Investigating Liver Disease in Ethiopia

Epidemiology is the science that investigates how, where, and when a disease occurs in a specific population. Epidemiologists are therefore “disease detectives” who apply science to solving real public health problems. At the CDC, the 160-member Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) is a corps of public health and medical professionals who serve two-year terms helping public health agencies in the U.S. and around the world with their investigations. EIS officers are medical doctors, PhD-level scientists, dentists, nurses, and veterinarians.

A strange new illness was spreading throughout Tigray, the northern region of Ethiopia. In this dry, mountainous area, people living in remote homes and villages were coming down with what appeared to be the same unknown disease. Residents of Tigray were all too familiar with the tropical diseases common in this region, and they recognized this illness was not one of them. But what was it?

People who contracted the disease developed swollen, painful abdomens and then lost weight. Some of them had trouble breathing as the fluid in their abdomens crowded against their lungs. Three or four family members in one household might become ill, while others living in the same household did not. However, in some families, everyone died from the disease. Even children as young as 5 years old became too weak to move, their abdomens swollen with up to four liters of fluid.

In this area of Ethiopia, people lead very basic lives. They grow their own food, mostly different types of grain, and keep animals. In 2002 when the disease was first reported, residents had limited access to medical care. The nearest health post may be several hours’ walk away and employ only one health extension worker with a high school education and some basic medical training. People were ill, even dying, from an illness that demonstrated symptoms commonly seen in liver disease. But what was causing it?

The Investigation Begins

A home in rural area of Tigray, Ethiopia.

In 2005 a multidisciplinary team began an investigation into the disease and its causes under the principle of the “One Health Approach.” The team included physicians, veterinarians, epidemiologists, anthropologists, and environmental and plant scientists. They came from the Ethiopia Ministry of Health and Ethiopia Health and Nutrition Research Institute (EHNRI), the Ethiopia Ministry of Agriculture, WHO-Ethiopia, Addis Ababa and Mekele Universities, Tigray Regional Health Bureaus and Tigray Agricultural and Rural Development Bureau. Despite their efforts, the mystery remained unsolved.

Matthew Murphy organizes the team for field work outside a health station. Photo by CDC staff

This was the situation in Tigray in 2007, when the Ethiopia Ministry of Health and EHNRI asked CDC and other partners to join the multidisciplinary team and help them investigate the outbreak of what was then called “unidentified liver disease (ULD).” Since 2005, more than 1,200 people had been diagnosed with the condition and many had died. The joint epidemiologic investigation in 2007 ruled out infectious diseases as the cause and suggested that the disease may be related to something in people’s diets. But EHNRI already suspected that the cause of the outbreak was something in the environment.

Field workers set off on their long walk to collect data. Photo by CDC staff

A year later, CDC staff including Matthew Murphy, PhD, MS; Colleen Martin, MSPH; Richard Luce, DVM, MPH; Danielle Rentz, PhD, MPH, and Eyasu Teshale, MD travelled to Tigray, Ethiopia to further assist EHNRI. The CDC team helped Ethiopian health agencies conduct another investigation to understand better the risk factors for the disease. The joint epidemiological teams walked to remote villages or homes, some as far as four hours away, to gather information from households with and without ULD.

Colleen Martin has vivid memories of her time in Ethiopia. “It was so sad to see small children with their swollen bellies, so sick they could not move,” she said. But these conditions just made her more determined. “I like tackling the problems in environmental epidemiology and working in countries with basic lifestyles where I can make a difference in the lives of people who need help.”

Although they still did not find a definite cause for ULD in 2008, the epidemiologists narrowed the list of possibilities. They discovered low levels of two particular types of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which are a large class of plant-based liver toxins, in grain samples taken from household farms where people had ULD. The toxin was found in a common type of weed that grew and was harvested along with the grain.

Based on this information, scientists believed that the cause of the outbreak might be exposure to toxic PAs from eating contaminated grain or animal products, but too many uncertainties remained.

- The levels of PAs in grain samples were too low to cause acute or chronic illness and had never been associated with toxicity before.

- Doctors had not been able to document completely the course of the disease in patients.

- Epidemiologic risk factors for illness were unclear.

- No laboratory test existed that could evaluate human serum (blood) for evidence of PA exposure.

Colleen Martin and Danielle Rentz organize supplies for field workers. Later, they would turn this dusty room into a “laboratory,” complete with centrifuge and freezer. Photo by CDC staff

The Plot Thickens

Danielle Buttke processes samples.

CDC epidemiologists knew they needed more information to come to solid conclusions; so they recommended collecting more grain and other food samples for testing, establishing a surveillance system, and collecting additional evidence from ULD patients to better describe characteristics of the disease.

Following these recommendations, in 2009, EHNRI established a surveillance system and in 2011, once again requested CDC assistance to develop tools to collect physical evidence from ULD patients and additional samples for PA testing. Epidemiologists Danielle Buttke, DVM, PhD, MPH; Ellen Yard, PhD; Richard Luce, DVM; and Tesfaye Bayleyegn, MD, travelled to Ethiopia to contribute their expertise, while Colleen Martin provided oversight from Atlanta.

Tesfaye Bayleyegn, a native Ethiopian, was of particular help during this investigation. He not only knew the language, but also the politics of the country and the culture and personal habits of the people who lived in Tigray. After medical school, Bayleyegn had worked as an anesthesiologist in Addis Ababa and for the World Health Organization. CDC then invited him as one of only a few international staff to participate in the EIS program, giving him further on-the-job training in epidemiology. “From the time I began medical school,” he said, “I thought only of dedicating myself to improving medical care in places in dire need.”

Tesfaye Bayleyegn and Hailemariam Hailemichael at regional hospital.

Bayleyegn did not know then that one of those places would be his native land. “When I worked for EIS in 2004-2006, I never dreamed that I would be involved in such an investigation and go back to my country with my CDC colleagues to share our experience and skill,” he said.

Laboratory tests indicated that patients with ULD and even some of their family members who did not have any ULD symptoms had signs of the kind of liver abnormalities that could be caused by PA exposure. But were these abnormalities specifically because of exposure to PAs? Investigators knew that the right blood tests could confirm that.

And for the first time, such a test was finally available. By 2011, the Chinese University of Hong Kong had developed a laboratory test to determine whether people had been exposed to PAs. This new test had been used only a few times in China, but seemed to be just what was needed for the investigation, so CDC epidemiologists negotiated with the the Chinese lab to process the blood samples from Tigray.

Environmental Evidence

Danielle Buttke takes a sample from a goat herd. Photo by CDC staff

In addition to the medical exams and tests, epidemiologists gathered information about how people took care of their crops and animals and what people ate and drank in homes with a ULD patient and in those without. Investigators also collected samples of grain, honey, and drinks, such as a local alcoholic beverage and milk, from households with and without the disease.

At this point, CDC got critical help from the Poisonous Plant Laboratory of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA lab analyzed the grain collected in the Tigray study and discovered important information.

- Grain PA levels were significantly higher in ULD households.

- Some grain types were more contaminated than others.

- The PA that was most commonly detected and at the highest levels was from a new plant source previously unidentified in this investigation, but known to cause toxicity and death in other parts of the world.

Investigation Outcome

Colleen Martin was alone in her office the day that the test results came in from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She was so eager to see what they revealed that she analyzed the data in just one day. Martin was elated! The results affirmed their hypothesis—50% of the ULD patients had test results indicating they had been exposed to PAs.

To date, this study is the largest that has measured PA exposure using blood serum. Test results showed that ULD patients, their family members, and even other members of the community who were not sick had been exposed to PAs. However, ULD patients had higher PA levels than village members who had no ULD symptoms.

The study also found that households with cases of ULD and those without ate the same foods and drank the same beverages. However, investigators discovered a very important difference between members of ULD and non-ULD households. People in households without ULD were more likely to separate the weeds from their crops both before and after harvest than people in households with the disease.

Eradicating ULD

Even though researchers can now more accurately pinpoint the cause of this deadly disease, there is still no cure. Therefore, to eradicate the disease in Tigray, eliminating the source of the toxin is essential.

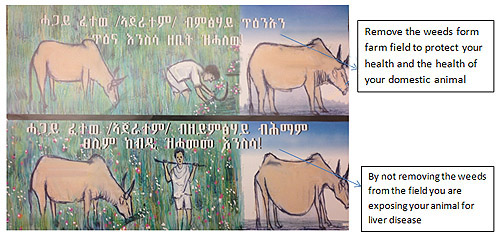

To do that, the health ministry, EHNRI, and health extension workers are focusing on educating the community about the importance of weeding crops. Separating weeds during the growing season and during the harvest are equally important. If weeds are in the fields along with the grain, the farmers will harvest them together. And when farmers separate the grain from the stems, the weeds can contaminate the entire harvest.

Health workers also tell farmers to monitor the health of livestock that can contract the disease by eating toxic weeds. Not only can the animals become sick or die, but also consuming milk or meat from contaminated animals can exposed people to toxic PAs.

Poster used to educate villagers about livestock. Photo by CDC staff

In addition to working directly with the affected communities, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health and EHNRI are spreading the word by radio. Even though their homes are spread far apart and they have no electricity, community members regularly rig up a battery-operated radio and put it high in a tree, then gather to listen to news reports. Families and villages across Tigray are getting the message, one way or another.

ULD Investigation Crosses Finish Line

Not all disease investigations have such a clear outcome, but the ULD study provides an example of epidemiology at its best. Bayleyegn and Martin compare the process to a relay, where a team member runs one leg of the race and passes the baton to the next runner. The last runner gets to carry it over the finish line because of the hard work of the entire team.

Similarly, epidemiologists and laboratory scientists from CDC and CDC Ethiopia, the USDA, EHNRI, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, Tigray Regional Health Bureau, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and others contributed their knowledge and expertise to studies with many different components over several years, each time building on the work of previous investigations.

Thanks to the skilled work of the “One Health” team and collaboration of local and overseas institutes, the term “ULD” is now outdated, because the cause of the liver disease is no longer unidentified. The disease is now called “pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced liver disease (PAILD)” for the toxic PA that causes the illness. More important, grain farmers in Ethiopia now have the information they need to protect themselves and their families from a once mysterious and sometimes fatal disease.