the highest connectivity to the outbreak area in DRC. The MOH and IDI continue to map population movement along the shared borders with DRC and Rwanda. The results are used to inform preparedness interventions, including health care worker vaccinations, targeted community surveillance training, and strengthened infection and prevention control measures.

With support from CDC and other Global Health Security partners, Uganda is better prepared to respond to outbreaks at the source. This preparedness paid off when several travel-related Ebola cases were identified and quickly contained in Uganda in June 2019.

CDC Director Robert Redfield,the Minister of State for Health Sarah Opendi, and the US Ambassador to Uganda, Deborah Malac learn about Uganda Preparedness activities in 2018. Photo credit: Irene Nabusoba

On April 11, 2019, the Uganda MOH, CDC, and other partners held a nationwide Ebola outbreak simulation exercise. The three scenarios were: arrival of an ill traveler at Entebbe International Airport, detection of an ill person referred to Kagando Hospital in Kasese District, and identification of an ill traveler at a border crossing in Kasese. All three scenarios involved the PHEOC in the capital, Kampala.

Stopping Ebola requires early identification of cases, effective isolation of people ill with Ebola, and contact tracing of people exposed to Ebola patients so they can be vaccinated and isolated if they develop symptoms. The exercise evaluated the operational capabilities and identified strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement of Uganda’s emergency management systems at the border, in communities, health facilities, districts, and at the national level. Key capacities assessed included: Ebola alert management systems at key points of entry; isolation, transportation, and management of people with a suspected case of Ebola; laboratory sample collection, packaging, and dispatch; and initial management of people confirmed to have Ebola. The exercise also looked at community engagement in case of an Ebola event, knowledge and skills of village health teams, capacity of health facilities to handle cases, and general logistics and coordination at the district and national levels.

“Our aim with the simulation was to build full capabilities for full-fledged, real-time deployment and response. This made a world of a difference when Ebola crossed the border,” said CDC Uganda Division of Global Health Protection program director, Jaco Homsy.

Responders wearing appropriate personal protective equipment during the simulation exercise. Photo credit: Irene Nabusoba

Two months after the simulation exercise, on June 11, 2019, the Uganda Minister of Health confirmed the first case of Ebola in the country—introduced by travelers from neighboring DRC. As it turned out, the simulation at Kagando Hospital in Kasese District helped medical staff quickly recognize Ebola symptoms in a patient who arrived at their hospital. A blood sample from the patient tested positive at a local laboratory. The MOH immediately formed a rapid response team that works with district health teams and local leaders to investigate and respond to other suspected Ebola cases. The team included 16 Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) fellows and alumni. FETP is a CDC-supported epidemiology-training program that provides epidemiologists with the skills to become true disease detectives. The team had an important role identifying a total of three Ebola confirmed cases in Uganda and tracking down more than 100 contacts of these cases.

For more than 10 years CDC has supported and collaborated with the Uganda Virus Research Institute’s (UVRI) viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) laboratory. This established regional reference center for Ebola virus testing has tested, in real time, specimens from suspected Ebola cases and other VHF infections. Since the Ebola outbreak started in DRC, UVRI confirmed the three imported cases in Uganda. As of July 11, 2019 UVRI has tested almost 800 specimens suspected for Ebola, including close to 500 specimens from high-risk districts. In addition, healthcare and frontline workers have been vaccinated in 14 out of 30 high-risk districts, and this effort is ongoing.

Port health staff looking at a "sick" person standing in line at the airport during the simulation exercise. Photo credit: Irene Nabusoba

Leocadia Kwagonza is a FETP graduate who now works for Uganda’s MOH leading the data management team for the current Ebola response. She has handled more than 10 previous outbreaks, but noted how Uganda’s preparedness and community efforts have made a difference.

“Many of the other outbreaks including some viral hemorrhagic fevers are difficult to identify at first, making it challenging to determine how to best respond. However, for this Ebola response, we had been prepared for a long time and the response structures are very well known even in the [Kasese] district. This was different because we were in anticipation mode,” said Kwagonza. “The community-led response in this current Ebola outbreak also made it easier especially in owning and taking up the interventions. There is always a community component, but this one has been awesome. There is a lot to learn from this experience not only for Uganda but for other countries as well.”

CDC, the Uganda government and other partners have collaborated to build global health security capacity for full-fledged, real time deployment and response. These efforts show how Uganda can put preparedness into action.

The simulation exercise tested Uganda's capacity to safely transport samples of a dangerous pathogen. Photo credit: Irene Nabusoba