Quietly, Burkina Faso Makes Changes That Protect Health At Home and Abroad

It’s easy to understand why most Americans don’t immediately (or ever) think “Burkina Faso” when asked about places where work is being done to protect them from infectious diseases and fast-moving outbreaks.

After all, not many people outside of Africa even know where the country is without checking Google or some other search engine. But that doesn’t minimize the changes and advancements that have taken root in this impoverished, land-locked nation, and why experts from across CDC are actively – and closely – involved. It’s also why they believe Burkina Faso could be a model of the broader global efforts to strengthen defenses against outbreaks.

Prof. Zeikba Tarangada, Director of Institute for Research into Science and Health, which includes Burkina Faso’s national influenza reference lab, has spearheaded efforts to strengthen lab performance and reliability. Tarangada, seen here with Dr. Adama N’Dir from CDC’s Burkina Faso office, is using new, sophisticated equipment to test now for 33 pathogens. Just one year ago, the lab’s capacity for finding pathogens in respiratory illness specimens was limited to influenza only. . (Source: Charles Pope, CDC)

Over the past year alone, Burkina Faso has taken a series of steps that collectively give health officials stronger, more accurate tools for detecting disease outbreaks and trends far quicker than before. There also is an enhanced ability to correctly detect a health problem’s cause, and a more unified and efficient communications system that ensures all the people and agencies involved have the information they need.

The upgrades and commitment from Burkina’s health leadership and senior government officials are significant and go beyond improving health for the country’s 18 million people. With relatively good roads and stable government, Burkina Faso is a crossroad for commerce and travel. It’s bordered to the north and east by Mali and Niger, both of which confront persistent insurgencies and hunger that keep people away, and on the south by Ghana and the Ivory Coast. Burkina Faso’s geographic position amid surrounding conflict and desperation illustrates why its ability to identify and respond to disease threats and outbreaks is important.

Burkina Faso is relevant for another reason as well. With its full-fledged commitment and ambition to become a leader for protecting people’s health, the country has positioned itself as a test site and barometer of efforts to strength global health protection embodied by a 2014 initiative known as the Global Health Security Agenda. The initiative now includes more than 60 countries in a joint effort to close gaps that allow diseases to take root and spread.

The improvements in Burkina Faso are often subtle and hard to see. But they are real and sturdy, whether they are unfolding in the bustling capital of Ouagadougou, where an Emergency Operations Center is scheduled to open soon, or beyond. These improvements can also be seen in the country’s second-largest city, Bobo-Dioulasso, where many of the nation’s reference laboratories are embedded within public research institutes such as the Centre Muraz and the Institute for Research into Science and Health.

With CDC support, these labs are enhancing their diagnostic capacity. For example, the national influenza reference lab acquired new, more sophisticated equipment and laboratory reagents and can now test for 33 different pathogens causing respiratory illness, including those triggered by bacteria and viruses; previously scientists in this lab were only able to test for influenza.

The on-the-ground results are real and measurable. In 2015, for example, the influenza reference lab’s heightened capabilities identified an outbreak of bird flu in a community 30 kilometers from Ouagadougou, a city of 2.2 million people. Working with the Ministry of Animal Resources, the source of the outbreak was confirmed, 120,000 birds were destroyed, and the threat was removed.

The lab has earned such a strong reputation that it is one of the labs worldwide contributing data to the WHO’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System that collects data used to develop each year’s flu vaccine.

A strong lab, said director Prof. Zekiba Tarnagda, “helps the Ministry of Health make decisions at the national level because it has better information and knows what was circulating and what is not.” With advanced degrees from institutions in Ukraine and from sessions at CDC, Tarnagda knows the importance of strong labs.

The advances can be seen too at a dusty health clinic in the tiny village of Dougoumato on a blistering hot day in April, when more than 400 people from the village and surrounding area gathered for hours under the one large tree for a tutorial on community event-based surveillance, a method used to identify and report unusual health events in the community.

Presenters used flip-books to illustrate basic concepts about disease recognition to more than 400 residents from the small village of Dougoumato as part of Burkina Faso’s effort to broaden its ability to detect potential disease threats. (Source: Evelyn Hockstein, CDC Foundation)

The idea is to help people in identify unusual ailments and health conditions such as severe respiratory illness. The goal is to increase the chances that any “hotspots” can be quickly recognized, reported, and addressed. The effort is based on the idea that more “eyes” you have looking for disease the better the chances that a potential health threat will be “seen” and reported.

Sampoue Kamlodo, a village chief, said people are willing to support the effort in large part because the presence of the local health clinic has been a popular and heavily-used benefit. People, he said, have developed a tight bond and trust with the nurses who work there.

“Before we had to travel a long distance to get treatment,” Kamlodo said. “But now the clinic is here and it has become too popular; the nurses are overwhelmed. We need more nurses.”

Crowded as it might be, the people have a history of responding to requests. Kamlodo pointed to an earlier effort to vaccinate people in the village for polio. Initially, mothers objected, uncertain about the motives, purpose, and importance of the immunization campaign.

“But soon they discussed it with the local nurses who they knew and trusted, and the nurses convinced the mothers the vaccine was good and they all agreed,” he said.

A similar expectation follows the surveillance effort. So far, the effort is being piloted in three health districts – Boussé, Kongoussi, and Houndé, which includes Dougoumato. As envisioned, the effort will serve as an early warning system and substantially improve detection and reporting of potential disease threats. It will build on an existing nationwide system of community health workers, community clinics, and health centers.

Villagers from Dougoumato listen to a presentation about disease identification. The session is designed to broaden the ability of Burkina Faso to detect disease and is just one element of a larger initiative supported by CDC to strengthen disease detection, response, and prevention in a key disease corridor in West Africa. (Source: Evelyn Hockstein, CDC/Foundation)

The advances in Burkina Faso dovetail with priorities that CDC officials in the country and in Atlanta have identified as well. Among the highest profile activities are programs to combat meningitis, such as MenAfriNet, a coalition of international partners locking arms to provide data on the impact of a new meningitis vaccine first introduced in 2010. It also includes robust interest in training programs such as CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP), laboratory upgrades that improves detection and surveillance, event-based surveillance, and efforts to combat the growing menace of antimicrobial resistance.

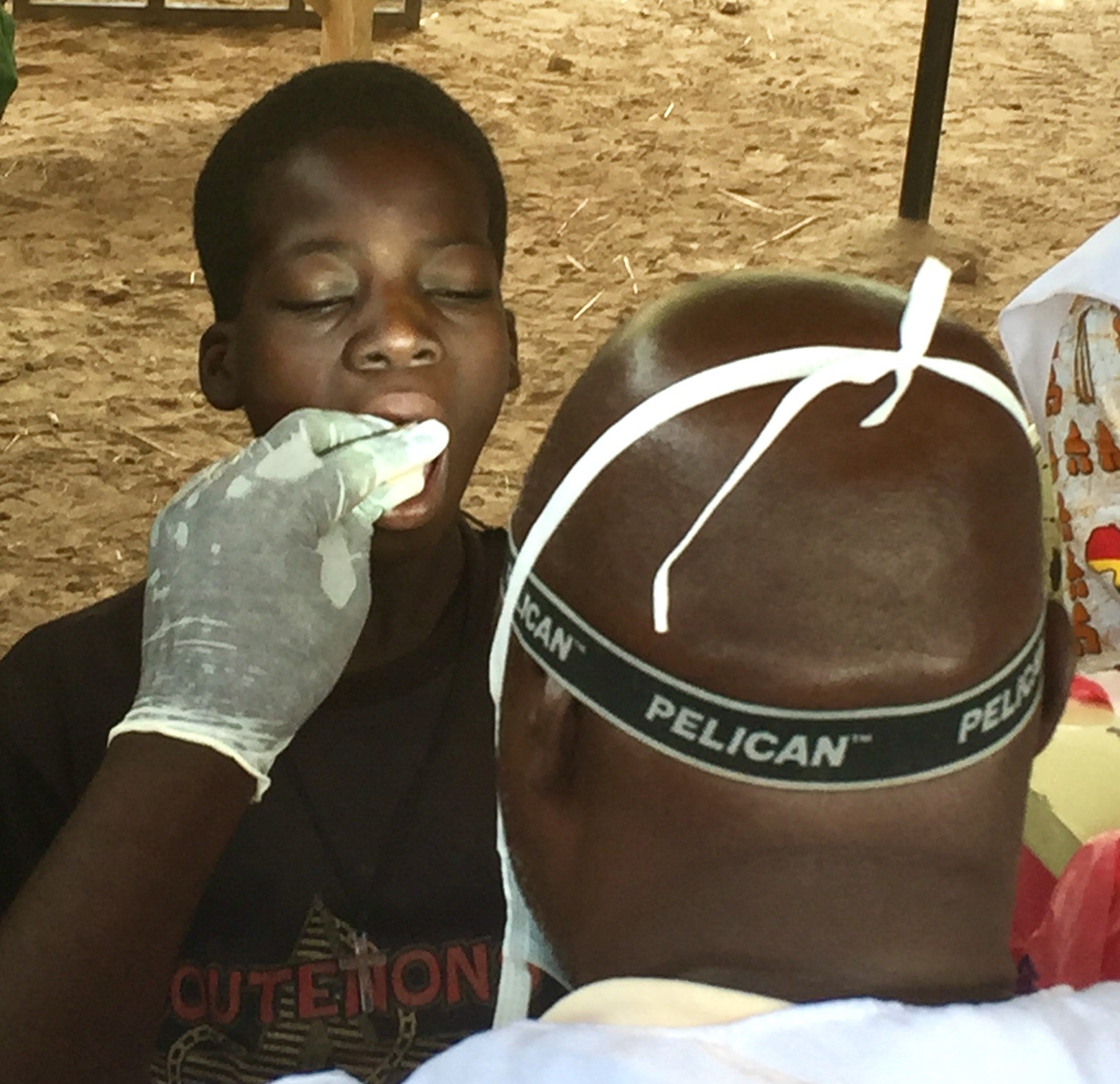

A technician swabs the cheek of a child as part of an effort supported by CDC to gauge the long-term impact of a new meningitis vaccine at a makeshift clinic in a remote village two hours from Burkina Faso’s capital. (Source: Charles Pope, CDC)

While there are occasional differences over priorities, the collaboration of CDC and its partners, including WHO and USAID, with the Ministry of Health are remarkably positive and cooperative.

“As the US public health institute with a breadth and depth of experts in disease prevention and control, CDC has a unique and important role to play in accompanying our Ministry of Health partners to strengthen their public health systems to better protect their own populations and the world from the threats of infectious diseases,” said Rebecca Greco Kone, director of CDC’s operation in Burkina Faso.

“For CDC to be successful in achieving our goals and objectives, we must first ensure our activities are supporting the priorities determined by the Ministry of Health and then by partnering hand in hand, in a concrete way, especially with key partners such as the World Health Organization and the US Agency for International Development (USAID),” she said.

Rebecca Greco Kone (R), director of CDC’s office in Burkina Faso, seen here with Minister of Health Professor Nicolas Meda (center), has developed a strong and productive relationship with the country’s public health leaders and partner organizations. (Source: Evelyn Hockstein, CDC Foundation)

The relationship has led to a number of important advances, including the identification of a building and a timeline for opening an Emergency Operations Center, a key facility that acts a hub for information and is an essential mechanism for coordinating effective responses when outbreaks occur.

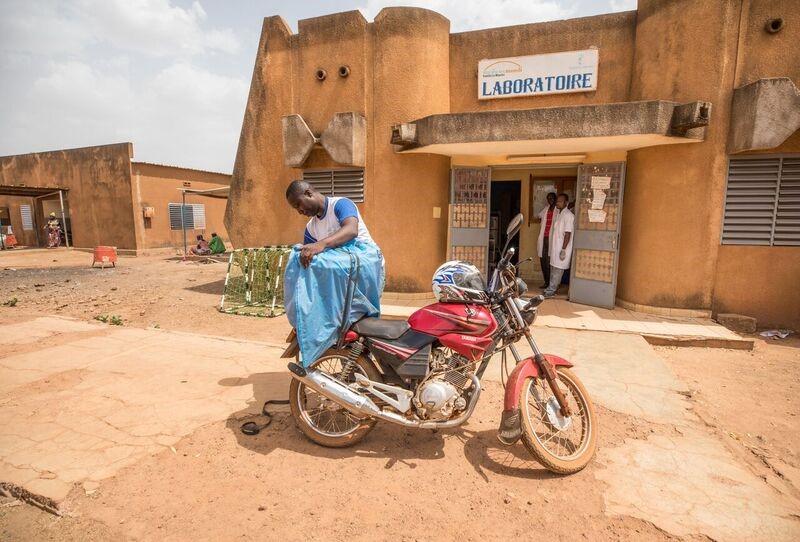

The collaboration has helped bring about a new method for collecting and delivering samples from health centers to laboratories, and for the data to be collected and maintained in a uniform way and reliably delivered. The new system relies on motorcycle couriers from Burkina Faso’s national postal service that ensure samples are delivered to labs within 48 hours so they can be tested and the data transmitted to health centers, regional facilities, and the Ministry of Health. All the work and collaborations provide strong new tools for spotting trends and medical developments faster and with more certainty.

A new system for collecting and delivering lab samples using Burkina Faso’s national postal service adds crucial reliability and data that public health leaders can use to better pinpoint trends, outbreaks, and actions. (Source: Evelyn Hockstein, CDC Foundation)

Individually, each advance and upgrade is easy to miss. But taken together, the changes and improvements, the sustained dedication and commitment to putting in place all the mechanisms and people and policies, has made Burkina Faso a healthier place.

In an era where any disease can travel from a remote village to cities on all six continents in as little as 36 hours, the actions taken in Burkina Faso and the example it sets means that people in the United States and across the globe are safer as well.