Technical Report 4: Multi-National Mpox Outbreak, United States, 2022

Mpox Archive Content

You are viewing an archived web page, collected from CDC’s Mpox website. The information on this web page may be out of date.

Report reflects data and terms used as of October 21, 2022, prior to the World Health Organization’s decision to adopt the term “mpox.”

This technical report is for scientific audiences. Additional information, including materials for the general public, are available on the mpox site.

The report below provides timely updates regarding CDC’s ongoing response to the mpox outbreak in the United States and shares preliminary results of analyses that can improve understanding of the outbreak and inform further scientific inquiry. Each report features a combination of standing topics and the results of special analyses.

A supplementary analysis of national reproduction number estimates and newly created sub-national estimates is available.

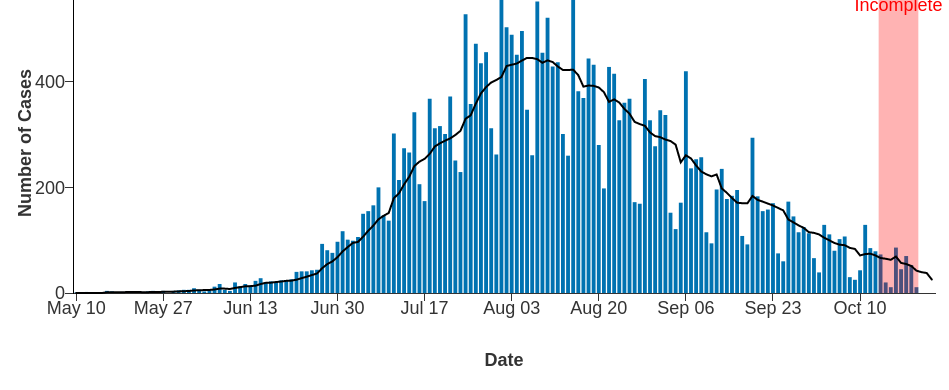

U.S. Case Data

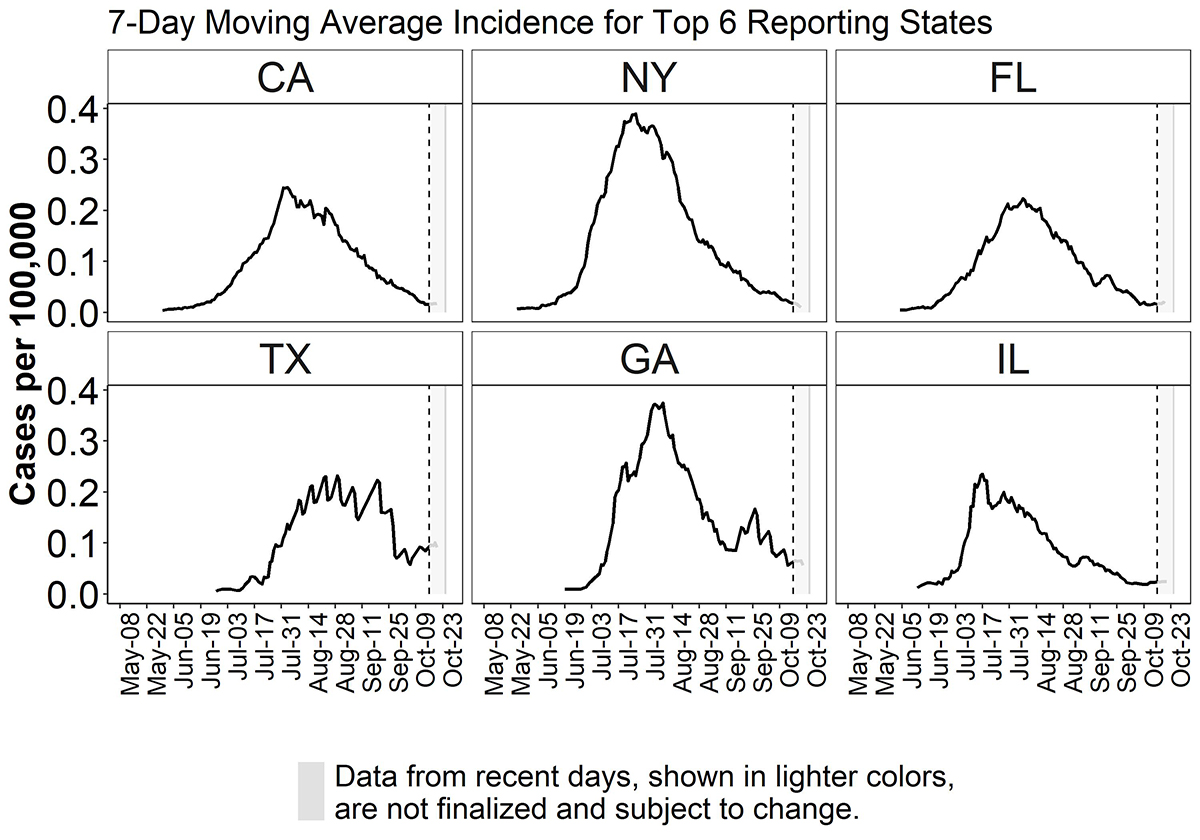

On May 17, 2022, the United States reported the first monkeypox case in the current outbreak. As of October 21, 2022, there are 27,881 cases across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (Figure 1). Case counts include those who tested positive for either monkeypox virus or orthopoxvirus as described in the 2022 Monkeypox Response case definition. The epidemiological curve of reported monkeypox cases to CDC through October 21, 2022, with a 7-day moving daily average (which adjusts visually for fluctuations in daily disease reporting), shows that reported cases peaked nationally in early August 2022 (Figure 2). The cumulative cases by jurisdiction aligned in time by the number of days that have passed since that jurisdiction first had one cumulative case per million population (Figure 3) and the daily case counts per 100,000 population for the top six jurisdictions reporting the highest percentage of cases (Figure 4). Case data are voluntarily reported to CDC by jurisdictions.

United States reported monkeypox cases per 100,000 persons in the population at increased risk of monkeypox virus exposure*

Data as of October 21, 2022

*The estimated population at increased risk is based on data from the National HIV Surveillance System for MSM with HIV and the National PrEP Surveillance Project for MSM on PrEP.

MSM = Men who have sex with men

Figure 1. Monkeypox Case incidence per 100,000 estimated MSM PrEP Indicated + MSM living with HIV by state or jurisdiction as of October 21, 2022.

Data from recent days, shown shaded, are incomplete

—7 Day Moving Average

Figure 2. Epidemiological curve of monkeypox cases by date (defined as the earliest among the date of illness onset, positive laboratory test report date, CDC call center reporting date, or case data entry date into CDC’s emergency response common operating platform, DCIPHER) as of October 21, 2022. Data for some cases may be updated when additional information is provided to CDC via DCIPHER.

Figure 3. Cumulative monkeypox cases per million by jurisdiction as of October 21, 2022. To allow comparison of curves, the curve for each jurisdiction starts on the day when that jurisdiction had experienced one case per million persons, cumulatively since the start of the outbreak. Case data are from DCIPHER and population data from the Census.

Figure 4. Epidemiological curve of 7-day moving average of monkeypox cases per 100,000 population by date (defined as the earliest among the date of illness onset, positive laboratory test report date, CDC call center reporting date, or case data entry date into CDC’s emergency response common operating platform, DCIPHER) from top six jurisdictions reporting cases as of October 21, 2022 (California (CA), New York (NY), Florida (FL), Texas (TX), Georgia (GA), Illinois (IL)). Data for some cases may be updated when additional information is provided to CDC via DCIPHER.

For the monkeypox cases reported, age information is available for 98.4% (n=27,421) of monkeypox cases reported to CDC’s Data Collection and Integration for Public Health Event Response (DCIPHER). The median age of cases is 34 years (range: <1 year to 89 years). Six deaths reported were attributed to monkeypox (as either a contributing cause or underlying cause), and several others are being investigated. As of October 21, CDC is aware of 38 total confirmed pediatric cases, defined as those under 18 years of age who presented with clinically compatible disease and tested positive with a monkeypox virus-specific test. Currently, all pediatric cases are subject to an in-depth interview and confirmatory molecular testing for monkeypox virus to eliminate the possibility of false positive test results that can occur in populations with low pretest probability of infection (Minhaj et al. 2022). As of October 21, investigations were launched for 127 pediatric monkeypox cases. There were 69 suspected cases aged 13–17 years, 21 of whom were confirmed cases, 43 of whom are under investigation or pending additional test results, and 5 were ruled out following confirmatory testing. Of 58 suspected cases aged 12 years or younger, 17 were confirmed cases, 19 under investigation or pending additional test results, and 22 were ruled out.

As of October 21, there are 17 confirmed or probable monkeypox cases among pregnant and recently pregnant people. Infections have occurred during all trimesters of pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes are being monitored. Two confirmed or probable monkeypox cases have been reported in people who are breastfeeding.

Data on sex assigned at birth are available for 75.9% (n=21,170) of cases reported to CDC. Among those with available data, 20,554 (97.1%) report male sex at birth, 616 (2.9%) report female sex at birth. Gender identity data are available for 83.3% (n= 23,229) of cases reported to CDC. Among those for whom gender identity is available, 22,203 (95.6%) are cisgender men, 639 (2.8%) are cisgender women, 45 (0.2%) are transgender men, 154 (0.7%) are transgender women, 187 (0.8%) are another gender identity, and one (0%) is multiple gender identities.

Gender or sex data are available for 98.4% (n=27,427) of cases reported to CDC. People whose reported sex differed from their reported gender were classified as transgender. Among people for whom reported gender was not available, but sex was reported, sex was used to categorize people as female or male. While the case report form specifies sex assigned at birth, there are variations in how jurisdictions collect sex, and in some cases, this may represent current gender. Recognizing these limitations, among those with available gender or sex data, 26,273 (95.8%) are categorized as cisgender men, 708 (2.6%) cisgender women, 67 (0.2%) transgender men, 191 (0.7%) transgender women, and 188 (0.7%) another sex or gender.

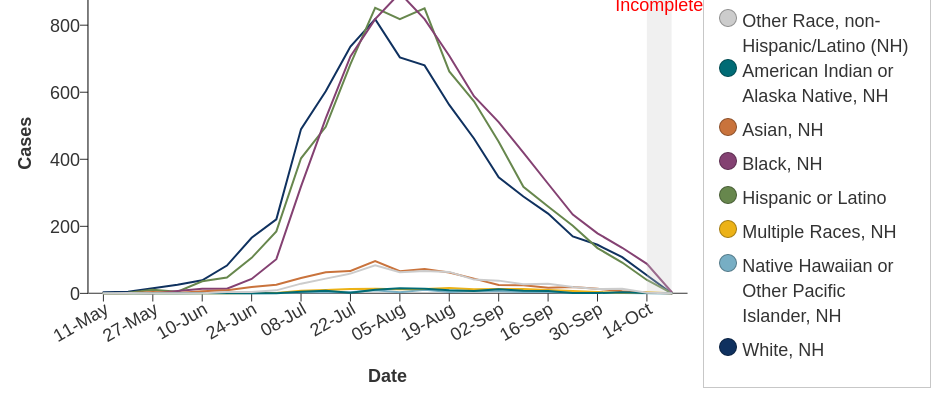

Race and ethnicity data are available for 83.6% (n=23,298) of cases reported to CDC. Epidemiological curves of all monkeypox cases reported to CDC by race and ethnicity provide data on changes by race and ethnicity group over time (Figure 5). The Hispanic or Latino category includes people of any race, and all other categories exclude those who identify as Hispanic or Latino. Approximately 32.0% (n=7,464) of cases with known race/ethnicity are Black, 31.1% (n=7,235) are Hispanic (of any race), 29.9% (n=6,971) are White, 3.0% (n=689) are Asian, and 2.6% (n=613) are reported as other race. Less than 1% (0.5%, 0.3%, 0.7%) of cases with available race/ethnicity data report being American Indian or Alaska Native (n=108), or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (n=65), or multiple races (n=153).

Figure 5. 7-day moving average of monkeypox cases by race/ethnicity and date (defined as the earliest among the date of illness onset, positive laboratory test report date, CDC call center reporting date, or case data entry date into CDC’s emergency response common operating platform, DCIPHER) and counts of monkeypox cases by race/ethnicity and week as of October 21, 2022. The Hispanic or Latino category includes people of any race, and all other categories exclude those who identify as Hispanic or Latino. Data for some cases may be updated when additional information is provided to CDC via DCIPHER.

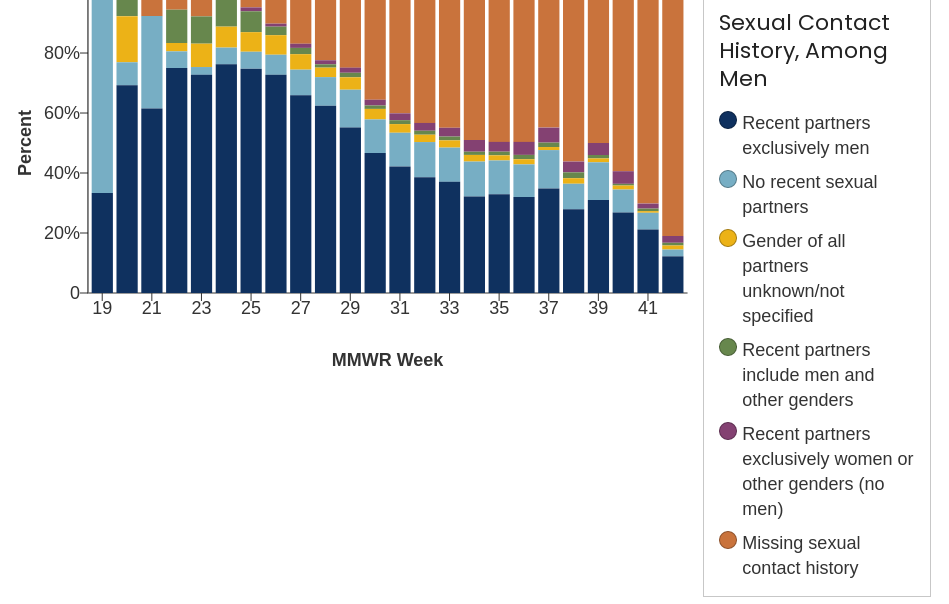

Recent sexual history is defined as any sex or close intimate contact in the three weeks preceding symptom onset. Due to the small number of cases in women and those with another gender identity, we did not further break these groups down by reported sexual contact history. Among the 27,427 people (98.4% of all cases) with sex/gender data, 26,340 cases (96.0%) were men (cisgender and transgender men included). For this group, reported history of recent sexual contact (including missing data) was characterized (Figure 6). Among the men (n=26,340), a total of 11,140 cases (42.3%) reported recent partners who were exclusively men (i.e., male-to-male sexual contact, MMSC), 10,534 cases (40.0%) had missing sexual contact history, 2,837 cases (10.8%) reported no recent sexual partners, 732 cases (2.8%) reported recent sexual contact with partners of unknown or unspecified gender, 709 cases (2.7%) reported recent partners who were exclusively women or other genders (no men), and 388 cases (1.5%) reported partners who were men and other genders (Figure 6). We note increasing proportions of cases missing data in this variable over time in conjunction with a declining proportion of cases reporting MMSC (discussed in more detail in the Dynamics of U.S. Outbreak in Technical Report 3). Some jurisdictions also report sexual orientation of cases to the CDC. Sexual orientation was reported in previous technical reports using data collected during early iterations of case reporting to CDC but is no longer nationally reported and is not included in this report.

Total cases reporting gender: 27,427; 98.37% of cases

Figure 6. Counts of all adults with known and unknown data on gender and proportion of men (cisgender and transgender men) by type of recent sexual contact (including missing or unknown information on recent partners) by the week (defined as the week of the earliest date among illness onset, reporting date defined as the positive laboratory test report date, CDC call center reporting date, or case data entry date into CDC’s emergency response common operating platform, DCIPHER) as of October 21, 2022.

Note: Gender or sex are available for 98.4% of adults, and sexual history among men is available for 60.0%. Data for some cases may be updated when additional information is provided to CDC via DCIPHER.

Signs and symptom data are available for 54% (n= 15,057) of cases reported to CDC. Among cases for whom signs and symptom data were available, nearly all reported rash (97.5%). Reported nonspecific prodromal signs included fever (65.8%), lymphadenopathy (swollen glands) (56.3%), rectal bleeding (22.3%), pus or blood in stool (18.4%), proctitis (swelling, soreness in the rectal area) (15.1%), and conjunctivitis (4.7%). Reported symptoms include: malaise (tiredness) (64.2%), chills (61.3%), pruritis (itching) (58.9%), headache (56.5%), myalgia (muscle aches) (54.9%), rectal pain (39.8%), tenesmus (cramping pain in the rectum) (20.3%), vomiting or nausea (18.1%), and abdominal pain (14.7%). Rash is part of the case definition and usually required for monkeypox testing.

As of October 20th, 2022, a total of 118,804 specimens have been tested for non-variola orthopoxvirus or monkeypox virus in the United States, including testing at public health and select commercial laboratories. Among those specimens, some of which may have come from the same patient, 27.9% were positive.

Starting shortly after the first monkeypox case was reported in the United States during the current outbreak, the two-dose JYNNEOS vaccine has been used to prevent the spread of the virus. The JYNNEOS vaccine is currently recommended for people who are at high risk for exposure and who might have been recently exposed. As of October 21, 2022, 989,533 doses have been administered and reported to CDC by 57 U.S. jurisdictions, including 50 states, New York City, Philadelphia, District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands. 653,229 (66.0%) of these doses were first doses, and 335,345 (33.9%) were second doses.1 Administration of first doses peaked during the week of August 7–13, 2022. (Figure 7)

Monkeypox Vaccine Administered, by Dose Number and Date of Administration

Data Reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022

Figure 7. Counts of monkeypox vaccine administered by date of administration, grouped into weeks. The bar is segmented, with the bottom segment representing first doses administered and the second segment representing second doses administered. Data for vaccines administered the week of October 16, 2022, are not shown due to potential delays in reporting. The latest data on monkeypox vaccine administration in the U.S. are available at Mpox Vaccine Administration in the U.S. Data are from the CDC Immunization Data Lake and represent data submitted as of October 21, 2022, 4:00 am EDT.

The recommended interval between the first and second JYNNEOS vaccine dose is 28 days. Among 551,505 people who were at least 28 days past their first dose and eligible to receive a second, 58.4% (n=321,843) received their second dose.2 These data about second dose receipt do not include vaccines administered and reported by Texas, which provides aggregated vaccine administration data to CDC.

Since September 2022, second doses have comprised a larger proportion of total vaccinations administered due in part to expanded vaccine availability. When initial vaccine supply was limited during the early months of the monkeypox outbreak, some jurisdictions with the highest incidence prioritized first dose administrations. On August 9, 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization that enabled health care providers to administer a smaller dose of the JYNNEOS vaccine (0.1 mL injection volume) intradermally for adults aged 18 and over, while also expanding subcutaneous administrations of the JYNNEOS vaccine (0.5 mL injection volume) to people under the age of 18 at high risk of monkeypox infection.

Before August 9, 2022, among 192,360 people who received at least one vaccine dose, 85.8% (n=165,130) received a subcutaneous injection, 2.6% (n=5,005) received an intramuscular injection, and 0.1% (n=112) received an intradermal injection. 11.5% (n=22,113) had an unknown or other route of administration. The percentage of first doses administered intradermally increased after August 9, 2022. During the week of October 9, 2022, among 10,713 people who received at least one dose, 77.4% (n=8,290) received an intradermal injection, 11.5% (n=1,232) received a subcutaneous injection, and 2.5% (n=264) received an intramuscular injection. 8.7% (n=927) had an unknown or other route of administration. These data about route of administration do not include vaccines administered and reported by Texas, which reports aggregated vaccine administration data to CDC. (Figure 8)

1 The remaining 959 doses were categorized as third, fourth, or fifth doses. These might reflect additional doses given after an administration error. Or, they might reflect instances where the same recipient identifier was assigned to multiple people in a jurisdiction, resulting in doses being erroneously considered to be third, fourth, or fifth doses.

2 Incorporates 7-day lag for reporting delay; among people who received their first dose prior to September 16, 2022.

Monkeypox Vaccine First Doses Administered, by Route of Administration

Data Reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022

Figure 8. Distribution of first dose monkeypox vaccine administrations by route of administration for each week of administration beginning May 22, 2022. Data for vaccines administered the week of October 16, 2022, are not shown due to potential delays in reporting. Four routes of administration are presented: intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, and unknown or other route. Data are from the CDC Immunization Data Lake and represent data submitted as of October 21, 2022, 4:00 am EDT.

Vaccination Administration Data by Demographics

Data on the sex of the vaccine recipient were available for 98.2% (n=641,731 out of 653,229) of first doses reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022. Among people who received at least one vaccine dose, 90.2% (n=588,958) were male and 8.1% (n=52,773) were female. Data on other gender identities are not collected for vaccine administrations.

Data on the age of the vaccine recipient were available for nearly all first doses reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022. Among people who received at least one vaccine dose, 7.8% (n= 50,933 out of 653,229) were aged 18–24, 46.9% (n= 306,610) were aged 25–39, 18.2% (n=118,595) were aged 40–49, 21.3% (n=139,267) were aged 50–64, and 5.6% (n=36,813) were aged 65 and over. 0.2% (n=1,003) were pediatric recipients under age 18.

Data on the race and ethnicity of the vaccine recipient were available for 91.0% (n=594,492 out of 653,229) of first doses reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022. Among people who have received at least one vaccine dose, 46.9% (n=306,209) were non-Hispanic White, 20.4% (n=133,362) were Hispanic or Latino, 11.4% (n=74,193) were non-Hispanic Black, 6.9% (n=44,898) were non-Hispanic Asian, 4.9% (n=31,991) were non-Hispanic multiple race or other race, 0.4% (n=2,299) were non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native, and 0.2% (n=1,540) were non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. The distribution of first doses administered by race/ethnicity has changed by week of administration (Figure 9).

Monkeypox Vaccine First Doses Administered, by Race/Ethnicity

Data Reported to CDC as of October 21, 2022

Figure 9. Distribution of first dose monkeypox vaccine administrations by race/ethnicity overall and for each week of administration beginning May 22, 2022. Data for vaccines administered the week of October 16, 2022, are not shown due to potential delays in reporting. Nine race/ethnicity groups are presented: NH (non-Hispanic) White, Hispanic or Latino, NH Black, NH Asian, NH other race, NH multiple race, NH American Indian/Alaska Native, NH Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and unknown. Weeks where there were fewer than 30 vaccination administrations are not shown. Data are from the CDC Immunization Data Lake and represent data submitted as of October 21, 2022, 4:00am EDT.

Dynamics of U.S. Outbreak

Current Transmission Level

CDC is closely monitoring the nature of monkeypox transmission dynamics in the United States. Following levels defined by the UK Health Security Agency, the outbreak is likely to follow one of these four transmission scenarios:

- Imported cases with limited onward transmission

- Spread within a defined subpopulation

- Spread within multiple subpopulations or larger subpopulation

- Significant, community-wide transmission

The United States is mostly experiencing spread within a defined subpopulation, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). We have high confidence3 in this assessment.

We base this assessment on epidemiological data indicating that there is a large degree of missingness for sexual history but the vast majority of cases have thus far occurred in adult men and among those reporting sexual contact with other men (for whom sexual activity is reported), both in the United States and globally. We have also observed few cases of transmission to household contacts and nonsexual contacts to date. Finally, extrapolating from modeling work performed in the United Kingdom (UK) (Brand et al. 2022; Endo et al. 2022), the potential for sustained spread among heterosexual networks is likely low, based on relatively lower sexual partnership formation rates overall. However, we note there are subpopulations within heterosexual networks that have high sexual partnership formation rates.

3 In this report, we use the following definitions for confidence levels associated with analytic judgments: High-confidence judgments are based on high-quality information from multiple sources, although such judgments are not a certainty and still carry a risk of being wrong. Moderate-confidence judgments are based on credibly sourced and plausible information, but the information is not of sufficient quality or corroboration to warrant a high level of confidence. Low-confidence judgments are based on information that is fragmented or poorly corroborated or upon data sources for which there are significant concerns or problems.

Outbreak Reproduction Number Estimates

Based on analysis through October 24, 2022, the growth rate of the monkeypox outbreak in the United States is slowing. We have high confidence in this assessment.

We estimate the time-varying reproduction number (Rt), which is the average number of secondary cases infected by a single primary case in a large population, has been below one since late July (Figure 10). Analyses were conducted using the EpiNow2 package, which adjusts for truncated data and reporting delays, using three parameter distributions: generation interval, incubation period, and delay from symptom onset to report date.4

4 The generation interval and incubation period are internal estimates updated from Charniga K, Masters NB, Slayton RB, Gosdin L, Minhaj FS, Philpott D, et al. Estimating the incubation period of monkeypox virus during the 2022 multi-national outbreak. medRxiv. 2022

Figure 10. Top panel shows estimates of cases by date of report with actual cases shown by gray bars. The bottom panel shows estimates of the effective reproduction number by date. In both panels, shaded regions reflect 90%, 50%, and 20% credible intervals in order from lightest to darkest. Green shows estimates, red shows estimates based on partial data, and purple shows forecasts. Report date is determined by a hierarchy across the different data streams where priority is given to diagnosis date, orthopoxvirus test date, orthopoxvirus test confirmation date, case investigation start date, orthopoxvirus sample collection date, date of call to CDC call center, report date (to public health department, county, or state), date CDC announced case, and the date the case was entered into DCIPHER, in that order. Note that this date is distinct from the dates used elsewhere in this report. We have updated the approach for modeling the reporting process from Technical Report 3 to better estimate delays in case reporting.

The slowing growth of the outbreak is likely due to a combination of many factors, including vaccination, behavior change, and possibly increases in infection-acquired immunity among a segment of affected sexual networks. As we noted in Technical Report 3, the timing of this slowing suggests it is unlikely to be due to vaccination alone. The 50% credible interval of our estimates of the effective reproduction number for the time period, based on partial data and the forecasted time period, remain below 1.0. However, the 90% credible interval that includes 1.0 may indicate:

- A slowing in the rate of decline nationally

- Changes in regional or state-level trends

- Changes in state-level reporting patterns that are not fully accounted for by the model of the reporting process

An online survey of gay, bisexual, and other MSM conducted in early August found half of respondents reported that they had changed their behavior and reduced sexual partners and encounters due to the monkeypox outbreak (Impact of Monkeypox Outbreak on Select Behaviors | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC). Therefore, continued effective health communication and protective behavior messaging, coupled with strong and equitable vaccination uptake, are necessary to sustain declines in cases. If these efforts are not sustained, there is a possibility that the declining trends could be reversed, and the incidence of new cases could increase again.

Vaccination remains an important tool as the outbreak evolves and vaccination coverage, especially of second doses, increases. As of October 21, 2022, 989,533 doses of JYNNEOS vaccines have been administered (Monkeypox Vaccine Administration in the U.S. | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC). An analysis comparing monkeypox incidence in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals is underway using surveillance data for individuals in the group recommended to be vaccinated. Preliminary results posted on September 28, 2022 estimate a 14-fold higher monkeypox incidence in unvaccinated individuals compared to those who were vaccinated at least two weeks earlier (Rates of Monkeypox Cases by Vaccination Status | Monkeypox | Poxvirus | CDC ). Studies to further evaluate vaccine effectiveness are underway.

Serial interval and updated incubation period estimates

We estimated key epidemiological parameters: the serial interval and incubation period for both symptom onset and rash onset for monkeypox virus infection. Further details can be found in this preprint: Serial interval and incubation period estimates of monkeypox virus infection in 12 U.S. jurisdictions, May – August 2022 | medRxiv. The overall mean estimated serial interval for earliest symptom onset was 8.5 (95% Credible Interval (CrI): 7.3–9.9) days (SD: 5.0 [95% CrI: 4.0–6.4] days) for 57 case pairs and rash onset was 7.0 (95% CrI: 5.8–8.4) days (SD: 4.2 [95% CrI: 3.2–5.6] days) for 40 case pairs when the gamma distribution was used to model both distributions (Figure 11). The mean estimated incubation period from exposure to earliest symptom onset was 5.6 (95% CrI: 4.3–7.8) days (SD: 4.4 [95% CrI: 2.8–8.7] days) for 36 cases, while the mean incubation period from exposure to rash onset was 7.5 (95% CrI: 6.0–9.8) days (SD: 4.9 [95% CrI: 3.2–8.8] days) for 35 cases (Figure 12). Note that rash was often not the earliest symptom and that not all cases were included in both analyses.

For serial interval estimation, data from primary and secondary case pairs were compiled by 12* state and local health departments. Cases were included only if they showed a high degree of certainty that the secondary case was infected by the primary case.

For each case pair, we calculated the number of days between onset of any monkeypox symptoms, as well as the number of days between rash onset, in the primary and secondary cases. We used the EpiEstim package in R software to estimate the distribution of the serial interval for known primary and secondary case pairs using Bayesian methods. We did not adjust for right-truncation of the data as cases from four months of the outbreak were included.

For incubation period estimation, we added 14 U.S. cases to the monkeypox virus incubation period analysis first reported in preprint on June 23, 2022. In contrast to this preliminary analysis, we only included U.S. cases, because we hypothesize that there may be differences across countries which could be related to the selection of cases and therefore, introduce selection bias. As in the Charniga et al. preprint, we assumed a log normal distribution for the incubation period.

The estimated serial interval for symptom onset (8.5 days) was longer than the incubation period (5.6 days), suggesting most transmission occurred after the onset of any symptoms in the primary case. Conversely, the point estimate of the serial interval for rash onset (7.0 days) was slightly shorter than the point estimate for the rash incubation period (7.5 days), which suggests pre-rash transmission can occur, but the credible intervals were large and overlapping. Our estimate of the serial interval includes more case pairs than have been reported previously, and we include estimates for rash onset, which may be more reliable than initial symptoms.

*California, Chicago, Colorado, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, New York City, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Hawaii contributed data, but the case pairs did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Figure 11. Empirical and fitted distributions of the serial intervals for rash (N=40) and earliest symptom (N=57) onset for monkeypox virus, United States, May–August 2022. Colors represent U.S. jurisdictions (N = 11). AIC values for each model are shown inside the plots in the upper right corner.

Figure 12. Updated estimated cumulative density functions according to a log-normal distribution of monkeypox virus incubation periods, United States, May–August 2022. (A) symptom onset (N = 36) and (B) rash onset (N = 35).

Potential Future Outbreak Trajectory

Short-Term Scenarios

Possible outbreak growth scenarios for the United States over the next two to four weeks are the following:

1) Daily cases will continue to decline or plateau

2) Very slow growth with daily cases rising slowly

3) Exponential growth with daily cases rising

Among these scenarios, we assess daily cases in the United States will most likely continue to decline or plateau over the next 2 to 4 weeks. Sporadic sub-national clusters may continue to occur in this scenario. We have moderate confidence in this assessment but note the possibility, as described above, that incidence could increase again.

Our rationale for this assessment is based on the estimates of Rt below 1. However, we note cases are not declining in all jurisdictions. Because the causes of cases slowing in the United States and other countries are not well understood and patterns have not been uniform, we cannot predict the timing and precise trajectory of case declines in the United States.

Longer-Term Considerations

There is a great deal of uncertainty over the longer-term trajectory for the monkeypox outbreak in the United States, owing to a range of unknowns including the following:

- Detailed characteristics of sexual networks involving gay, bisexual, and other MSM and the extent and duration of behavior change on outbreak trajectory among MSM

- Uptake and effectiveness of vaccines and other interventions on outbreak trajectory among MSM

- Pre-exposure and post-exposure vaccine effectiveness against infection and severe disease

- Potential for sustained transmission among non-MSM populations

- Extent and impact of asymptomatic spread of infection

- Potential impact of viral mutation on transmission dynamics

Our current assessment for the most likely longer-term scenario is that the outbreak will remain concentrated in MSM, with cases slowing over the coming weeks, and falling significantly over the next several months. We have moderate confidence in this assessment. We note that low-level transmission could continue indefinitely in defined subpopulations, and the cumulative number of cases that could occur among MSM is unknown.

We believe this scenario is most likely because the outbreak to date has remained concentrated among MSM. Monkeypox spread in other subpopulations has so far not been extensive, and there is no country in this outbreak with clear evidence of sustained transmission outside of MSM networks. A prior outbreak in Nigeria, an endemic country, was associated with contemporaneous circulation of multiple haplotypes, and provides a hypothesis to understand multiple transmission pathways in endemic countries during the current outbreak. While the declining proportion of cases reporting recent male-to-male sexual contact in the United States (Figure 6) and among MSM globally could signal potential for spread in other subpopulations, this finding is possibly an artifact due to missing data. We also make this assessment assuming monkeypox infection provides strong immunity to subsequent infection, as is the case for other orthopoxviruses, which will eventually lead to a depletion of susceptible individuals among populations disproportionately affected.

We note that mathematical models have shown considerable variability in predicted levels of cumulative incidence among MSM (Brand et al. 2022; Endo et al. 2022; van Dijck et al. 2022; personal communication and internal modeling results). The duration of the intense transmission phase for this outbreak is also highly uncertain. If spread is concentrated among a subset of MSM more likely to experience exposure, and vaccination is well focused in this exposure group and strongly protective against infection, a more rapid decline and lower cumulative number of cases could occur (Badham and Stocker 2010). However, if spread is less concentrated among a subset of MSM more likely to experience exposure, or if vaccination and behavior change only gradually slow spread, a cumulatively high number of MSM infections and a long outbreak tail are possible.

Given our uncertainty over how the monkeypox outbreak may unfold in the United States, we acknowledge several other less likely but possible scenarios that could transpire, some of which could require major shifts in our outbreak response posture.

Elimination: Domestic transmission in the United States is unlikely to be eliminated in the near future due to the possibility of continued travel related introductions and of domestic transmission. Elimination could occur if monkeypox remains concentrated in a subset of MSM more likely to experience exposure, long-term vaccination efforts are focused on this exposure group, and these efforts are effective in preventing infection.

To achieve and maintain elimination, extensive efforts would be required, including ongoing vaccination efforts as new individuals enter the high-risk population, and non-pharmaceutical interventions to control future travel-related introductions from countries with ongoing transmission. Concerted global action to control monkeypox will increase the likelihood of elimination in the United States as well as globally.

Acceleration: The monkeypox outbreak could accelerate in the United States over the next several months and affect an increasingly wider portion of the United States population. This scenario is most likely to occur if transmission occurs more readily than expected among non-MSM populations including potentially among highly connected heterosexual networks or by nonsexual routes, or if risk-reduction behaviors decline among the most at-risk communities before vaccination coverage reaches high enough levels to protect them. At present there is no compelling evidence in favor of this scenario though behavior may continue to change as the size of the perceived threat recedes.

Establishment in animal populations: There is a possibility that the monkeypox virus could establish itself in one or more animal populations in the United States, although this scenario would require that a suitable reservoir animal host exists, which is currently unknown. If such a reservoir host exists, this scenario could become more likely if case numbers rise. Several animal species in North America, both wild and domestic, may be susceptible to monkeypox infection and may be able to transmit the virus to other animals or species (Hutson et al. 2010, Parker et al. 2013, Reynolds et al. 2019, Seang et al. 2022).

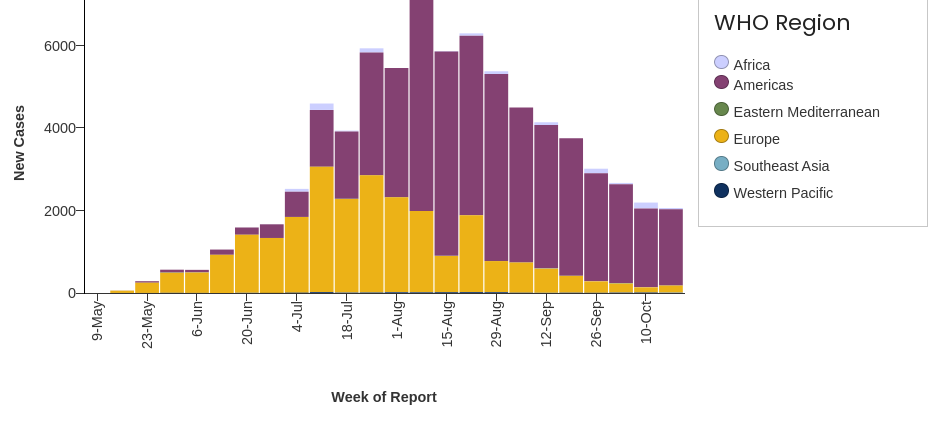

Global Outbreak

As of October 21, 2022, WHO has reported 75,348 cases and 33 deaths from monkeypox in 109 countries, territories, and areas associated with the 2022 multi-national outbreak. This count may include confirmed cases not yet reported in World Health Organization (WHO) official counts. Countries may also use their own case definitions separate from those outlined in this report.

The epidemic curve by WHO region (Figure 13) shows an evolving outbreak. The Americas continues as the region with the highest burden of new cases. In non-endemic countries, the outbreak continues to primarily affect men who have reported recent sex with one or more partners, notably other men. Figure 14 displays weekly new cases per 100,000 population over time among the 12 countries with the highest cumulative cases reported. The United States, Canada, and European countries are experiencing clear declines in incidence. In Latin America, Brazil and Peru are also experiencing a decline in incidence as compared to the summer. However, the weekly incidence per 100,000 persons in Colombia and Mexico appears to be increasing.

The 2022 Monkeypox and Orthopoxvirus Global Outbreak Map shows the geographical distribution of global monkeypox cases.

Figure 13. Weekly new monkeypox cases by WHO region globally as of October 21, 2022. CDC, WHO, European CDC, US CDC, and Ministries of Health.

Figure 14. New weekly case counts per million population for the top 12 countries by cumulative case count as of October 21, 2022. The graphs use three y-axis scales, one for each row of graphs. Note the most recent weeks’ data might represent case undercounts, as some data might not yet be reported. CDC, WHO, European CDC, US CDC, and Ministries of Health.

CDC’s Monkeypox Vaccine Equity Pilot Program can support public health jurisdictions’ efforts to reduce monkeypox vaccination disparities. Barriers to vaccination may include differences in language, location of vaccination sites, vaccine hesitancy, mistrust of government, and lack of access to online scheduling technology. As of October 21, CDC has approved eight proposals from jurisdictions to implement monkeypox vaccination projects in populations disproportionately affected by monkeypox who are also experiencing vaccination disparities. These include Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. One vaccination project in this category has been completed, reaching over 4,000 vaccine recipients. In addition, jurisdictions are currently implementing seven other projects in this category with a combined goal of vaccinating 2,700 people.

In addition, CDC is supporting public health jurisdictions’ vaccination initiatives at events focusing on the general LGBTQ+ population, such as Pride festivals. As of October 21, CDC has approved 14 monkeypox vaccination projects in this category. This includes six completed projects (which vaccinated a total of nearly 16,000 people) and eight projects that have not yet been completed (through which jurisdictions plan to vaccinate a combined total of 7,300 people).

Recent Pride events underscore the benefits of federal-state partnerships and the importance of including community-based organizations to reach affected populations. In events leading up to and during Southern Decadence and Atlanta Black Pride, health care workers administered a total of nearly 7,000 monkeypox vaccine doses and over 4,200 doses, respectively. These efforts suggest that community engagement, targeted messaging, and selecting venues that affected populations frequent should be considered to improve vaccine equity and reduce health disparities. CDC recently published an analysis of data from the Southern Decadence event and the Atlanta Black Pride weekend festival in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Limitations of the Report

All data are preliminary and may change as additional data are obtained.

Due to the limited availability of detailed data from case reports and contact tracing, we continue to have knowledge and data gaps related to monkeypox transmission dynamics, case ascertainment, clinical characteristics, and other features of this outbreak. CDC is working with state, local, tribal, and territorial partners, as well as clinical and laboratory partners, on obtaining improved case and contact tracing data to better understand this rapidly changing outbreak. CDC is also working with other federal partners and academic partners to improve our ability to respond to this outbreak.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by HHS or CDC.

References to non-CDC sites on the internet are provided as a service to readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites.

Acknowledgements

Authors of and contributors to this report are members of CDC’s 2022 Multi-National Monkeypox Outbreak Response. This report was co-led by the Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics and the Epidemiologic Task Force.

References to non-CDC sites are provided as a service and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed were current as of the date of publication.