Technical Report: Acute Hepatitis of Unknown Cause

This is a technical report intended for scientific audiences. For additional information, including materials targeted to the general public, is available here.

Executive Summary

This report reviews what is currently known about acute hepatitis with unknown cause in children under 10 years of age, and describes the investigations that CDC and state, local, tribal, and territorial partners are conducting in the United States.

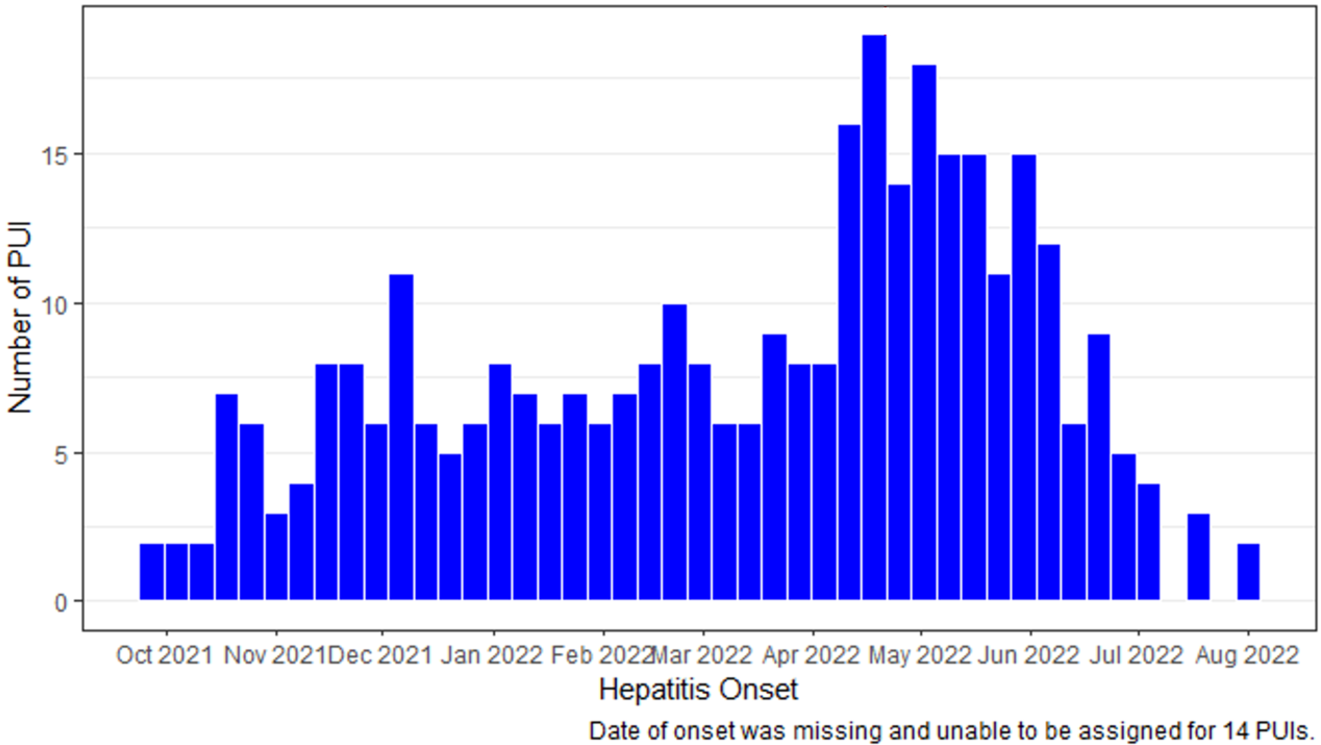

As of August 17, 2022, 358 patients under investigation (PUIs) have been reported in 43 states and territories, with dates of onset on or after October 1, 2021. The median age of PUIs is 2 years. To date, 22 (6%) PUIs have required a liver transplant, and 13 (4%) have died; cause of death is under investigation, awaiting additional medical records from jurisdictions. Analyses of syndromic surveillance data did not indicate recent increases in pediatric hepatitis-associated ED visits or hospitalizations, liver transplants, or adenovirus type 40 or 41 percent positivity among US children, compared with pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels.

Current patients under investigation (PUI) definition:

Children <10 years of age with elevated (>500 U/L) aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) since October 1, 2021 who have an unknown etiology for their hepatitis (with or without any adenovirus testing results, irrespective of the results)

CDC is investigating several etiological hypotheses, notably a possible association with any adenovirus infection, and specifically type 41 infection. Of the 299 PUIs for whom adenovirus testing was conducted on any specimen type (blood, respiratory specimens, stool), 45% were found to be positive for adenovirus. Additional hypotheses, including a possible association with current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, or other viruses, are also being evaluated. Details on the leading hypotheses, planned investigations, and what is known to date are available below.

Clinical providers caring for children with hepatitis of unknown etiology should refer to the latest guidance available. Guidance on adenovirus testing, typing, and testing submission is also available.

Disease Background

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver. Its causes include viral infections, alcohol use, toxins, medications, and certain medical conditions. In the United States, the most common causes of viral hepatitis are hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C viruses.[2] Signs and symptoms of hepatitis include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, light-colored stools, joint pain, and jaundice.[2] Treatment of hepatitis depends on the underlying etiology.

Adenoviruses are doubled-stranded DNA viruses that spread by close personal contact, respiratory droplets, and fomites.[3] There are more than 50 types of immunologically distinct adenoviruses that can cause infections in humans. Adenoviruses most commonly cause respiratory illness, but some adenovirus types can cause other illnesses such as gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis, cystitis, and, less commonly, neurological disease.[3] There is no specific treatment for adenovirus infections.

Adenovirus type 41 commonly causes acute gastroenteritis in children, which typically presents as diarrhea, vomiting, and fever; it is often accompanied by respiratory symptoms.[4] While there have been case reports of hepatitis in immunocompromised children associated with adenovirus type 41 infection, adenovirus type 41 is not known to be a cause of hepatitis in otherwise healthy children.[5, 6]

Epidemiological Data by Geographic Area

Globally, the World Health Organization is reporting 1,010 probable cases from 35 countries in five WHO regions, as of July 8, 2022. The majority of reported cases are from the WHO European Region (n=484), followed by the Region of the Americas (n=435), Western Pacific Region (n=70), the South-East Asia Region (n=19), and Eastern Mediterranean Region (n=2).

As of June 9, 2022, The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has received reports of 402 cases in 20 countries. Of the 192 cases for which this information was available, 17 (8.9%) have received a liver transplant. Overall, 293 cases were tested for adenovirus by any specimen type and had a valid positive or negative result. Of these, 158 (53.9%) tested positive. Of the 273 cases PCR tested for SARS-CoV-2, 29 (10.6%) tested positive. Additional information can be found on the ECDC website.

As of June 13, 2022, the United Kingdom is reporting 260 cases with onset dates between January 1, 2022 to present. Among 241 cases tested for adenovirus, 156 (65%) are positive. Of 196 patients tested for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, 34 (17%) have tested positive. Additional data from the UK are available on the UKHSA website.

Summary Data of Patients Under Investigation in the United States

As of August 17, 2022, 358 patients under investigation (PUIs) have been reported from 43 jurisdictions. The states reporting PUIs include AL, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, MD, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, ME, MI, MN, MO, MS, NC, ND, NE, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, PR, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WA, and WI.

The median age of PUIs is 2 years (0–9 years), and 48% of PUIs are male.

Of PUIs, 22 (6%) have required a liver transplant. Thirteen deaths among PUIs are under investigation. Among 13 PUIs who died, the median age was 1 year (range: <1 month–6 years) and four received a liver transplant. Six (46%) received a positive adenovirus test result (from any specimen type). Underlying health conditions were reported in 5 (38%) patients, including two who were immunocompromised. Investigations are ongoing and not complete for all PUIs.

Figure. Reported patients under investigation (PUIs) with hepatitis of unknown etiology by week of onset October 2021–August 17, 2022 (n=358)

Of the 299 (84%) PUIs with adenovirus testing on at least one specimen type (whole blood, plasma, serum, respiratory, stool), 45% were found to have adenovirus. Typing data are available for 22 PUIs; specific typing assays differed based on where the testing was performed. Typing through sequencing of hexon gene confirmed 13 PUIs were type 41, 1 was type 40, and 6 with other adenovirus types [type 1(n=3), type 2(n=1), type 5 (n=1), type 6 (n=1)]. Two of the 22 PUI specimens were positive for type 40/41 by group F specific qPCR.

Trends in Surveillance Data

Analyses of four data sources did not indicate recent increases in hepatitis-associated emergency department visits or hospitalizations, liver transplants, or adenovirus type 40 or 41 percent positivity among US children compared with pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels. Methods to establish baseline disease trends are presented in an MMWR publication. Subsequent analysis through early July have revealed the same trends.

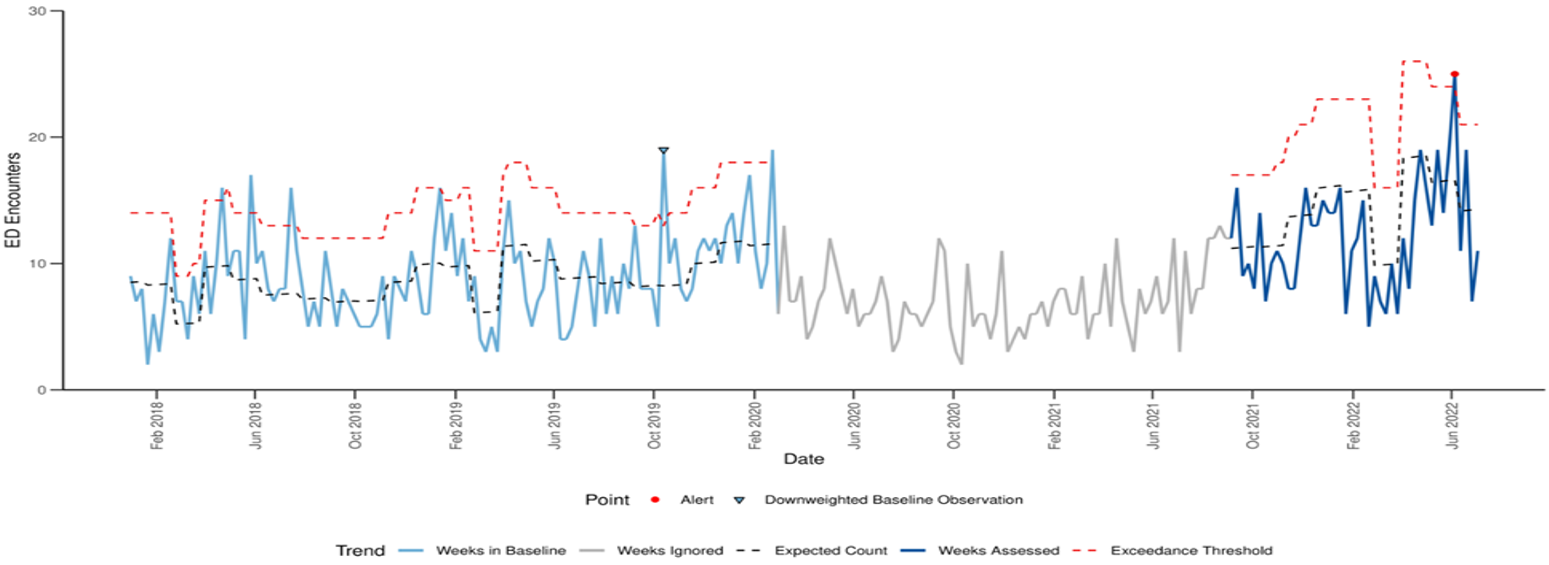

- Trends in ED visits by children for acute hepatitis are largely stable for children birth through 4 years and 5 through 11 years of age based on National Syndromic Surveillance Program data from January 2018 to July 2022.

- Liver transplants in the US among children aged <18 years do not demonstrate an increase since October 2021, compared with pre-pandemic levels in the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network.

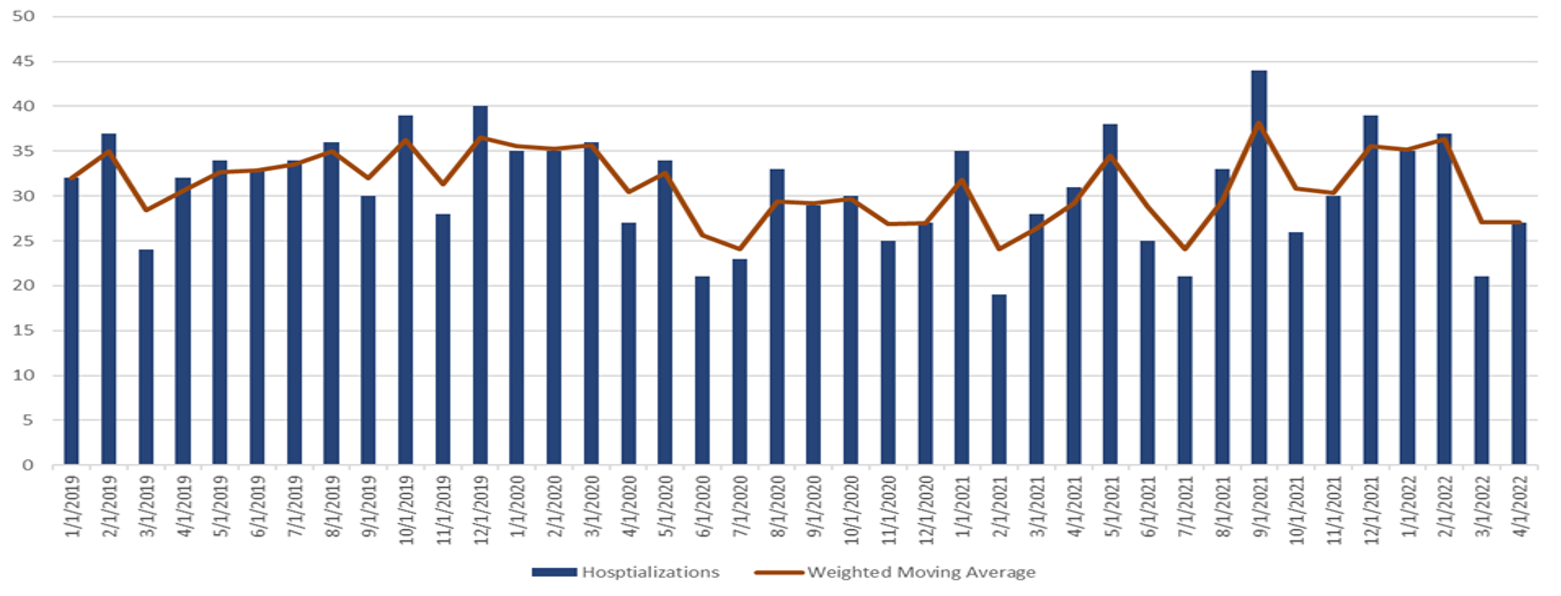

- Hospitalizations consistent with acute hepatitis among children from birth–4 years and 5–11 years do not demonstrate an increase from October to April 2021 compared with expected levels based on diagnostic codes in Premier Healthcare Database.

- Data from a large national commercial laboratory, by age birth–4 years and 5–9 years, do not show an in increase in the percent positive for adenovirus 40/41 from October 2021 to July 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic period (2017-2020).

Hypotheses under Investigation

CDC is investigating several etiologic hypotheses, notably a possible association with adenovirus infection, and specifically type-41 infection. Among PUIs for whom clinical testing for adenovirus was completed on any specimen type (blood, respiratory, stool), 45% are positive for adenovirus. Ongoing and planned investigations include adenovirus testing, including typing and genome sequencing, for all PUIs with residual specimens available. This will facilitate understanding of the range of adenoviruses associated with acute hepatitis and if adenovirus is a previously unrecognized cause of pediatric hepatitis in non-immunocompromised children.

Selected additional etiologic possibilities include:

- Do some children, due to age or other factors, exhibit an atypical response to their first adenovirus (or other viral) infection, which results in hepatitis? Pandemic mitigation measures have likely resulted in a large cohort of young children with minimal exposure to viral illnesses usually experienced in the first several years of life. Return to regular activities may have resulted in a larger than usual number of first infections, and at an older age than usual.

- Are multiple factors contributing to the illnesses seen among reported PUIs, as opposed to one primary driver? 30–50% [7–9] of liver failure in children is idiopathic; there are multiple known and unknown pathways to acute liver failure in children.

- Is acute hepatitis in children due to a combination of persistent or prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 (or other viruses) and adenovirus, causing an autoimmune phenomenon or superantigen reaction? Prevalence of an active SARS-CoV-2 infection is ~10% among PUIs for whom data is available, and up to 1/3 report history of prior COVID-19 infection. CDC updated its clinical guidance, recommending testing for past SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with acute hepatitis for epidemiologic purposes. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to confirm prior infections, as well as testing for viruses is ongoing.

- Is pediatric acute hepatitis caused by an environmental trigger or ingested toxin? Although epidemiological investigations are still underway for the majority of PUIs, no associations have been found with pets, food, medication, toxins, or other exposures evaluated.

Figure. Emergency department (ED) visits with hepatitis-associated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes* by week of visit among children aged 0-11 years — National Syndromic Surveillance Program, United States, January 2018–July 09 2022. Modified Farrington Algorithm with Pandemic Period‡ Ignored.

‡ Ignored pandemic period: Week of March 1, 2022 through week of August 29, 2021.

This method compares weekly emergency department visit counts to a weighted pre-pandemic baseline visit count. The blue dotted line models the weekly expected count of emergency department visits with pediatric hepatitis of unknown etiology*, based on weighted weekly counts during the baseline period of January 2018-February 2020. Large visit counts during the baseline period are down-weighted to prevent a loss of sensitivity during the weeks assessed (in dark blue). Down-weighted baseline observations are indicated by a downward facing light blue triangle. A weekly visit count above the exceedance threshold, shown by the red dotted line, represents a statistical increase in visits compared to this baseline. Statistical increases are detected for observations for which an exceedance score exceeds 1 and p < 0.05. During September 5, 2021–July 23, 2022, only the visit counts in the week ending on June 11, 2022 exceeded this statistical threshold. All other weeks since Sept 2021 have emergency department visit counts that were not statistically higher than expected.

Figure. Hospitalizations with hepatitis-associated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes* among children aged 0–11 years, by month of discharges, Premier Healthcare Database Special Release — United States, January 2019–April 2022

* ICD-10-CM Codes queried for hepatitis were as follows: B17.8 (other specified acute viral hepatitis); B17.9 (acute viral hepatitis, unspecified); B19.0 (unspecified viral hepatitis with hepatic coma); B19.9 (unspecified viral hepatitis without hepatic coma); K71.6 (toxic liver disease with hepatitis, not elsewhere classified); K72.0 (acute and subacute hepatic failure); K75.2 (nonspecific reactive hepatitis); and K75.9 (inflammatory liver disease, unspecified).

Investigations

Identifying the cause of acute hepatitis among children remains a high priority. CDC and partners are conducting extensive laboratory testing, including for adenovirus infection, and planning epidemiological and laboratory studies to examine the etiological hypotheses under investigation.

The following investigations are planned, ongoing or completed:

| Category | Investigation | Partners | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Medical chart reviews and exposure histories of PUIs to identify most commonly shared possible etiologies and eliminate less likely causes | State, Local and Territorial (STLT) public health authorities | Ongoing. Based on preliminary analysis, adenovirus was detected in approximately 50% of PUIs tested, and SARS-CoV-2 infection was detected in less than 10% of PUIs with a PCR or antigen test. |

| Prospective case-control study of ED/hospitalized patients to assess risk factors for acute hepatitis | CDC and STLT public health authorities | Ongoing. Protocol finalized and shared with jurisdictions. To date, 18 jurisdictions (16 states and 2 large cities have expressed interest) with MN, NE, FL obtaining a non-research determination with approval to enroll participants. | |

| Clinical | Clinical case series to describe the characteristics of a group of acute hepatitis patients, all of whom had adenovirus | CDC, STLT public health authorities | Completed. In-depth clinical case series review of the initial Alabama cases completed (data publicly available in MMWR link) and a case series of U.S, PUIs was published in the MMWR [link] Additional details can be found in NEJM [link] |

| Surveillance | Detection of human adenovirus (HAdV) 41 from stool testing to assess trends in number of tests and percent positivity | CDC, Labcorp | Ongoing. Data do not show an increase above pre-pandemic levels in the percent positive for adenovirus 40/41 from October 2021 through March 2022 compared to similar months in 2017–2019 MMWR [link] |

| Review MIS-C case surveillance data for trends in acute hepatitis over the past 2 years | CDC | Completed. Analysis of MIS-C surveillance data to examine patterns of hepatic involvement following SARS-CoV-2 infection over time indicated no increase in hepatic involvement after October 2021. | |

| Microbiology | Adenovirus typing of clinical specimens for PUIs | CDC (in collaboration with partners) | Ongoing. As of July 13, 2022, 280 PUIs have had adenovirus testing completed on at least one specimen type. Of 22 PUIs with typing data, 16 are type 40 or 41. |

| Detection of prior SARS-CoV-2 infections | STLT public health authorities and CDC | Ongoing. Recommendation made for testing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies as part of the evaluation of PUIs. Retrospective serologic testing of available specimens ongoing and investigation of prior test-confirmed infections. | |

| Metagenomics and whole genome sequencing of HAdV41 to understand pathogen variants and virulence factors, and detection of potential coinfections | CDC (in collaboration with partners) | Ongoing. Phylogenetic analysis of detected adenovirus strains. Testing of initial acute hepatitis cluster completed and will proceed for additional PUIs. Initial testing confirms presence of Adenovirus, type 41, as well as presence of Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) type 2. | |

| Detection of Adenovirus in fecal specimens from children with acute gastroenteritis to serve as control patients without hepatitis. | CDC and New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN) | Planned. Retrospective testing of specimens for AdV type 41 from a sentinel hospital active surveillance network for acute gastroenteritis in children across seven sites. Testing anticipated to begin in August 2022. | |

| Pathology | Pathology assessment of biopsy and explant liver tissue, and autopsy to investigate mechanism of liver injury | CDC and clinical institutions (as part of routine care) | Ongoing. As of July 22, 2022, CDC’s Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch has received formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver tissue specimens from 28 PUIs. Of 13 PUIs that have completed evaluation, 5 have had evidence of adenovirus species F by PCR. Similar to previous reports, liver tissue in these cases demonstrated varying degrees of active hepatitis, changes are non-specific but not typical for adenovirus hepatitis, with no viral inclusions observed and negative immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR has been negative on the 12 PUIs for which testing has been completed. |

Partnerships

CDC has hosted bi-weekly calls with state, tribal, local, and territorial partners to coordinate the investigations and response. In addition, CDC is working with groups representing clinical specialists from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN); Infectious Disease Society of America; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society; and American Academy of Pediatrics to produce diagnosis and management guidance for clinicians caring for patients with acute hepatitis of unknown cause. More information can be found on the NASPGHAN website. Clinical guidance for testing is posted on the CDC clinician portal: Clinical Guidance for Adenovirus Testing and Typing of Patients Under Investigation | CDC.

CDC is partnering with colleagues at state, local, tribal and territorial health departments, federal agencies, as well as clinical and laboratory experts at academic medical centers to conduct investigations to evaluate the leading etiological hypotheses. Further, the CDC is in close communication with colleagues in the United Kingdom, Israel, and regional/international health organizations; e.g., ECDC, PAHO, and WHO; to exchange data and findings.

Risk Assessment (at time of publication, August 17, 2022)

At this time, the incidence of acute hepatitis in children is not higher than pre-pandemic baseline levels, and severe outcomes are infrequent. Investigations are ongoing to better understand cases of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in children. CDC encourages parents and caregivers to be aware of the symptoms of hepatitis — particularly jaundice, which is a yellowing of the skin or eyes — and to contact their child’s healthcare provider if present.

Limitations of the Report

Adenoviruses are very common in humans and typically cause only mild illness. Few surveillance systems exist in the United States to detect adenovirus infections or distinguish it from the other pathogens that cause mild upper respiratory or gastrointestinal disease. CDC has leveraged existing data sources to define the burden of hepatitis and evaluate secular trends. Hepatitis emergency department and hospitalization data are based on discharge diagnosis codes that have not been extensively validated.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites.

References

- Baker JM. Acute Hepatitis and Adenovirus Infection Among Children—Alabama, October 2021–February 2022. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71.

- Hepatitis Webpage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/abc/index.htm

- Adenoviruses Webpage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: www.cdc.gov/adenovirus/index.html

- Kang G. Viral Diarrhea. International Encyclopedia of Public Health [Internet]. Elsevier; 2017. P. 260-7. Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780128037089/international-encyclopedia-of-public-health

- Munoz FM, Piedra PA, Demmler GJ. Disseminated Adenovirus Disease in Immunocompromised and Immunocompetent Children. CLIN INFECT DIS. 1998. Nov;27(5):1194-200. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/27/5/1194/480401

- Peled N, Nakar C, Huberman H, Scherf E, Samra Z, Finkelstein Y, et al. Adenovirus Infection in Hospitalized Immunocompetent Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004 Apr;43(3):223–9.

- Squires RH Jr, Shneider BL, Bucuvalas J, et al. Acute liver failure in children: the first 348 patients in the pediatric acute liver failure study group. J Pediatr 2006;148:652–8

- Alonso EM, Horslen SP, Behrens EM, et al. Pediatric acute liver failure of undetermined cause: a research workshop. Hepatology 2017;65:1026–37

- Squires JE, Alonso EM, Ibrahim SH, Kasper V, Kehar M, Martinez M, Squires RH. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Position Paper on the Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Acute Liver Failure. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2022 Jan 9;74(1):138-58.