Confronting Malaria on the Frontline in Nigeria

This web page is archived for historical purposes and is no longer being updated.

Photo credit: Patrick Kachur/CDC

Fatima is a compact and energetic woman who serves as primary health care coordinator for the local government in a part of northern Nigeria known as Gwale.

Her energy and determination are necessary, because the work she performs in public health in Gwale may be among the toughest imaginable.

With just 24 health facilities available to serve the comprehensive needs of more than 500,000, the people and facilities are strained from high demand. Perched on the edge of the Kano municipality, one of the largest indigenous cities in Africa, Gwale is a place of stark contrasts. And those contrasts have a direct effect on the work being done by Fatima and others to protect people from disease and improve their health.

One focus is polio. With support from CDC and the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) program, Fatima and her team had rallied effectively to eliminate polio transmission despite earlier setbacks. Now they’re using some of the same strategies to confront malaria—the leading cause of illness in the communities they serve.

The work Fatima and others do is a good example of how “best practices” from one effort are being adapted and successfully applied to fight threats to people from other diseases and across differing cultures and economic conditions.

For thousands of years this part of Nigeria has been a center of commerce and migration. These days, smartly dressed young people participate fully in the globalized commercial economy from the gleaming banks and office blocks in Kano’s Central Business District. But the opportunities for true affluence are rare and relatively new. The vast majority of people in Gwale engage in far more modest lifestyles, with many working as traders struggling to raise millet, sorghum, or livestock on parched and depleted land. It is a place where local officials might be easily overwhelmed by the size of their task and the relative lack of information and resources available to make a difference. But that is not Fatima’s story.

In 2015, CDC, the Nigeria National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP), the Nigeria Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Program (NFELTP), and the NSTOP program initiated the NSTOP/Malaria Frontline project to improve the effectiveness of malaria control in Nigeria by strengthening the technical capacity of Nigeria’s public health system to reduce malaria, as well as improving the tools and policies used to prevent, detect, and respond to epidemics and other endemic high-impact diseases.

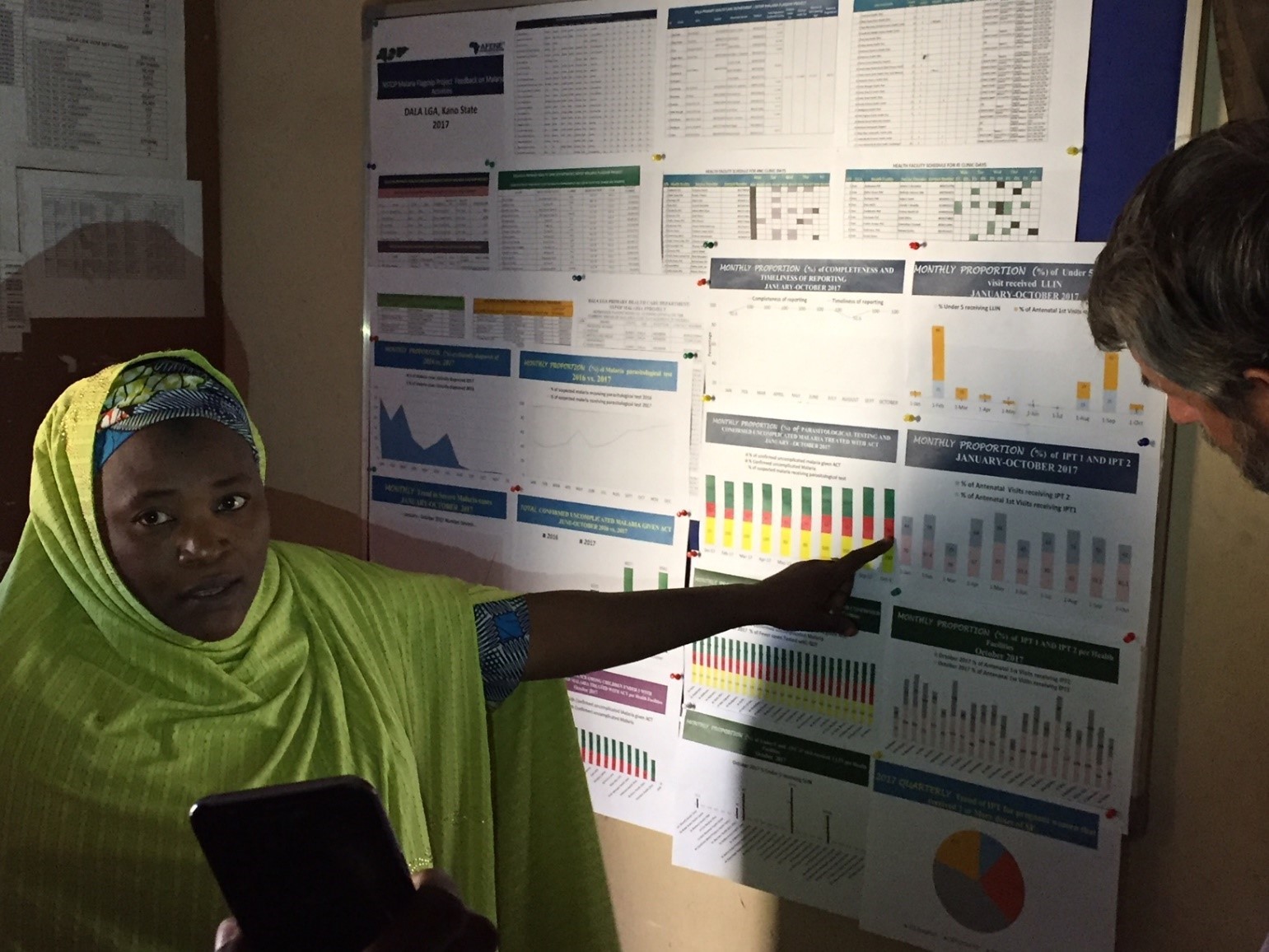

PHC Coordinator Aisha Adam explains malaria data at Dala LGA. Photo credit: Patrick Kachur/CDC

This project builds on the experience gained from polio eradication efforts and the Ebola response, to strengthen capacity at the facility, local government area (LGA), and state levels to analyze and use malaria surveillance data for decision-making in Kano and Zamfara states. The project adapts the NSTOP model to improve surveillance, identify intervention coverage gaps, conduct supportive supervision, and provide in-service training to facility staff. The NSTOP/Malaria Frontline project is collaborating with the Government of Nigeria (GoN) and other stakeholders including The U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), the Department for International Development (DfID) in the United Kingdom, WHO, and UNICEF on implementing malaria activities.

Over the past year, the Malaria Frontline Project provided training, on-site mentorship, and technical support to local government health officials across Kano and Zamfara State. Now Fatima and others like her can carefully monitor the stocks of malaria prevention and treatment supplies and trends in local illness cases diagnosed and treated in each of the health facilities. They are able to use data to spot early trends and target emergency supplies and outreach efforts at the time and place where they’ll do the most good.

“If there is no data, there is no progress. Each month we look and see where problems are and how we can improve,” said the clinician in charge of one health post.

This effort to collect and utilize malaria data locally is part of a needed reset for malaria programs in densely populated, high-burden places like rural Nigeria.

Last year, the World Malaria Report noted an increase in the global numbers of malaria illnesses and deaths for the first time in more than a decade. And much of that could be traced to the fact that life-saving interventions like bednets, house spraying, and diagnosis and treatment of malaria cases—tools that have saved more than seven million lives—still failed to reach some of the places where they’re needed most urgently. For the past 12 or 15 years, malaria control programs and their global partners have achieved dramatic progress by deploying these tools everywhere they can afford to do so. But the resources, especially in a place like Kano State, consistently fall short. At the same time, maturing health information systems based on the routine use of malaria diagnostic testing have begun to generate reliable local and national data that will allow malaria officials to target their efforts and achieve better results.

As World Malaria Day approaches April 25, global advocates are calling for better information and targeting of malaria efforts in high-burden areas and more careful subnational and local decision-making. It will involve transforming malaria surveillance and health information into a key tool, as integral and important as net campaigns and treatment drugs. The Nigeria Frontline Project offers a valuable early example of how this approach might be affordable and achievable.

And Fatima is leading the way.