Vital Signs: Opioid Prescribing

Where you live matters

Despite recent declines, opioid prescribing is still high and inconsistent across the US.

The amount of opioids prescribed per person was three times higher in 2015 than in 1999.

180 MME 640 MME

1999 | US 2015 | US

Sources: Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) of the Drug Enforcement Administration; 1999. QuintilesIMS Transactional Data Warehouse; 2015.

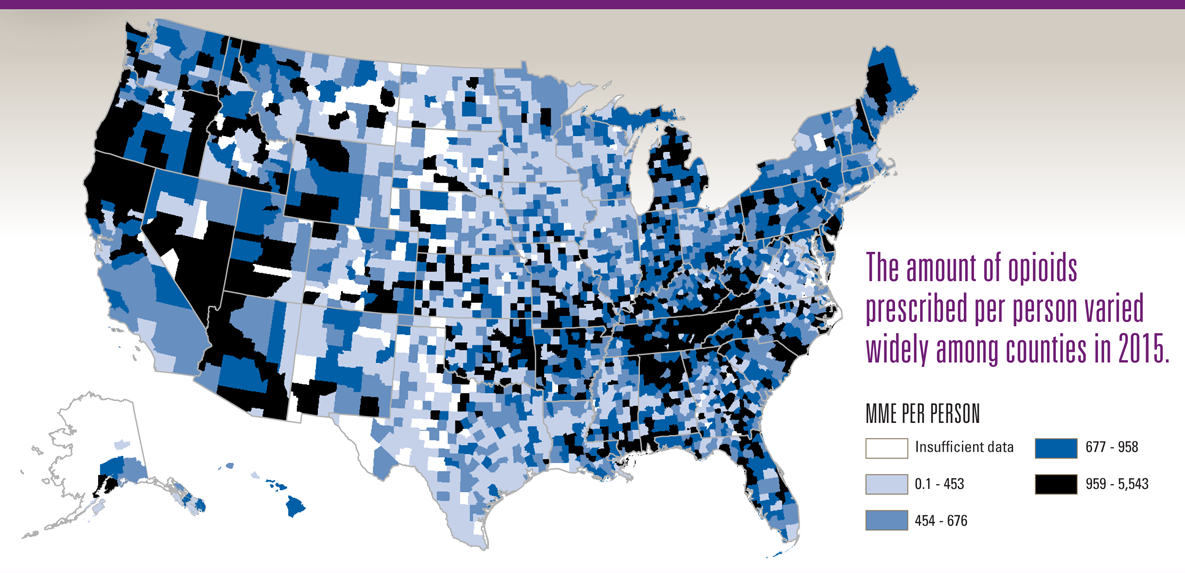

The amount of opioids prescribed per person varied widely among counties in 2015.

MME per person

Insufficient data

0.1 – 453

454 – 676

677 – 958

959 – 5,543

Higher opioid prescribing puts patients at risk for addiction and overdose. The wide variation among counties suggests a lack of consistency among providers when prescribing opioids. The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain offers recommendations that may help to improve prescribing practices and ensure all patients receive safer, more effective pain treatment.

SOURCE: CDC Vital Signs, July 2017

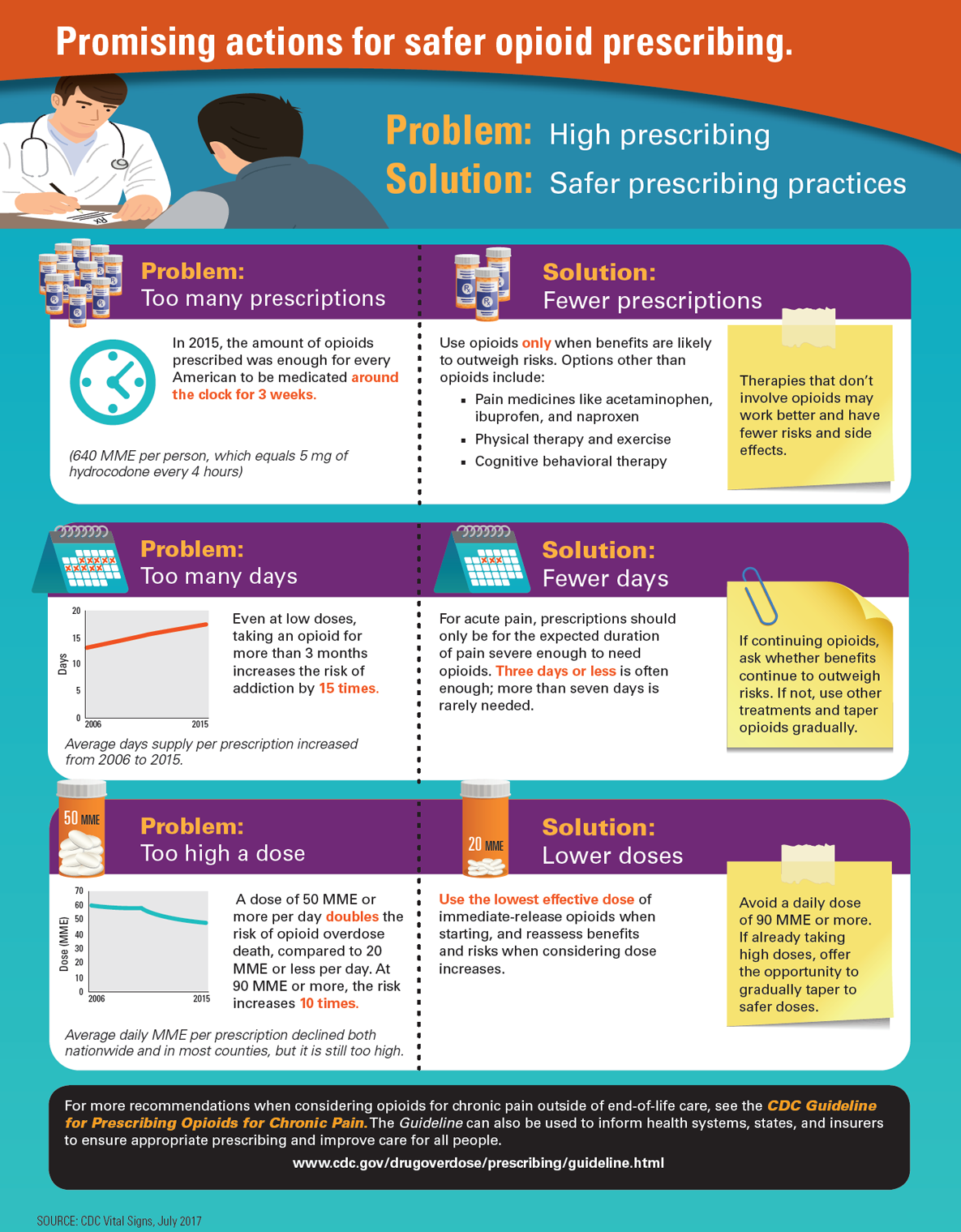

Promising actions for safer opioid prescribing

Problem: High prescribing

Solution: Safer prescribing practices

Problem: Too many prescriptions

In 2015, the amount of opioids prescribed was enough for every American to be medicated around the clock for 3 weeks.

(640 MME per person, which equals 5 mg of hydrocodone every 4 hours)

Solution: Fewer prescriptions

Use opioids only when benefits are likely to outweigh risks. Options other than opioids include:

Pain medicines like acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and naproxen

Physical therapy and exercise

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Therapies that don’t involve opioids may work better and have fewer risks and side effects.

Problem: Too many days

Even at low doses, taking an opioid for more than 3 months increases the risk of addiction by 15 times.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Day Supply Per Prescription | 13.3 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 15.5 | 16.0 | 16.4 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.7 |

For acute pain, prescriptions should only be for the expected duration of pain severe enough to need opioids. Three days or less is often enough; more than seven days is rarely needed.

If continuing opioids, ask whether benefits continue to outweigh risks. If not, use other treatments and taper opioids gradually.

Problem: Too high a dose

A dose of 50 MME or more per day doubles the risk of opioid overdose death, compared to 20 MME or less per day. At 90 MME or more, the risk increases 10 times.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Daily MME Per Prescription | 59.7 | 59.1 | 58.7 | 58.1 | 58.0 | 53.9 | 51.8 | 50.2 | 48.9 | 48.1 |

Use the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids when starting, and reassess benefits and risks when considering dose increases.

Avoid a daily dose of 90 MME or more. If already taking high doses, offer the opportunity to gradually taper to safer doses.

For more recommendations when considering opioids for chronic pain outside of end-of-life care, see The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. The Guideline can also be used to inform health systems, states, and insurers to ensure appropriate prescribing and improve care for all people.

www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

SOURCE: CDC Vital Signs, July 2017