Outbreaks and Emergency Response

Ebola Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

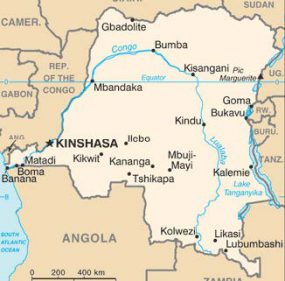

On July 30, 2018, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) confirmed an outbreak of Ebola in North Kivu, an area that has suffered years of insecurity. This is now the second-largest Ebola outbreak in history. CDC is working closely with other US government agencies and international partners to support DRC to control the outbreak. CDC has deployed experts to DRC, neighboring countries, and the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters. At CDC headquarters in Atlanta, a team is providing technical guidance and cross-agency coordination. The CDC DRC country office is supporting this response, and CGH’s long-term disease control and capacity-building investments in DRC have been valuable assets. CDC has helped DRC train 196 Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) graduates since 2013, many of whom are deployed to support Ebola case investigations, active case finding, and contact tracing in North Kivu. CDC is also helping DRC establish a Center for Excellence for Ebola. Initial implementation will focus on strengthening outbreak coordination and data management, using practical experience from the current Ebola response.

CDC offices in Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Kenya are actively supporting Ebola preparedness, leveraging CDC in-country investments to improve surveillance, laboratory capacity, and rapid response, in collaboration with ministries of health and international partners.

To prepare for and limit cross-border spread of Ebola, CDC staff, working with WHO colleagues, have helped ministries of health in Uganda, South Sudan, and Rwanda provide Ebola vaccine to health care staff and frontline workers. During 2018, 3,000 health care and frontline workers were vaccinated in Uganda; Ebola vaccination was introduced in South Sudan in January 2019 and in Rwanda in March 2019. CDC staff also worked with countries to update vaccination protocols, develop standard operating procedures and training materials for Ebola outbreak preparedness and response, and define high-risk target populations. CDC’s work across multiple countries has helped standardize processes and facilitate dissemination of best practices.

Ebola’s Deadly Lasting Effects

A mother and her three children in Liberia. Credit: Leslie R. McCree

More than four years after the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa that infected 28,000 people and claimed 11,000 lives, new information is being uncovered about the lasting effects of the virus on survivors. In 2018, CDC and partners published a study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases documenting how a small cluster of Ebola cases occurred in Liberia in November 2015 after the end of the Ebola epidemic, raising the possibility of transmission from a persistently infected person.

CDC and partners conducted an outbreak investigation that revealed evidence that a patient in the November 2015 cluster survived Ebola in 2014 and may have had viral persistence or recurrent disease and transmitted the virus to other family members a year later. Evidence from this investigation suggests that Ebola can persist after a patient recovers from acute infection. It highlights the risk that Ebola may reemerge, even after active transmission is interrupted. Transmission from latent infections is rare, but the findings show the importance of continued surveillance once countries are declared Ebola free. Resurgence can occur, and countries must remain vigilant and continue to focus efforts on strengthening health systems to prevent, detect, and respond to Ebola and other infectious diseases. These diseases can spread rapidly and have a devastating impact on countries, communities, families, and patients.

Fighting Zika at Home and Abroad

A blood-engorged female Aedes albopictus, a Zika-transmitting mosquito, feeding on a human host.

The 2015–2017 Zika outbreak posed a significant public health challenge globally. CDC worked closely with US government agencies and local and international partners to minimize the number of pregnancies affected by Zika virus infection and to build capacity to better understand the virus. Through partnerships, CDC rapidly implemented Zika activities across Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa, with a focus on six functional areas: emergency response; vector control and management; innovations; laboratory capacity; maternal and child health; and surveillance, epidemiology, and public health investigations.

By the fall of 2018, the majority of these activities had been completed, advancing a deeper understanding of Zika and its long-term consequences on affected countries and at-risk populations. CDC and partners established regional networks of entomological surveillance and expertise in Central America, the Caribbean, and West Africa, covering more than 45 countries; strengthened laboratory capacity in 123 countries; and conducted pregnancy cohort studies in Haiti, Colombia, Panama, El Salvador, Guatemala, Kenya, and Thailand.

Measles Outbreaks Around the World

Since 2000, measles deaths have been reduced by 80%, and measles elimination efforts have prevented an estimated 21.1 million deaths globally.

In Nigeria, a little girl prepares to receive her measles vaccination.

However, from 2017 to 2018, provisional data indicate the number of measles cases has risen by 50%, with many regions around the world experiencing large, often prolonged outbreaks of the disease. During this time, major outbreaks occurred in Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Israel, Madagascar, the Philippines, Venezuela, and Ukraine.

CDC staff in Atlanta and staff deployed to key countries are working with partners to address global measles outbreaks. CDC is supporting in-country immunization activities, specialized laboratory testing, and regional and national trainings on preparedness for importation of measles. Additionally, CDC is helping countries and partners identify and investigate suspected measles cases and assisting with ongoing vaccination strategies and outbreak response.

In 2018, CDC supported 15 countries with outbreak investigation and response and supported 4 countries with supplemental immunization activities to address endemic measles virus transmission. These activities led to more than 119 million people getting vaccinated globally in 2018.

Measles outbreaks illustrate how fragile gains in disease elimination are. To make further progress, case-based surveillance must be strengthened, vaccination uptake should increase, and political commitment and investment in immunization programs must be secured.

Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus (VDPV) Outbreaks

Outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) have occurred in geographic areas in several countries where populations are under-immunized or not immunized, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Somalia, and Syria. These outbreaks have occurred mostly in countries that are free from wild poliovirus but where polio vaccine coverage among children is low because of weakened health infrastructure. CDC and partners use the same proven strategies for stopping wild poliovirus to respond to VDPV cases—strengthening surveillance systems and increasing vaccination coverage. Because of these strategies and the rapid mobilization of resources on the ground, outbreaks can be controlled quickly. For example, in Syria, CDC and partners deployed a comprehensive outbreak response and successfully stopped a VDPV outbreak in months, despite protracted conflict and instability.

Significant global progress against polio in recent years demonstrates that the resources, political will, technical and scientific know-how, and infrastructure for eradication are in place to stop both wild and vaccine-derived polio outbreaks.

Monitoring and Responding to Global Health Threats

CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program trains health workers on how to investigate health threats wherever they occur.

CDC works 24/7 to collect information about events around the world that could be serious risks to public health. In 2018, scientific and technical experts in Atlanta closely monitored 30–40 threats per day worldwide and tracked 139 events of public health importance.

Through CDC’s Global Emergency and Alert Response Service (GEARS), CDC has more than 400 CDC experts ready to deploy in response to a public health emergency anywhere in the world. In 2018, GEARS mobilized staff over 50 times to more than 45 countries to support outbreak response, including for yellow fever and Ebola, and to provide public health expertise, logging more than 3,680 cumulative days of deployment.

CDC does not rely solely on sending people to respond to outbreaks; we also work to build capacity in other countries for timely response and long-term sustainability in countries. CDC trains “boots-on-the-ground” disease detectives through the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP). In 2018, CDC-trained disease detectives investigated more than 220 threats across the globe. To expand detection and response capabilities at the local level, the FETP-Frontline program trained more than 1,130 individuals to serve at the forefront of the fight against infectious diseases. These FETP-trained responders were among the first on the scene to identify and contain outbreaks of international concern, like anthrax and polio. FETP graduates are working in more than 70 countries to stop outbreaks at their source before they spread.