CDC EIS Officer helped ambulance staff avoid Ebola infection in Sierra Leone

Tiffany Walker, MD, is an Epidemiology Intelligence Service (EIS) Officer in CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases.

Everyone involved in the effort to get to zero Ebola cases knows a key to controlling the spread of disease is quickly isolating any person believed to have the virus. Healthcare workers, including ambulance teams, are particularly at risk. Public health officials, including surveillance officers, have also gotten Ebola, especially in the early days of the outbreak when infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols were not as widely understood or easy to follow. CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) Officer Tiffany Walker, MD, was one of the first members of CDC’s IPC team in Sierra Leone to work alongside partner agencies and help ambulance drivers protect themselves from getting Ebola.

Dr. Walker was working in Bombali, a district about a three-hour drive northeast of Freetown, where CDC’s Sierra Leone headquarters is located. Her role was to monitor and train healthcare workers on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and IPC protocols. When she arrived, few standard operating procedures existed to evaluate correct use of PPE to limit exposure in ambulance and burial teams. The ambulance team in Bombali had just lost several members to Ebola. An investigation showed that ambulance drivers were, at that time, picking up patients with suspected Ebola, loading them in the ambulance, and then spraying themselves with a chlorine solution while wearing full PPE. After being sprayed down, they were leaving their suits on and driving to the Ebola holding centers.

Healthcare workers wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) as protection against Ebola in front of Connaught Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

One team member shared the front cab with the driver, who was not wearing PPE. “PPE should always be removed before entering the ambulance cab to prevent contamination,” said Dr. Walker. The ambulance driver became sick with Ebola, but continued to come to work. He spread Ebola to other members of the ambulance team.

Dr. Walker was determined to help prevent this from happening in the ambulance community. She rode in a car behind the ambulance to mentor the ambulance team. Observing how they worked with patients, she gave feedback and input on how well they were using IPC practices. When she saw them doing something that put them at risk, she talked them through steps to protect themselves and their teammates better the next time.

During her deployment in fall 2014, Dr. Walker developed a friendly and respectful relationship with the team. She says she felt as though she was making a difference and that the team took her recommendations and guidance seriously.

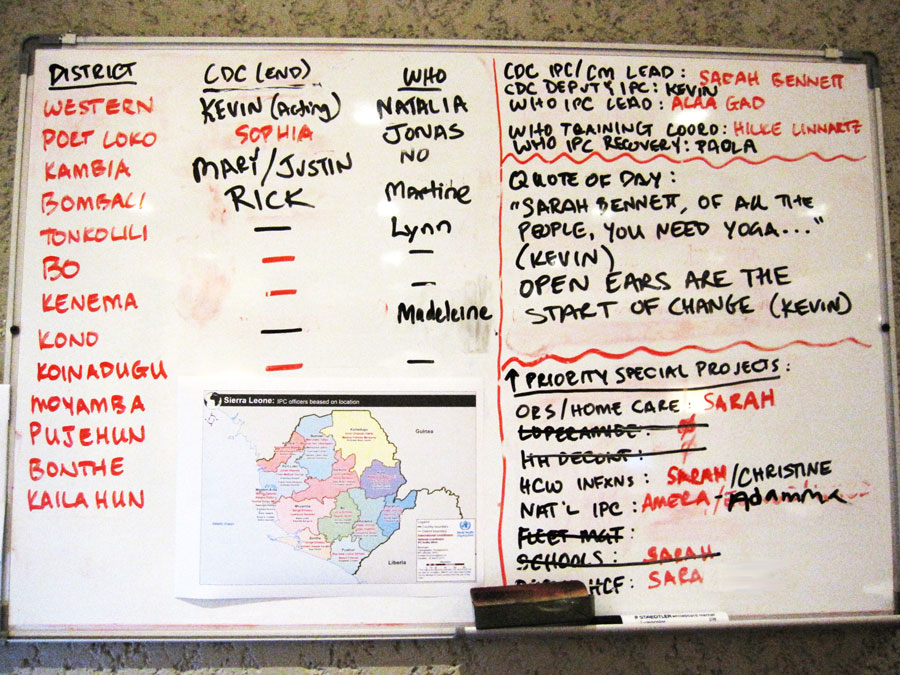

Infection prevention and control (IPC) team assignment board in the CDC-Sierra Leone headquarters in Freetown.

Dr. Walker also befriended a surveillance officer during a case investigation. One day, she learned from her supervisor that he had tested positive for Ebola. It turns out his blood was tested after he experienced mild symptoms consistent with Ebola. His test result was equivocal, requiring additional testing to determine a diagnosis. Dr. Walker rushed to where her friend was waiting for an ambulance to take him to an Ebola holding center for a repeat test. Other friends and colleagues were also there. “We were all scared for him and nervous as well for ourselves,” she said.

As the group waited for the ambulance, they gathered around their friend, keeping the required 1-meter recommended distance for IPC. Dr. Walker thought that if the initial test turned out to be a false positive, being in an ambulance and spending time in the Ebola holding center could expose him to Ebola. Before the ambulance arrived, Dr. Walker raced to her vehicle to get a set of PPE and offered it to her friend so he would be protected in the ambulance and in the holding center.

Eventually, the surveillance officer tested negative for Ebola. Reflecting on her reaction to her friend’s false positive test, Dr. Walker concluded, “I feel like this is an emotional fight rather than a rational one.”

In Sierra Leone, ambulance teams, surveillance officers, doctors, nurses, hygienists, and laboratory technicians continue to work even after losing friends and family. IPC supplies are now more readily available and protocols better known and used.

After leaving Sierra Leone from her first deployment, Walker kept in touch with several team members. When she returned for her second deployment in May as part of CDC’s Epidemiology Team, one of the ambulance drivers told her that he was able to return to technology school now that there are zero cases in Bombali District.

Dr. Walker described the selfless commitment of the drivers and other Ebola responders: “It was so humbling to see what they were going through. Responders from international organizations like CDC get to leave for a spell between deployments— Sierra Leone’s responders have been in it for a year without rest.”