CDC and Thailand Partnership Improves Lab Testing for Zika Virus

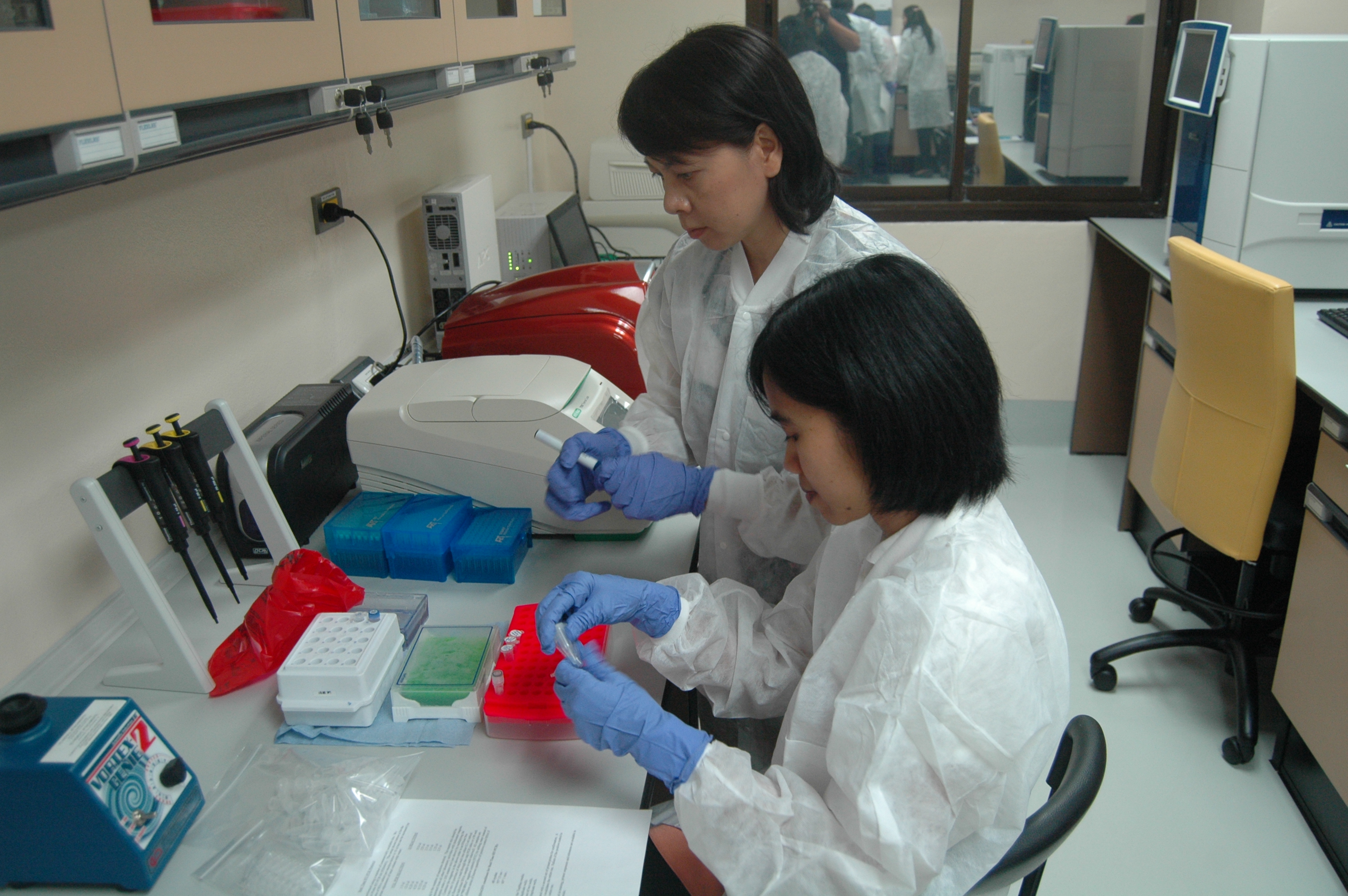

Laboratory workers from the National Institute of Health and Chulalongkorn University display certificates after successfully completing a training on how to identify Zika and Chikungunya viruses.

THE PROBLEM: After detecting cases of Zika in returned travelers, Thailand needed to increase its laboratory testing capacity for Zika and other viruses.

SOLUTION: Following the request of Thailand’s MOPH, CDC trained the country’s laboratory workforce, helping to increase testing capacity for Zika and other viruses. A routine Zika surveillance system was also established.

Thailand, a tourism hub in Asia, demonstrates how the interconnectedness of the world today makes it easy for viruses to travel across borders. In 2013, tourists returning home not only brought back souvenirs from their vacation, they also tested positive for Zika virus (Zika) infection, which spurred Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) to ask CDC for help to improve its laboratory testing capabilities for Zika and other viruses such as SARS, avian influenza. Now the country is one of the first in Asia with the ability to test for Zika.

Zika virus, carried by Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes and spread primarily through a bite, is found throughout Asia, Africa, North and South America, Oceania, and the Pacific Islands. Many people who get infected with Zika will have mild fever, rash, joint pain, conjunctivitis (red eyes), muscle pain, and headache or no symptoms at all, making diagnosis difficult. Although most people recover without problems, severe outcomes can occur. Among these outcomes is Guillain-Barré syndrome, an uncommon sickness of the nervous system that can lead to paralysis. One of the biggest threat from Zika is to the fetus of an infected mother. Zika can cause severe fetal brain defects, as well as eye, hearing, and growth problems.

In 2014, after receiving reports of tourists to Thailand returning home and being diagnosed with Zika, CDC answered a request from MOPH to help improve its laboratory testing for the virus. CDC experts from Ft. Collins traveled to Thailand and trained laboratory workers at the National Institute of Health, Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute, and the Virology Department at Chulalongkorn University on how to identify Zika and Chikungunya viruses in blood, serum and urine. Soon after, CDC and MOPH began testing patient specimens collected during outbreak investigations conducted from 2012 through 2014 to determine what caused the illnesses. Lab tests confirmed Zika outbreaks occurred during this period.

Laboratory workers from Thailand’s National Institute of Health and Chulalongkorn University learn to identify Zika and Chikungunya viruses.

With the onset of Zika outbreaks in South America, MOPH has enhanced Zika surveillance throughout the country. The strong partnership between CDC and MOPH has improved Thailand’s ability to detect Zika. In 2016, Thailand tested approximately 18,000 specimens and identified more than 520 Zika-positive specimens, including 50 from pregnant women. Surveillance also detected two cases of Zika related microcephaly in children.

CDC continues to partner with Thailand’s MOPH to expand surveillance for Zika, including surveillance for patients hospitalized with fever in two border provinces. Plans are underway to determine how to measure the effect of Zika infection on pregnant women, monitor babies’ health at the time of birth, and understand the risk factors associated with infection in pregnant women.

About this Story

CDC is working with 31 priority countries to develop global health security capabilities, which protect Americans and people around the world from disease threats. This story illustrates Thailand’s commitment to

- Real-Time Surveillance: Launching and strengthening global networks of disease-surveillance systems that quickly detect outbreaks and assess risks.

- National Laboratory System: Establishing a nationwide laboratory system that uses modern diagnostic technology to safely and accurately detect and identify pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses, which cause infectious diseases.

CDC will continue to work with the government of Thailand to improve its national laboratory system, Zika surveillance and reporting, and to increase the number of trained public health workers. This work ensures that Thailand, and subsequently the global community, is safer from disease threats.