Antibiotic Resistance

Most people with Campylobacter infection don’t need antibiotics. They should drink plenty of fluids while diarrhea lasts.

Some people with serious illness or at risk of serious illness might need antibiotics, such as azithromycin and ciprofloxacin.

However, some bacteria are resistant to these antibiotics commonly used to treat Campylobacter infection. Infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria can be harder to treat, can last longer, and may result in more severe illness.

Thus, these infections can lead to greater healthcare costs and are a serious threat to public health.

How does antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter spread to people?

See a Summary >

Read the Report > [PDF – 148 pages]

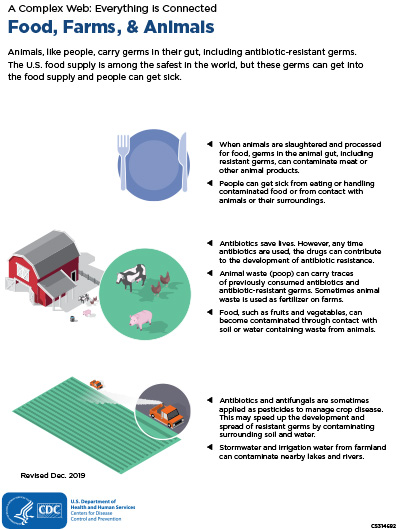

In 1986, fluoroquinolones were approved for use in humans. Ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, is used to treat many kinds of infections (including those caused by Campylobacter). In 1990, a CDC survey in selected U.S. counties showed no ciprofloxacin resistance among a sample of C. jejuni isolates from sick people. In 1995 and 1996, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved fluoroquinolones for use in poultry flocks to control certain infections. In 1997, CDC began Campylobacter surveillance in the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS). NARMS data show that among C. jejuni isolates from U.S. residents, ciprofloxacin resistance increased from 17% in 1997–1999 to 27% in 2015–2017.

FDA withdrew one fluoroquinolone approval for poultry in 2001 and the other in 2005 because of evidence that the use of fluoroquinolones in poultry led to an increase in fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter infections in people. The antibiotic resistance rate did not decrease after the drug was withdrawn from use in poultry. One reason may be that many resistant infections are linked to international travel. A second reason is that fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter seem just as able to survive and multiply in poultry as do the susceptible Campylobacter.

The high rates of resistance to fluoroquinolones have limited their usefulness in treating Campylobacter infections. Macrolides like azithromycin are the current drugs of choice when antibiotic treatment is indicated. Resistance to macrolides in Campylobacter has remained stable. In 2017, 28% of C. jejuni and 38% of C. coli isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin, and 3% of C. jejuni and 7% of C. coli isolates were resistant to the macrolide azithromycin.

Key measures to prevent resistant Campylobacter infections include:

- Using antibiotics appropriately in people and animals

- Improving sanitation on poultry farms and in the pet industry to reduce the spread of Campylobacter

- Implementing disease prevention programs on farms to reduce the need for antibiotics

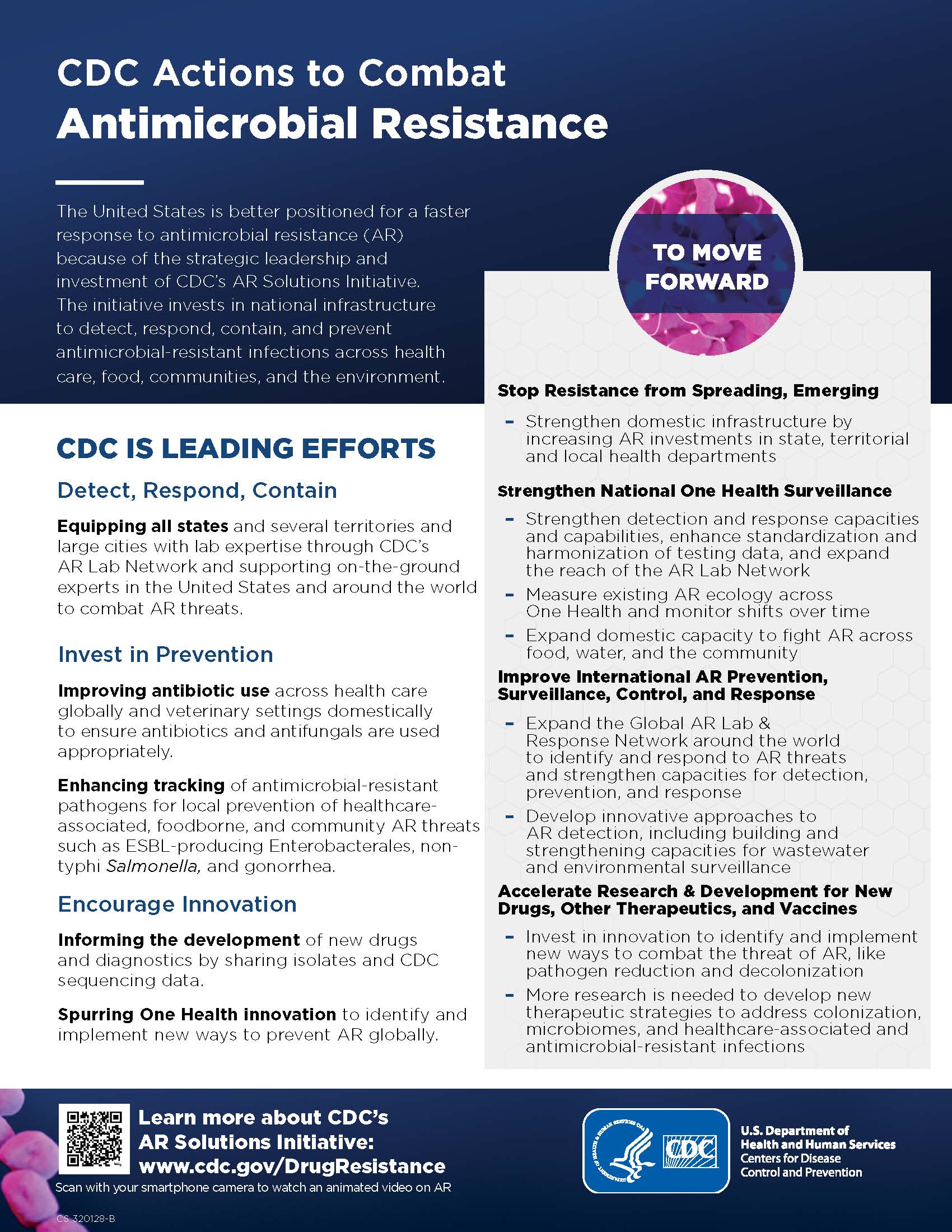

How is CDC responding to the threat of antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter?

CDC’s measures to curb the spread of antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter include:

- Tracking changes in antibiotic resistance among bacterial isolates from sick people through ongoing surveillance to help inform public health policy and action

- Supporting and strengthening local, state, and federal public health surveillance to enhance detection, reporting, and response to antibiotic-resistant infections

- Including strategies to support whole genome sequencing of Campylobacter isolates from people, meat sold at retail, and food animals

- Promoting initiatives that encourage appropriate antibiotic use in people and animals

- Determining foods responsible for outbreaks of Campylobacter infections

- Investigating and controlling Campylobacter outbreaks

- Guiding prevention efforts by estimating how much human illness occurs and identifying the sources of infection

- Educating people about how to avoid Campylobacter infections