2001 Surgeon General’s Report – Highlights

The Burden:

This year alone, lung cancer will kill nearly 68,000 U.S. women. That’s one in every four cancer deaths among women, and about 27,000 more deaths than from breast cancer (41,000). In 1999, approximately 165,000 women died prematurely from smoking-related diseases, like cancer and heart disease. Women also face unique health effects from smoking such as problems related to pregnancy.

The Trends:

In the 1990s, the decline in smoking rates among adult women stalled and, at the same time, rates were rising steeply among teenaged girls, blunting earlier progress. Smoking rates among women with less than a high school education are three times higher than for college graduates. Nearly all women who smoke started as teenagers—and 30% of high school senior girls are still current smokers.

The Hope:

We have the solutions for preventing and reducing smoking among women. Quitting smoking has great health benefits for women of all ages. Thanks to an aggressive, sustained anti-smoking program, California has seen a decline in women’s lung cancer rates while they are still rising in the rest of the country. The voice of women is needed to counter tobacco marketing campaigns that equate success for women with smoking.

“When calling attention to public health problems, we must not misuse the word ‘epidemic.’ But there is no better word to describe the 600-percent increase since 1950 in women’s death rates for lung cancer, a disease primarily caused by cigarette smoking. Clearly, smoking-related disease among women is a full-blown epidemic.”

David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., Surgeon General

Women and Smoking: a Report of the Surgeon General makes its overarching theme clear-smoking is a woman’s issue. This report summarizes what is now known about smoking among women, including patterns and trends in smoking habits, factors associated with starting to smoke and continuing to smoke, the consequences of smoking on women’s health and interventions for cessation and prevention. What the report also makes apparent is how the tobacco industry has historically and contemporarily created marketing specifically targeted at women. Smoking is the leading known cause of preventable death and disease among women. In 2000, far more women died of lung cancer than of breast cancer. A number of things need to be acted on to curb the epidemic of smoking and smoking-related diseases among women in the United States and throughout the world.

- Increase awareness of the impact of smoking on women’s health and counter the tobacco industry’s targeting of women.

- Support women’s anti-tobacco advocacy efforts and publicize that most women are nonsmokers.

- Continue to build the science base for understanding the health effects of smoking on women in particular.

- Act now: more than enough is already known to enable us to support efforts to stop smoking at both individual and societal levels.

- Do everything possible to stop the epidemic of smoking and smoking-related diseases among women globally.

Major Conclusions of the Surgeon General’s Report

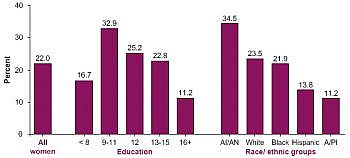

- Despite all that is known of the devastating health consequences of smoking, 22.0% of women smoked cigarettes in 1998. Cigarette smoking became prevalent among men before women, and smoking prevalence in the United States has always been lower among women than among men. However, the once-wide gender gap in smoking prevalence narrowed until the mid-1980s and has since remained fairly constant. Smoking prevalence today is nearly three times higher among women who have only 9 to 11 years of education (32.9%) than among women with 16 or more years of education (11.2%).

- In 2000, 29.7% of high school senior girls reported having smoked within the past 30 days. Smoking prevalence among white girls declined from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, followed by a decade of little change. Smoking prevalence then increased markedly in the early 1990s, and declined somewhat in the late 1990s. The increase dampened much of the earlier progress. Among black girls, smoking prevalence declined substantially from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, followed by some increases until the mid-1990s. Data on long-term trends in smoking prevalence among high school seniors of other racial or ethnic groups are not available.

- Since 1980, approximately 3 million U.S. women have died prematurely from smoking related neoplastic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and pediatric diseases, as well as cigarette-caused burns. Each year during the 1990s, U.S. women lost an estimated 2.1 million years of life due to these smoking attributable premature deaths. Additionally, women who smoke experience gender-specific health consequences, including increased risk of various adverse reproductive outcomes.

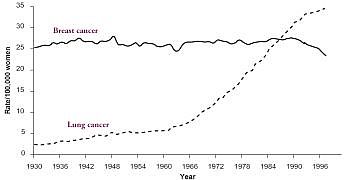

- Lung cancer is now the leading cause of cancer death among U.S. women; it surpassed breast cancer in 1987. About 90% of all lung cancer deaths among women who continue to smoke are attributable to smoking.

- Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is a cause of lung cancer and coronary heart disease among women who are lifetime nonsmokers. Infants born to women exposed to environmental tobacco smoke during pregnancy have a small decrement in birth weight and a slightly increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation compared to infants of nonexposed women.

- Women who stop smoking greatly reduce their risk of dying prematurely, and quitting smoking is beneficial at all ages. Although some clinical intervention studies suggest that women may have more difficulty quitting smoking than men, national survey data show that women are quitting at rates similar to or even higher than those for men. Prevention and cessation interventions are generally of similar effectiveness for women and men and, to date, few gender differences in factors related to smoking initiation and successful quitting have been identified.

- Smoking during pregnancy remains a major public health problem despite increased knowledge of the adverse health effects of smoking during pregnancy. Although the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy has declined steadily in recent years, substantial numbers of pregnant women continue to smoke, and only about one-third of women who stop smoking during pregnancy are still abstinent one year after the delivery.

- Tobacco industry marketing is a factor influencing susceptibility to and initiation of smoking among girls, in the United States and overseas. Myriad examples of tobacco ads and promotions targeted to women indicate that such marketing is dominated by themes of social desirability and independence. These themes are conveyed through ads featuring slim, attractive, athletic models, images very much at odds with the serious health consequences experienced by so many women who smoke.

Prevalence of current smoking among women aged 18 years or older, all women, by education (1998), and by race/ethnicity (1997–1998), United States.

Source: National Health Interview Survey, 1998. Source: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–1998.

Age-adjusted death rates for lung cancer and breast cancer among women, United States, 1930–1997

Note: Death rates are age–adjusted to the 1970 population.

Sources: Parker et al. 1996; National Center for Health Statistics 1999; Ries et al. 2000; American Cancer

Society, unpublished data.

Patterns of Tobacco Use Among Women and Girls

- The prevalence of current smoking among women was 22% in 1998. Smoking prevalence was highest among American Indian or Alaska Native women, intermediate among white women and black women, and lowest among Hispanic women and Asian or Pacific Islander women. By educational level, smoking prevalence is nearly three times higher among women with 9 to 11 years of education than among women with 16 or more years of education.

- Much of the progress in reducing smoking prevalence among girls in the 1970s and 1980s was lost with the increase in prevalence in the 1990s: current smoking among high school senior girls was the same in 2000 as in 1988. Although smoking prevalence was higher among high school senior girls than among high school senior boys in the 1970s and early 1980s, prevalence has been comparable since the mid–1980s.

- Smoking declined substantially among black girls from the mid–1970s through the early 1990s; the decline among white girls for this same period was small.

- Smoking during pregnancy appears to have decreased from 1989 through 1998. Despite increased knowledge of the adverse health effects of smoking during pregnancy, estimates of women smoking during pregnancy range from 12.9% to as high as 22%.

- Since the late 1970s or early 1980s, women are just as likely to attempt to quit and succeed as are men.

- Smoking prevalence among women varies markedly across countries; it is as low as an estimated 7% in developing countries to 24 percent in developed countries. Thwarting further increases in tobacco use among women is one of the greatest disease prevention opportunities in the world today.

Health Consequences of Tobacco Use Among Women

- A woman’s annual risk for death more than doubles among continuing smokers compared with persons who have never smoked in all age groups from 45 through 74 years.

- The risk for lung cancer increases with quantity, duration, and intensity of smoking. The risk for dying of lung cancer is 20 times higher among women who smoke two or more packs of cigarettes per day than among women who do not smoke.

- Smoking is a major cause of cancers of the oropharynx and bladder among women. Evidence is also strong that women who smoke have increased risks for liver, colorectal, and cervical cancer, and cancers of the pancreas and kidney. For cancers of the larynx and esophagus, evidence among women is more limited but consistent with large increases in risk.

- Smoking is a major cause of coronary heart disease among women. Risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked and the duration of smoking. Risk is substantially reduced within 1 or 2 years of smoking cessation. This immediate benefit is followed by a more gradual reduction in risk to that among nonsmokers by 10 to 15 or more years after cessation.

- Women who smoke have an increased risk for stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage. The increased risk for stroke associated with smoking is reversible after smoking cessation; after 5 to 15 years of abstinence, the risk approaches that of women who have never smoked.

- Women who smoke have an increased risk for death from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. They also have risk for peripheral vascular atherosclerosis, but cessation is associated with improvements in symptoms, prognosis, and survival. Smoking is also a strong predictor of the progression and severity of carotid atherosclerosis among women, but smoking cessation appears to slow the rate of progression.

- Cigarette smoking is a primary cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among women, and the risk increases with the amount and duration of smoking. Approximately 90% of deaths from COPD among women in the United States can be attributed to cigarette smoking.

- Adolescent girls who smoke have reduced rates of lung growth, and adult women who smoke experience a premature decline of lung function.

- Women who smoke have increased risks for conception delay and for both primary and secondary infertility and may have a modest increase in risks for ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. They are younger at natural menopause than non–smokers and may experience more menopausal symptoms.

- Women who quit smoking before or during pregnancy reduce the risk for adverse reproductive outcomes, including conception delay, infertility, preterm premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.

- Postmenopausal women who currently smoke have lower bone density than do women who do not smoke. Also women who currently smoke have an increased risk for hip fracture compared with nonsmoking women.

- The association of smoking and depression is particularly important among women because they are more likely to be diagnosed with depression than are men.

- Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is a cause of lung cancer among women who have never smoked and is associated with increased coronary heart disease risk.

Factors Influencing Tobacco Use Among Women

- Girls who initiate smoking are more likely than those who do not smoke to have parents or friends who smoke. They also tend to have weaker attachments to parents and family and stronger attachments to peers and friends. They perceive smoking prevalence to be higher than it actually is, are inclined to risk taking and rebelliousness, have a weaker commitment to school or religion, have less knowledge of the adverse consequences of smoking and the addictiveness of nicotine, believe that smoking can control weight and negative moods, and have a positive image of smokers.

- Women who continue to smoke and those who fail at attempts to stop smoking tend to have lower education and employment levels than do women who quit smoking. They also tend to be more addicted to cigarettes, as evidenced by the smoking of a higher number of cigarettes per day, to be cognitively less ready to stop smoking, to have less social support for stopping, and to be less confident in resisting temptations to smoke.

- Women have been extensively targeted in tobacco marketing, and tobacco companies have produced brands specifically for women, both in the United States and overseas. Myriad examples of tobacco ads and promotions targeted to women indicated that such marketing is dominated by themes of both social desirability and independence, which are conveyed through ads featuring slim, attractive, athletic models. Between 1995 and 1998, expenditures for domestic cigarette advertising and promotion increased from $4.90 billion to $6.73 billion. Tobacco industry marketing, including product design, advertising, and promotional activities, is a factor influencing susceptibility to and initiation of smoking.

- The dependence of the media on revenues from tobacco advertising oriented to women, coupled with tobacco company sponsorship of women’s fashions and of artistic, athletic, political, and other events, has tended to stifle media coverage of the health consequences of smoking among women and to mute criticism of the tobacco industry by women public figures.

Efforts to Reduce Tobacco Use Among Women

- Using evidence from studies that vary in design, sample characteristics, and intensity of the interventions studied, researchers to date have not found consistent gender–specific differences in the effectiveness of intervention programs for tobacco use.

- A higher percentage of women stop smoking during pregnancy, both spontaneously and with assistance, than at other times in their lives. Using pregnancy–specific programs can increase smoking cessation rates, which benefits infant health and is cost effective. Only about one–third of women who stop smoking during pregnancy are still abstinent one year after the delivery.

- Successful interventions have been developed to prevent smoking among young people, but little systematic effort has been focused on developing and evaluating prevention interventions specifically for girls.

- There are numerous effective smoking cessation methods available in the United States. The methods range from self-help materials, to intensive clinical approaches, to broad community-based programs. Minimal clinical assistance; intensive clinical assistance; and individual, group, or telephone counseling have shown few differences in effectiveness between men and women.

- Studies show no major or consistent differences between women’s and men’s motivation to quit, readiness to quit, general awareness of the harmful health effects of smoking, or the effectiveness of intervention programs for tobacco use.

- Based on national surveys, the probability of attempting to quit smoking and to succeed has been equally high among women and men since the late 1970s or early 1980s.

- The majority of smokers who try to stop using tobacco reported doing so on their own, even though this is the least effective method. This pattern has changed somewhat in recent years with increased use of pharmacologic aids.

- The likelihood of having been counseled to stop smoking was slightly higher for women (39%) than for men (35%); women report more physician visits than men, which allows more opportunity for counseling.

- Intensive clinical interventions involve individual, group, or telephone counseling for multiple sessions. The most successful treatments are multi-component cognitive behavioral programs that incorporate strategies to prepare and motivate smokers to stop smoking.

- Women are somewhat more likely than men to use intensive treatment programs. Similarly, women have a stronger interest than men in smoking cessation groups that offer mutual support through a buddy system and in treatment meetings over a long period.

- A number of effective pharmacotherapies for nicotine addiction have emerged in the past decade—nicotine gum and nicotine patch (approved for over-the-counter use), nicotine nasal spray, oral nicotine inhaler, and Bupropion (available by prescription). Two other pharmacotherapies, Clonidine and the antidepressant Nortiptyline, have been recommended as second-line pharmacotherapies, but have not yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication—smoking cessation.

- Pharmacologic approaches to smoking cessation raise a number of issues specific to women. Nevertheless, nicotine replacement has been shown to be more effective than placebo among women smokers and, thus, remains recommended for use.

- More research is needed to determine the effects of nicotine replacement therapy on pregnant women and their offspring.

- Studies have identified numerous gender-related factors that should be studied as predictors for smoking cessation as well as factors for continued smoking or relapse after quitting. These factors include hormonal influences, pregnancy, fear of weight gain, lack of social support, and depression.

- Women stop smoking more often during pregnancy—both spontaneously and with assistance—than at any other time in their lives. However, most women return to smoking after pregnancy: up to 67% are smoking again by 12 months after delivery.

- Pregnancy-specific programs benefit both maternal and infant health and are cost-effective. If the national prevalence of smoking before or during the first trimester of pregnancy were reduced by one percentage point annually, it would prevent 1,300 babies from being born at low birth weight and save $21 million (in 1995 dollars) in direct medical costs in the first year alone. Prenatal smoking cessation interventions can be of economic benefit to healthcare insurers.

- More women than men fear weight gain if they quit smoking; however, few studies have found a relationship between weight gain concerns and smoking cessation among either women or men. Further, actual weight gain during cessation efforts does not predict relapse to smoking.

- Smoking cessation treatment and social support derived from family and friends improve cessation rates. Whether there are gender differences in the role of social support on long-term smoking cessation is inconclusive.

- Women of low socioeconomic status (SES) have lower rates of smoking cessation than do women of higher SES. Studies that analyze the effects of mass media campaigns suggest that smokers of low SES, especially women, are more likely than smokers of high SES to watch and obtain cessation information from television.

- Women of low SES enrolled in intensive cessation intervention programs (stress management, self-esteem enhancement, group support, and other activities that improve quality of life) have 20%–25% successful cessation rates. Unfortunately, only a small proportion of women of low SES appear to take advantage of these programs.

- In general, African-American, Hispanic, and American-Indian or Alaska-Native women want to stop smoking at rates similar to those of white women, but there is little research on smoking cessation among women in racial/ethnic minority populations.

- There is strong scientific evidence that shows increases in state and federal excise taxes on tobacco products reduce consumption and increase the number of people who stop using tobacco. Price increases reduce consumption of tobacco products by adults, young adults, adolescents, and children.

- Mass-media campaigns implemented in combination with other interventions, such as excise tax increases and community education programs, are effective in reducing tobacco consumption and motivating tobacco product users to quit.

- There are a number of effective interventions to help tobacco users in their efforts to quit, such as behavioral programs offering counseling in individual or group settings and the use of a number of pharmacotherapies, including nicotine replacement. One way to increase the use of effective treatments is to lower the cost for people who wish to use these treatments. Scientific evidence shows that interventions that reduce smokers’ costs (such as programs that reduce or eliminate the insured’s copayment) increase the number of people who stop using tobacco products.

- There is no Medicare coverage for tobacco use dependence except in a few states that will participate in a demonstration project starting in April 2001.

- Six states provide Medicaid coverage for counseling, and four states cover all prescription drugs and over-the-counter nicotine replacement products.

- Under private insurance, 42% of managed care organizations (MCOs) cover counseling, 16% cover indemnity counseling, 38% cover drugs, and 25% cover indemnity drugs.

Mortality

- Cigarette smoking plays a major role in the mortality of U.S. women. Since 1980, when the Surgeon General’s Report on Women and Smoking was released, about three million women have died prematurely of smoking-related diseases.

- In 1997, about 165,000 U.S. women died of smoking-related diseases, including lung and other cancers, heart disease, stroke, and chronic lung diseases such as emphysema.

- Each year throughout the 1990s, about 2.1 million years of the potential life of U.S. women were lost prematurely because of smoking-attributable diseases. Women smokers who die of a smoking-related disease lose on average 14 years of potential life.

- Women who stop smoking greatly reduce their risk of dying prematurely. The relative benefits of smoking cessation are greater when women stop smoking at younger ages, but smoking cessation is beneficial at all ages.

Lung Cancer

- Cigarette smoking is the major cause of lung cancer among women. About 90% of all lung cancer deaths among U.S. women smokers are attributable to smoking.

- In 1950, lung cancer accounted for only 3% of all cancer deaths among women; however, by 2000, it accounted for an estimated 25% of cancer deaths.

- Since 1950, lung cancer mortality rates for U.S. women have increased an estimated 600%. In 1987, lung cancer surpassed breast cancer to become the leading cause of cancer death among U.S. women. In 2000, about 27,000 more women died of lung cancer (67,600) than breast cancer (40,800).

Other Cancers

- Smoking is a major cause of cancer of the oropharynx and bladder among women. Evidence is also strong that women who smoke have increased risk for cancer of the pancreas and kidney. For cancer of the larynx and esophagus, evidence that smoking increases the risk among women is more limited but consistent with large increases in risk.

- Women who smoke may have a higher risk for liver cancer and colorectal cancer than women who do not smoke.

- Smoking is consistently associated with an increased risk for cervical cancer. The extent to which this association is independent of human papillomavirus (tumor caused by virus) infection is uncertain.

- Several studies suggest that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is associated with an increased risk for breast cancer; however, this association remains uncertain. More research is needed.

Cardiovascular Disease

- Smoking is a major cause of coronary heart disease among women. Risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked and the duration of smoking.

- Women who smoke have an increased risk for ischemic stroke (blood clot in one of the arteries supplying the brain) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding in the area surrounding the brain).

- Women who smoke have an increased risk for peripheral vascular atherosclerosis.

- Smoking cessation reduces the excess risk of coronary heart disease, no matter at what age women stop smoking. The risk is substantially reduced within 1 or 2 years after they stop smoking.

- The increased risk for stroke associated with smoking begins to reverse after women stop smoking. About 10 to 15 years after stopping, the risk for stroke approaches that of a women who never smoked.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Lung Function

- Cigarette smoking is the primary cause of COPD in women, and the risk increases with the amount and duration of cigarette use.

- Mortality rates for COPD have increased among women for the past 20 to 30 years. About 90% of mortality from COPD among U.S. women is attributed to smoking.

- Exposure to maternal smoking is associated with reduced lung function among infants, and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke during childhood and adolescence may be associated with impaired lung function among girls.

- Smoking by girls can reduce their rate of lung growth and the level of maximum lung function. Women who smoke may experience a premature decline of lung function.

Menstrual Function

- Some studies suggest that cigarette smoking may alter menstrual function by increasing the risks for painful menstruation, secondary amenorrhea (abnormal absence of menstrual), and menstrual irregularity

- Women smokers have natural menopause at a younger age than do nonsmokers, and they may experience more severe menopausal symptoms.

Reproductive Outcomes

- Women who smoke have increased risk for conception delay and for both primary and secondary infertility.

- Women who smoke during pregnancy risk pregnancy complications, premature birth, low-birth-weight infants, stillbirth, and infant mortality.

- Women who smoke may have a modest increase in risks for ectopic pregnancy (fallopian tube or peritoneal cavity pregnancy) and spontaneous abortion.

- Studies show a link between smoking and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) among the offspring of women who smoke during pregnancy.

Bone Density and Fracture Risk

- Postmenopausal women who smoke have lower bone density than women who never smoked.

- Women who smoke have an increased risk for hip fracture than women who never smoked.

Other Conditions

- Women who smoke may have a modestly elevated risk for rheumatoid arthritis.

- Women smokers have an increased risk for cataract, and may have an increased risk for age-related macular degeneration.

- The prevalence of smoking generally is higher for women with anxiety disorders, bulimia, depression, attention deficit disorder, and alcoholism; it is particularly high among patients with diagnosed schizophrenia. The connection between smoking and these disorders requires additional research.

Health Consequences of Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS)

- Exposure to ETS is a cause of lung cancer among women nonsmokers.

- Studies support a causal relationship between exposure to ETS and coronary heart disease mortality among women nonsmokers.

- Infants born to women who are exposed to ETS during pregnancy may have a small decrement in birth weight and a slightly increased risk for intrauterine growth retardation.

- Tobacco advertising geared toward women began in the 1920s. By the mid-1930s, cigarette advertisements targeting women were becoming so commonplace that one advertisement for the mentholated Spud brand had the caption “To read the advertisements these days, a fellow’d think the pretty girls do all the smoking.”

- As early as the 1920s, tobacco advertising geared toward women included messages such as “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” to establish an association between smoking and slimness. The positioning of Lucky Strike as an aid to weight control led to a greater than 300% increase in sales for this brand in the first year of the advertising campaign.

- Through World War II, Chesterfield advertisements regularly featured glamour photographs of a Chesterfield girl of the month, usually a fashion model or a Hollywood star such as Rita Hayworth, Rosalind Russell, or Betty Grable.

- The number of women aged 18 through 25 years who began smoking increased significantly in the mid-1920s, the same time that the tobacco industry mounted the Chesterfield and Lucky Strike campaigns directed at women. The trend was most striking among women aged 18 though 21. The number of women in this age group who began smoking tripled between 1911 and 1925 and had more than tripled again by 1939.

- In 1968, Philip Morris marketed Virginia Slims cigarettes to women with an advertising strategy showing canny insight into the importance of the emerging women’s movement. The slogan “You’ve come a long way, Baby” later gave way to “It’s a woman thing” in the mid-1990s, and more recently the “Find your voice” campaign featuring women of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The underlying message of these campaigns has been that smoking is related to women’s freedom, emancipation, and empowerment.

- Initiation rates among girls aged 14 though 17 years rapidly increased in parallel with the combined sales of the leading women’s-niche brands (Virginia Slims, Silva Thins, and Eve) during this period.

- In 1960, about 10% of all cigarette advertisements appeared in popular women’s magazines, and by 1985, cigarette advertisements increased by 34%.

- Women have been extensively targeted in tobacco marketing. Such marketing is dominated by themes of an association between social desirability, independence, and smoking messages conveyed through advertisements featuring slim, attractive, and athletic models. In 1999, expenditures for domestic cigarette advertising and promotion was $8.24 billion—increasing 22.3 % from the $6.73 billion spent in 1998.

- Advertising is used in part to reduce women’s fear of the health risks from smoking by presenting information on nicotine and tar content or by using positive images (e.g., models engaged in exercise or pictures of white capped mountains against a background of clear blue skies).

- Because cigarette brands developed exclusively for women (e.g., Virginia Slims, Eve, Misty, and Capri) account for only 5% to 10% of the cigarette market. Many women are also attracted to brands that appear gender neutral or overtly targeted to males.

- Research has shown that women’s magazines that accept tobacco advertising are significantly less likely to publish articles critical of smoking than are magazines that do not accept such advertising.

- The tobacco industry has targeted women through innovative promotional campaigns offering discounts on common household items unrelated to tobacco. For example, Philip Morris has offered discounts on turkeys, milk, soft drinks, and laundry detergent with the purchase of tobacco products.

- Cigarette brand clothing and other giveaway accessories have been use to promote cigarettes products to women and girls.

- Virginia Slims offered a yearly engagement calendar and the V-Wear catalog featuring clothing, jewelry, and accessories coordinated with the themes and colors of the print advertising and product packaging.

- Capri Superslims used point-of-sale displays and value-added gifts featuring items such as mugs and caps bearing the Capri label in colors coordinated with the advertisement and package.

- Misty Slims offered color-coordinated items in multiple-pack containers. The manufacturer also offered an address book, cigarette lighter, T-shirt, and fashion booklet.

- Evidence suggests a pattern of international tobacco advertising that associates smoking with success, similar to that seen in the United States. This development emphasizes the enormous potential of advertising to change social norms.

- As western-styled marketing has increased, campaigns commonly have focused on women. For example, in 1989, the brand Yves Saint Laurent introduced a new elegant package designed to appeal to women in Malaysia and other Asian countries. National tobacco monopolies and companies, such as those in Indonesia and Japan, began to copy this promotional targeting of women.

- One of the most popular media for reaching women—particularly in places where tobacco advertising is banned on television – is women’s magazines. Magazines can lend an air of social acceptability or stylish image to smoking. This may be particularly important in countries where smoking rates are low among women and where tobacco companies are attempting to associate smoking with Western values.

- A study of 111 women’s magazines in 17 European countries in 1996-1997 found that 55% of the magazines that responded accepted cigarette advertisements, and only 4 had a policy of voluntarily refusing it. Only 31% of the magazines had published an article of one page or more on smoking and health in the previous 12 months. Magazines that accepted tobacco advertisements seem less likely to give coverage to smoking and health issues.

- One of the most common advertisement themes in developed countries is that smoking is both a passport to and a symbol of the independence and success of the modern women.

- Events and activities popular among young people are often sponsored by tobacco companies. Free tickets to films and to pop and rock concerts have been given in exchange for empty cigarette packets in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Popular U.S. female stars have allowed their names to be associated with cigarettes in other countries.

- Many countries have banned tobacco advertising and promotion. In 1998, the European Union adopted a directive to ban most tobacco advertising and sponsorship by July 30, 2006. Other countries have banned direct advertising, and still others have instituted partial restraints. Such bans are often circumvented by tobacco companies through various promotional venues such as the creation of retail stores named after cigarette brands or corporate sponsorship of sporting and other events. Moreover, national bans on tobacco advertisements may be rendered ineffective by tobacco promotion on satellite television, by cable broadcasting, or via the Internet.

- Cigarette smoking was rare among women in the early 20th century. Cigarette smoking became prevalent among women after it did among men, and smoking prevalence has always been lower among women than among men. However, the gender-specific difference in smoking prevalence narrowed between 1965 and 1985. Since 1985, the decline in prevalence among men and women has been comparable.

- Smoking prevalence decreased among women, from 33.9% in 1965 to 22.0% in 1998. Most of this decline occurred from 1974 through 1990; prevalence declined very little from 1992 through 1998.

- The prevalence of current smoking is three times higher among women with 9–11 years of education (32.9%) than among women with 16 or more years of education (11.2%).

- Smoking prevalence is higher among women living below the poverty level (29.6%) than among those living at or above the poverty level (21.6%).

- In 1997–1998, 34.5% of American-Indian or Alaska-Native, 23.5% of white, 21.9% of African-American, 13.8% of Hispanic, and 11.2% Asian/Pacific-Islander women were current smokers.

- Among white women and African-American women, smoking prevalence decreased from 1965 through 1998. The prevalence of current smoking was generally comparable, but from 1970 through 1985 it was higher—some years significantly so—among African-American women. In 1990, it was higher among white women.

- From 1965 through 1998, the decline in smoking prevalence among Hispanic women was significantly less than among white and African-American women.

- Among Asian-American or Pacific-Islander women, smoking prevalence decreased from 1979 through 1992, but then increased from 1995 through 1998. Prevalence changed little from 1979 through 1998 among American-Indian or Alaska-Native women.

- Among high school senior girls, past-month current smoking rates decreased from 39.9% in 1977 to 25.8% in 1992, but increased to 35.3% during 1997. In 2000, smoking prevalence declined again to 29.7%.

- Much of the progress in reducing smoking prevalence among girls in the 1970s and 1980s was lost with the increase in prevalence in the 1990s. Current smoking rates among high school senior girls were the same in 2000 as in 1988.

- In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the prevalence of smoking among high school seniors was higher among girls than among boys, but the decline in smoking prevalence from 1976 through 1992 was more rapid among girls than among boys. Since the mid 1980s, smoking prevalence among girls and boys has been similar.

- From 1991 to 1996, current smoking prevalence in the past 30 days increased from 13.1% to 21.1% among 8th-grade girls but decreased to 14.7% in 2000. Among 10th-grade girls, current smoking prevalence in the past 30 days increased from 20.7% in 1991 to 31.1% in 1997 but decreased to 23.6% in 2000.

- Aggregated data from 1976–1977 through 1991–1992 showed a dramatic decline in past-month cigarette smoking among African-American high school senior girls (from 37.5% to 7.0%) compared with the decline among white girls (from 39.9% to 31.2%). From 1991–1992 through 1997–1998, past-month smoking prevalence increased among white girls (from 31.2% to 41.0%) and African-American girls (from 7.0% to 12.0%)—but the increase was statistically significant only among white girls.

- In 1990–1994, smoking prevalence for high-school senior girls was highest among American Indians or Alaska Natives (39.4%) and whites (33.1%) and lowest among Hispanics (19.2%), Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders (13.8%), and African Americans (8.6%).

- Smoking among young women (aged 18 through 24 years) declined from 37.3% in 1965–1966 to 25.1% in 1997–1998. However, recent trends show that smoking rates in this population may be rising.

- In 1998, nearly 14 million women of reproductive age were smokers, and smoking prevalence in this group was higher (25.3%) than in the overall population of women aged 18 years or older (22.0%).

- Despite increased knowledge of the adverse health effects of smoking during pregnancy, survey data suggest that a substantial number of pregnant women and girls smoke. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy declined from 19.5% in 1989 to 12.9% in 1998.

- Smoking prevalence during pregnancy differs by age and by race and ethnicity. In 1998, smoking prevalence during pregnancy was consistently highest among young adult women aged 18 through 24 years (17.1%) and lowest among women aged 25 through 49 years (10.5%).

- Smoking during pregnancy declined among women of all racial/ethnic populations. From 1989 to 1998, smoking among American-Indian or Alaska-Native pregnant women decreased from 23.0% to 20.2%; among pregnant white women from 21.7% to 16.2%; African-American pregnant women from 17.2% to 9.6%; Hispanic pregnant women from 8.0% to 4.0%; and Asian-American or Pacific-Islander pregnant women from 5.7% to 3.1%.

- In 1998, there was nearly a twelvefold difference among pregnant women who smoke—ranging from 25.5% among mothers with 9–11 years of education to 2.2% among mothers with 16 or more years of education.

- The level of nicotine dependence is strongly associated with the quantity of cigarettes smoked per day.

- When results are stratified by the number of cigarettes smoked per day, girls and women who smoke appear to be equally dependent on nicotine, as measured by first cigarette after waking, smoking for a calming and relaxing effect, withdrawal symptoms, or other measures of nicotine dependence.

- Of the women who smoke, more than three-fourths report one or more indicators of nicotine dependence, and nearly three-fourths report feeling dependent on cigarettes.

- More than three-fourths (75.2%) of women want to quit smoking completely, and nearly half (46.6%) report having tried to quit during the previous year.

- In 1998, the percentage of people who had ever smoked and who had quit was lower among women (46.2%) than among men (50.9%). This finding may be because men began to stop smoking earlier in the 20th century than did women and because these data do not take into account that men are more likely than women to switch to, or to continue to use, other tobacco products when they stop smoking.

- Since the late 1970s or early 1980s, the probability of attempting to quit smoking and succeeding has been equal among women and men.

- The use of cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco among women is generally low, but recent data suggest that cigar smoking among women and girls is increasing.

- A California study found that current cigar smoking among women increased fivefold from 1990 through 1996.

- The prevalence of cigar use appears to be higher among adolescent girls than among women. In 1999, past-month cigar use among high school girls younger than 18 years was 9.8%.

- The prevalence of pipe smoking among women is low, and women are much less likely than men to smoke a pipe.

- The prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among girls and women is low and remains considerably lower than that among boys and men.

- For tobacco use other than cigarettes among high school girls, cigar use is the most common, bidi and kretek use are intermediate, and pipe and smokeless tobacco use are the least common.

- Women smokers, like men smokers, are at increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease, but women smokers also experience unique risks related to menstrual and reproductive function.

- Women who smoke have increased risk conception delay and for primary and secondary infertility.

- Women who smoke may have a modest increase in risks for ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion.

- Smoking during pregnancy is associated with increased risk for premature rupture of membranes, abruptio placentae (placenta separation from the uterus), and placenta previal (abnormal location of the placenta, which can cause massive hemorrhaging during delivery; smoking is also associated with a modest increase in risk for preterm delivery.

- Infants born to women who smoke during pregnancy have a lower average birth weight and are more likely to be small for gestational age than infants born to women who do not smoke. Low birth weight is associated with increased risk for neonatal, perinatal, and infant morbidity and mortality. The longer the mother smokes during pregnancy, the greater the effect on the infant’s birth weight.

- The risk for perinatal mortality, both stillbirths and neonatal deaths, and the risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are higher for the offspring of women who smoke during pregnancy.

- Women who smoke are less likely to breast-feed their infants than are women who do not.

- Infants born to women who are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) during pregnancy may have a small decrement in birth weight and a slightly increased risk for intrauterine growth retardation than infants born to women who are not exposed to ETS.

- Despite increased knowledge of the adverse health effects of smoking during pregnancy, estimates of women smoking during pregnancy range from 12% (based on birth certificate data) up to 22% (based on survey data). However, smoking during pregnancy appears to have decreased from 1989 through 1998.

- Eliminating maternal smoking may lead to a 10% reduction in all infant deaths and a 12% reduction in deaths from perinatal conditions.

- Women who quit smoking before or during pregnancy reduce the risk for adverse reproductive outcomes, including difficulties in becoming pregnant, infertility, premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.

- Most relevant studies suggest that infants of women who stop smoking by the first trimester have weight and body measurements comparable with those of nonsmokers’ infants. Studies also suggest that smoking in the third trimester is particularly detrimental.

- Women are more likely to stop smoking during pregnancy, both spontaneously and with assistance, than at other times in their lives. Using pregnancy-specific programs can increase smoking cessation rates, which benefits infant health and is cost effective. However, only one-third of women who stop smoking during pregnancy are still abstinent 1 year after the delivery.

- Programs that encourage women to stop smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—and not to take up smoking ever again—deserve high priority for two reasons: during pregnancy women are highly motivated to stop smoking, and they still have many remaining years of potential life.

Increase awareness of the devastating impact of smoking on women’s health. Smoking is the leading known cause of preventable death and disease among women

In 1997, smoking accounted for about 165,000 deaths among U.S. women. In 1987, lung cancer became the leading cause of cancer death among women, and by 2000, about 27,000 more women in the United States died of lung cancer (about 68,000) than of breast cancer (about 41,000).

Expose and counter the tobacco industry’s deliberate targeting of women and decry its efforts to link smoking, which is so harmful to women’s health, with women’s rights and progress in society

In 1999 tobacco companies spent more than $8.24 billion,— or more than $22.6 million a day—to advertise and promote cigarettes. To sell its products, the tobacco industry exploits themes of success and independence, particularly in its advertising in women’s magazines.

Encourage a more vocal constituency on issues related to women and smoking

Taking a lesson from the success of advocacy to reduce breast cancer, we must make concerted efforts to call public attention to the toll of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases on women’s health. Women affected by tobacco-related diseases and their families and friends can partner with women’s and girls’ organizations, women’s magazines, female celebrities, and others—not only in an effort to raise awareness of tobacco-related disease as a women’s issue, but also to call for policies and programs that deglamorize and discourage tobacco use.

Recognize that nonsmoking is by far the norm among women

Publicize that most women are nonsmokers. Nearly four-fifths of U.S. women are nonsmokers, and in some subgroup populations, smoking is relatively rare (e.g., only 11.2 % of women who have completed college are current smokers, and only 5.4 % of black high school seniors girls are daily smokers). It important to recognize that among adult women those who are most empowered, as measured by educational attainment, are the least likely to be smokers. Moreover, most women who smoke want to quit.

Conduct further studies of the relationship between smoking and certain outcomes of importance to women’s health

Additional research is needed to explore these issues:

- The link between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and the risk of breast cancer.

- Cigarette brand variations in toxicity and whether any of these possible variations may be related to changes in lung cancer histology during the past decade.

- Changes in tobacco products and whether increased exposure to tobacco-specific nitrosamines may be related to the increased incidence rates of adenocarcinoma (malignant glandular tumor) of the lung.

- Health effects of smoking among women in the developing world.

Encourage the reporting of gender-specific results from studies of influences on smoking behavior, smoking prevention and cessation interventions, and the health effects of tobacco use, including use of new tobacco products

Research is needed to better understand and to reduce current disparities in smoking prevalence among women of different groups as defined by socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Women with only 9 to 11 years of education are about three times as likely to be smokers as are women with a college education. American Indian or Alaska Native women are much more likely to smoke than are Hispanic women and Asian or Pacific Islander women. Among teenage girls, white girls are much more likely to smoke than are African American girls.

Determine why, during most of the 1990s, smoking prevalence declined so little among women and increased so markedly among teenage girls

This lack of progress is a major concern and threatens to prolong the epidemic of smoking-related diseases among women. More research is needed to determine the influences that encourage many women and girls to smoke even in the face that all that is known of the dire health consequence of smoking. If, for example, smoking in movies by female celebrities promotes smoking, then discouraging such practices as well as engaging well-known actresses to be spokespersons on the issue of women and smoking should be a high priority.

Develop a research and evaluation agenda related to women and smoking

Research agendas should focus on these issues:

- Determining whether gender-tailored interventions increase the effectiveness of various smoking prevention and cessation methods.

- Documenting whether there are gender differences in the effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments for tobacco cessation.

- Determining which tobacco prevention and cessation interventions are most effective for specific subgroups of girls and women.

- Designing interventions to reduce disparities in smoking prevalence across all subgroups of girls and women.

Support efforts, at both individual and societal levels, to reduce smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke among women.

Tobacco-use treatments are among the most cost-effective of preventive health interventions at the individual level, and they should be part of all women’s health care programs. Health insurance plans should cover such services. Societal strategies to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke include counteradvertising, increasing tobacco taxes, enacting laws to reduce minors’ access to tobacco products, and banning smoking in work sites and in public places.

Enact comprehensive statewide tobacco control programs proven to be effective in reducing and preventing tobacco use

Results from states such as Arizona, California, Florida, Maine, Massachusetts, and Oregon show that science-based tobacco control programs have successfully reduced smoking rates among women and girls. California established a comprehensive statewide tobacco control program more than 10 years ago, and is now starting to observe the benefits of its sustained efforts. Between 1988 and 1997, the incidence rate of lung cancer among women declined by 4.8% in California but increased by 13.2% in other regions of the United States.

Increase efforts to stop the emerging epidemic of smoking among women in developing countries

Strongly encourage and support multinational policies that discourage the spread of smoking and tobacco-related diseases among women in countries where smoking prevalence has traditionally been low. It is urgent that what is already known about effective means of tobacco control at the societal level be disseminated throughout the world.

Support the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC)

The FCTC is an international legal instrument designed to curb the global spread of tobacco use through specific protocols–currently being negotiated–that relate to tobacco pricing, smuggling, advertising, sponsorship, and other activities.

Disclaimer: Data and findings provided in the publications on this page reflect the content of this particular Surgeon General’s Report. More recent information may exist elsewhere on the Smoking & Tobacco Use Web site (for example, in fact sheets, frequently asked questions, or other materials that are reviewed on a regular basis and updated accordingly).