CDC supports the first Medically Assisted Therapy program that reduces HIV infections among drug users in Uganda

A CDC-supported program in Uganda, that opened its doors in October 2020, is already helping treat persons who inject drugs (PWIDs), a vulnerable population for HIV infection. Some patients are serving as volunteer peer educators.

The Medically-Assisted Therapy (MAT) program, the first of its kind in the country, was possible through a PEPFAR investment of $300,000 and CDC technical assistance in collaboration with the Uganda Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), the Ministry of Health, and Uganda Harm Reduction Network (UHRN).

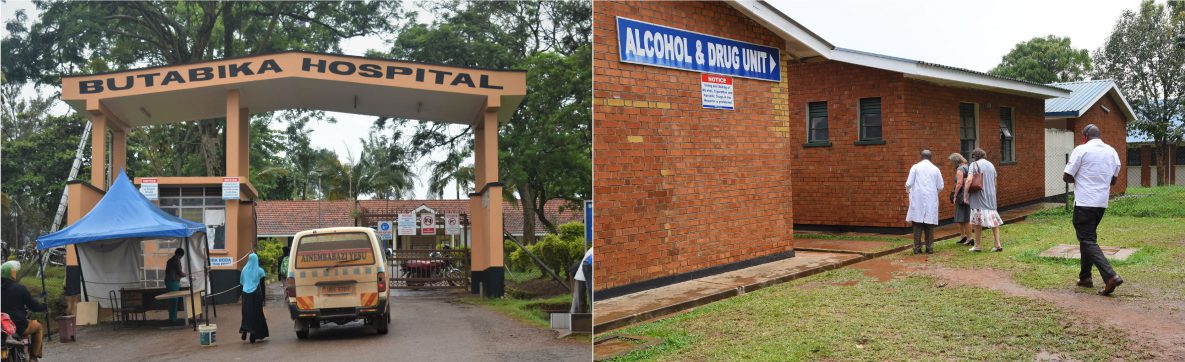

In Uganda there is a scarcity of harm reduction services or organizations to help to abstain from or reduce drug use. There are private rehabilitation centers, but they are costly and inaccessible for the majority of drug users. The free MAT program, housed at Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital’s Alcohol and Drug Unit, expects to reach 300 clients by end of 2021.

A client (in red hooded jacket) shares his addiction story and how MAT is helping him.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

Drug abuse is associated with major health and social economic consequences including higher risk of mental health issues, HIV, TB, and hepatitis B and C infections. Makerere University Crane Surveys, funded by PEPFAR through CDC, found an HIV prevalence among PWID of 17% (higher for women at 24%)—against the national prevalence of 6.2%; while hepatitis B prevalence was 20%. TB remains the leading cause of death among people who use drugs and are also living with HIV. The absence of tailored TB care for PWIDs leads to low levels of diagnosis, treatment, and multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB).

The UNAIDS Fast Track strategy on ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 demands that HIV-high burden countries focus on key population groups such as sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender people, persons in prisons and closed settings, and PWIDs because they experience high rates of HIV globally, difficulty accessing services, disproportionate social stigma and discrimination and are often criminalised by the law.

CDC Uganda Country Director Dr. Lisa Nelson (R) participates in the ribbon cutting ceremony to officially launch the MAT clinic on Dec 4, 2020.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

CDC Uganda Country Director Lisa Nelson and Deputy Jessica Conley interact with some of the clients and treatment buddies/parents at the MAT clinic. Looking on are staff from CDC, IDI, UHRN, and Butabika Hospital MAT staff.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

Speaking during the launch of the MAT on December 4, 2020, CDC Uganda Country Director Dr. Lisa Nelson noted that the program would extend PEPFAR services to vulnerable and marginalised groups that “most need our services and will help improve the quality of life for PWIDs.”

How the MAT program works

Butabika Mental Hospital is the first point of care for many families to help rehabilitate their loved ones struggling with mental health issues as well as alcohol and drug addiction. CDC refurbished part of the Alcohol and Drug Unit to house the MAT clinic—including clinical rooms and securing storage for the replacement methadone drug that can help prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Hospital entrance signage with directions to the Alcohol and Drug unit where MAT is housed.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

CDC Uganda Country Director Lisa Nelson (L), Deputy Jessica Conley (C), on a guided tour to the Butabika Hospital Alcohol and Drug Unit.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

CDC also supported hiring and training of staff to build the skills and knowledge to run the program. The training included study tours to other successful MAT clinics in Tanzania and Kenya. The program has already enrolled 78 individuals since its opening on October 1, 2020, with appointment adherence of 97%.

“It is a pilot,” explained Dr. Stella Alamo, CDC Uganda’s Prevention Branch Chief. Dr. Alamo has been at the forefront of starting this MAT program. “We hope to roll out services across the country with Ministry (of Health) ownership. As it is now, we can only serve one in 20 clients in need coming from across the country.”

MAT Program Offers Comprehensive Health Services

Besides Methadone maintenance therapy, the MAT program offers comprehensive health services, including:

- HIV counseling and prevention services (such as condom demonstration and distribution), testing, and HIV treatment (antiretroviral therapy). Eleven of the 78 clients so far enrolled have HIV—three were recently diagnosed while eight were already on treatment.

- TB testing and treatment

- Hepatitis B & C testing and related services

- Reproductive health including testing and treatment of other sexually transmitted illnesses; and referral for antenatal care and family planning

- Mental health assessment and treatment

- General medical treatment such as wound and abscess care

- Psychosocial intervention including counselling, family reintegration, occupational therapy

Enrollment and eligibility criteria

While pockets of negative public perceptions to people who inject drugs or PWIDs still exist, Ugandans increasingly acknowledge the growing problem of drug addiction in the country (especially among the youth)—and that this group needs help and friendly health services.

Uganda Harm Reduction Network (UHRN), a non-government organization that links clients to the MAT program, champions awareness about drug addiction and advocacy for tailored health services and rehabilitation interventions for people struggling with drug addiction.

“I was personally arrested for ‘mistakenly’ promoting drug abuse because of working with addicts. The police asked me to take them to the dens, identify the cartels…but I declined. I used the opportunity to educate them how supporting drug users to reform can help reduce crime. Today, police are one of our main partners in identifying and rehabilitating people who use drugs,” said UHRN Executive Director Twaibu Wamala.

Left to Right: Dr. Brian Mutamba—Head of the Alcohol and Drug Unit (front, right in clinical coat) takes CDC Uganda Country Director Lisa Nelson (L) and her deputy on a guided tour of the facility; the MAT clinic receptionist explains to the team how the clients are triaged in care; Dr. Nelson and team interact with some of the clients.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

The program is experiencing overwhelming interest from interested clients and UHRN established a careful enrollment process that includes a thorough screening process.

“We want those who are badly off and want to stop the addiction because MAT is just part of a broader treatment plan that needs strict adherence,” Wamala explained. “We look at how long one has been on drugs, work with the health workers to do clinical tests on toxicity levels and other health issues… But most importantly, one has to understand and commit that once enrolled, he or she will take the (methadone) drug every day at a given time for at least one year—though others stay on it for two years, depending on the level of toxicity and other underlying conditions.”

Methadone is in liquid form and each dose is accurately titrated by the clinic’s pharmacist and administered under direct observation. The client is expected to present a treatment buddy (a friend, family member) for support. “Then we start the process with counselling and support the clients through to restored health,” Wamala explained.

CDC Uganda Country Director Lisa Nelson, Prevention Branch Chief Dr Stella Alamo and Key Populations Specialist Simon Sigirenda pose for a photo at the clinic after the launch.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

Clients become peer educators

Some of the first clients now volunteer as peer educators. They can reach out to friends and provide resourceful information. Jacques and Sylvie (pseudonyms) are among these clients and shared their stories.

“I did not know anything about heroin, although I had been casually smoking marijuana since high school,” said Jacques, 32 years old. “While in my second year at university, I leisurely stopped by a bar on my way home to pick my pastime roll of marijuana, but I noticed it was way smaller than usual. When I protested, the guy simply responded, ‘try it, you will tell me. I have done a modern cocktail for you.’ And that was it.”

Within months Jacques was paying $20 for a shot of heroine. He was hooked. He would smoke it, inject it, and mix it with other drugs including cocaine. The Information Technology student dropped out of university and ran away from home to the drug dens, where he engaged in criminal activities to sustain his addiction.

Jacques had a turning point. “I was rescued by police from a mob that killed my friends, but they could not hold me for long because of Turkiyes’ (withdrawal symptoms). They thought I would die. They released me. My celebration was short-lived as my girlfriend soon died of an overdose. In my over 10 years of addiction, I had watched about 10 of my colleagues die from overdose but this was close to my heart. I knew I had to stop, or I would die,” he recounts.

When Jacques learned of the MAT program, he immediately enrolled and is sober now. “I want to meet my parents, whom I have not seen for 11 years, once I am five months off drugs.”

While for Sylvie, 28 years old, it was love at first sight—both for the boyfriend and drugs.

Jacques, speaking to the author, now volunteers as a peer educator.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

“It was our first semester at campus (university), and I was excited to be hanging out at night,” she recalled. “My boyfriend was 23 and had been at it (addicted to drugs) for a while and knew where to get every drug—from ‘shisha’, to heroin, cocaine, even prescription-only opioids. He had the money.”

The law student at the country’s top university dropped out in her second year.

“Sometimes my boyfriend would not be around, and I would have to secure the drugs myself. My pocket money was not enough, and I eventually encroached on the tuition. Soon, I was taking money from my mom’s bag, selling things at home—phones, flower vases, jewelry… I even sold the home TV to buy my ‘fix’. When I would get home, people would lock their doors because anything I would see tangible or valuable, I would steal and sell.

The couple’s families teamed up and sent the boyfriend to a rehab center in another country (he is now off drugs) and Sylvie to local rehabilitation centers.

“I have files in every rehab in the country,” she said. “I have been here (at Butabika Mental Hospital) like six times. I lost eight friends in my 9-year journey with addiction—to dangerous abortions, AIDS, violence, while two died of overdose—right in front of me. You would think that should have been my turning point but instead we would book more tickets (drugs) to celebrate a fallen colleague.”

Sylvie’s turning point: “My pregnancy,” she said rubbing her visible bump. “I’m due in two months, I’m very excited.”

Sylvie was contemplating a dangerous abortion when she learned of MAT. She approached the team that was conducting the sensitization session and enrolled. “And then COVID happened. I do not know whether I would be still alive,” she said. “I’m doing this (ceasing drugs) for my longtime boyfriend who has remained with me despite all—and especially for my family that have struggled with me for so long. I have been off drugs for two months now and the colors are brighter.”

Burden and consequences of drug use in Uganda

Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital offers specialized and general mental health services. The facility’s Alcohol and Drug Unit receives an average of 200 clients annually, most of whom are youths battling substance addiction.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

A 2018 population size estimate study by Makerere University Crane Survey found 3,837 PWIDs in the capital of Kampala alone. UHRN data estimates that 11,000-20,000 people inject drugs across the country.

There is growing evidence that non-injecting drug users eventually transition to PWID. A recent study found that over 81% of non-injecting drug users transitioned into PWID by the age of 24 years with nearly 85% sharing needles at their first injection.

As it is world over, Uganda’s drug addiction problem affects both males and females—though more prevalent among boys and men. Above: some of the clients (PWIDs) during the MAT launch.

Credit: Irene Nabusoba/CDC

For Jacques and Sylvie, the future looks brighter and now both participate in MAT outreach efforts.

“I just want to make a difference in the world by raising awareness about this disease that is spreading so fast,” said Jacques.

As for Sylvie, “I can sleep peacefully. I like to put on make-up and look beautiful. I’m trying to reconnect with my family and old friends—who are anxiously waiting for this little princess.”