Mosquito Technology

Cutting mosquito populations in half in Ponce, Puerto Rico

Long before Liliana Sánchez-González became a doctor, she got very sick with dengue when she was a teenager in Colombia. She was lucky to live through it and, years later, found purpose in caring for her own patients with dengue. But she never dreamed she would one day coordinate a project aimed at ending dengue at the source, by releasing mosquitoes infected with the Wolbachia bacteria to breed with and stop the local mosquitoes that spread dengue.

Liliana was the lead coordinator for COPA (Communities Organized to Prevent Arboviruses), a collaboration with CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Ponce Health Science University, and the Puerto Rico Vector Control Unit. One of COPA’s goals was to assess the effectiveness of emerging mosquito control methods, like releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into the environment. When male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia are released and mate with wild female mosquitoes that do not have Wolbachia, the eggs will not hatch. This results in a reduction in the mosquito population.

Liliana Sánchez-González, MD, MPH COPA Lead Program Coordinator, CDC’s

NCEZID Division of Vector-Borne Diseases

“We worked with community promotores who had previously established relationships in the community. Gaining widespread buy-in and support meant that the community believed we had the best intentions of getting rid of dengue.’’

Assessing Effectiveness of Using Wolbachia-Infected Male Mosquitoes for Mosquito Control

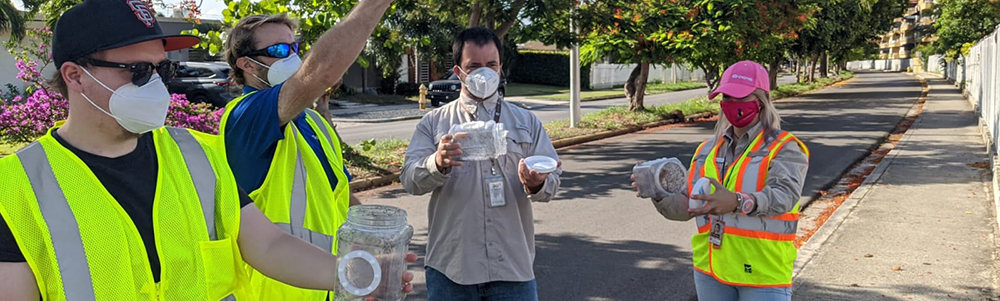

During the project, COPA staff released more than 90 million mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. “The logistics would make you think it was an impossible task,” said Liliana. “By working with promotores (community health workers) who had previously established relationships in the community, we made it happen.”

Working collaboratively with and through community partners, such as promotores is critical to cultivating community engagement and trust. It is also an effective way to mobilize resources, influence systems, improve public health programs, and ultimately improve the health of communities.

Preliminary analyses show local mosquito populations in some areas decreased by about 50%. “We had hoped to decrease mosquito populations more but are proud of this work and have learned that if we combine this method with other traditional mosquito control methods, we are likely to have even greater success,” said Liliana.

“Working on the Wolbachia release project positively impacted my career

path,” said Liliana. “I’ve never done this type of work before. On any given day, my work ranged from recruiting community participants to collecting data. Drawing on past experiences and learning new skills helped me grow as a researcher, clinician, and public health professional.”

This project is a step into the future for mosquito control in Puerto Rico. CDC and its partners have learned more about mosquitoes in Puerto Rico and how to implement emerging control methods. The door is now open for continued mosquito control projects and opportunities to evaluate impact on human health and build on existing partnerships and community engagement.

Controlling mosquitoes and preventing the viruses they spread continue to challenge public health professionals. After releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, local mosquito populations decreased by about 50% in some areas. Community health workers were key partners who helped make it happen.