Progress in Addressing Leading Causes of Death and Disability

CDC draws on an extensive network of international partnership and its technical capacities in infectious diseases, program implementation, public health surveillance and laboratory, workforce development, and emergency response, to address infectious disease outbreaks (like Ebola or COVID-19) and naturally occurring crises (like earthquakes and hurricanes) that can disrupt public health systems. CGH’s global health portfolio also focuses on long-standing global health challenges such as HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, parasitic diseases, and vaccine-preventable diseases including measles and polio. CGH’s global programs also work with countries to prepare for and respond to disease outbreaks, saving lives in the countries where CDC works, and contributing to a safer global community.

Workforce Development: Since 1980, there have been over 19,148 graduates of CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program, and CDC has supported more than 80 countries across Frontline, Intermediate, and Advanced program tiers.

Response to Outbreaks: Since 2005, there have been over 6,050 emergency outbreaks investigated by CDC-trained disease detectives across the globe.

Eradicating Polio: Polio cases have dropped more than 99% since 1988.

Measles and Rubella Elimination: Since the launch of the Measles & Rubella Initiative (M&RI) and during the period 2000-2019, more than 31.7 million measles deaths have been prevented through vaccination.

Provide Antiretroviral Treatment (ART): By the end of 2021, 11.7 million people were on ART as a result of CDC’s support of HIV care and treatment, through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Response.

Preventing a Leading Cause of Death: TB Preventive Treatment (TPT) significantly reduces (up to 70%) the chance of PLHIV from getting TB, a leading cause of death for PLHIV. Between 2018 and 2021 quarter 1, CDC supported 4.5 million of the 7.2 million PLHIV who received TPT globally, surpassing the global target of 6 million two years ahead of schedule.

Eliminating Parasitic Diseases: Scale up of proven interventions has led to:

- 649 million people no longer requiring treatment for lymphatic filariasis

- Just 27 human cases of Guinea worm disease in 2020

- 1.38 billion people no longer requiring treatment for trachoma

Reducing Malaria Deaths: CDC and global partners have helped save more than seven million lives and prevented more than one billion cases of malaria since 2000.

The Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) educates international field epidemiologists, or “disease detectives” to be “boots on the ground” on the front lines when and where infectious disease events occur. Epidemiologists trained through FETP focus on investigating, containing, and eliminating outbreaks before they become larger threats. Since 2015, CDC has focused on expanding access to the FETP program to include more than 80 countries and trained more than 19,000 graduates.

Guinea, along with other countries in the region, had a shortage of experienced field epidemiologists during the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic. To address this shortage, and as part of preparedness planning done in partnership with the Government of Guinea following the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak there, CDC worked with the Ministry of Health to establish an FETP program in 2017. Since that time, Guinea’s FETP has trained nearly 200 disease detectives. Today, Guinea is better prepared to respond to outbreaks, conduct disease investigations, and manage and analyze data thanks in part to the FETP program.

An FETP resident looking for Ebola contacts in a community in Guinea during the 2021 Ebola outbreak. Credit: Salomon Corvil/CDC.

For example, during the recent 2021 Ebola outbreak in Guinea, FETP-trained disease detectives held key surveillance and response positions. They were among those who responded to the first Ebola case, helping to quickly contain the spread of the disease. These epidemiologists isolated suspect cases and identified contacts to help keep others from becoming sick. They also led data management and Ebola vaccination activities. FETP graduates improved response timeliness and quality. Equipped with new tools including a vaccine, FETP graduates contributed to a significant reduction of geographic spread, duration, cases, and deaths when compared to the previous Ebola outbreak.

Africa CDC, based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with five regional collaborating centers, coordinates continent-wide response outbreak efforts including responses to Ebola and COVID-19. Credit: Africa CDC.

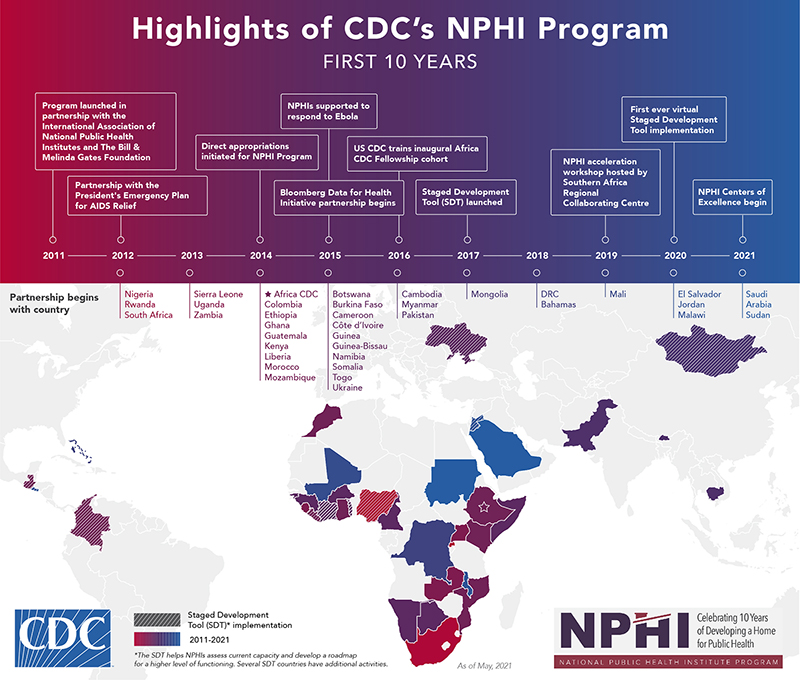

Since 2011, CDC has worked to develop and strengthen National Public Health Institutes (NPHI) in more than 30 countries. Similar to the role that CDC plays in the United States, NPHIs are government-based agencies that organize and link a country’s public health activities providing coordinated national leadership for public health. CDC’s NPHI Program provides technical assistance, guidance, and support to countries developing new NPHIs or strengthening existing ones. Over the past decade, the program has worked with more than 30 countries, linking with critical organizations such as PEPFAR, the World Bank, WHO, Africa CDC, and many others.

The COVID-19 pandemic has overloaded public health systems worldwide. Countries without a centralized coordination point for scientific expertise and public health systems tend to be less effective and efficient during a public health emergency.

Burkina Faso did not hesitate in its COVID-19 response, even though its National Public Health Institute (NPHI), or L’Institut National de Santé Publique (INSP), and the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) were still in their infancy at the start of the pandemic. Established in 2018 with support from the U.S. CDC, INSP and its EOC have played an essential role in tackling the outbreak. As the virus continued to spread worldwide, Burkina Faso activated its EOC, developed a COVID-19 management plan, and created a pandemic taskforce.

The country’s effective management of the COVID-19 response is due to several factors, including capacity building that was initiated prior to the current crisis and a focus on public health emergency management through INSP.

CDC first began collaborating with the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso in 1991. The initial technical support for polio eradication expanded to include other vaccine preventable diseases such as measles and meningitis. With the launch of the Global Health Security Agenda, CDC established an office in Burkina Faso in 2016 focused on strengthening the country’s ability to prevent, detect, and respond to public health threats, and to strengthen the country’s capacity in surveillance, laboratory systems, workforce development, and emergency management.

Dr. Kader Ilboudo working with the National Influenza Reference Laboratory collecting a COVID-19 specimen sample during the early stages of the outbreak in Burkina Faso. Credit: Emilie Thérèse Dama/CDC Burkina Faso.

The Global Emergency Alert and Response Service (GEARS) combines the critical functions of the Global Disease Detection Operations Center (GDDOC) and the Global Rapid Response Team (GRRT) into a “one stop shop” that allows for a seamless transition between disease detection and response activities. GRRT identifies and deploys expert CDC staff within 72 hours of receiving a deployment request.

To support the response to President Biden’s Operation Allies Welcome (OAW) Initiative, GRRT identified and deployed 12 skilled CDC staff to the eight facilities established by the Department of Homeland Security. Deployed staff collaborated with other U.S. agencies to set-up COVID-19 testing and vaccination clinics and systems to monitor and track potential spread of infectious diseases, including measles. GRRT provided immediate support to the operation while also continuing to support CDC’s response to the earthquake in Haiti, deployments for COVID-19 International Task Force, and recurring outbreaks of vaccine derived poliovirus and Ebola around the world.

Mary Claire Worrell (left) and Christine Atherstone (right) deployed to Joint Base McGuire, Dix, and Lakehurst (JB-MDL), where they established a disease surveillance system in early September in response to a case of measles confirmed in a person who evacuated from Afghanistan. Credit: Dr. Patricia Walker/International SOS.

CDC, as part of PEPFAR, works in collaboration with host country governments and with Columbia University and the University of Maryland to develop and implement population-based HIV household surveys. These surveys provide data for focusing HIV program resources and tracking progress. The survey in Nigeria found that less than half of the 1.9 million people living with HIV were receiving lifesaving HIV treatment. Using this data, CDC and partners focused on a dramatic, targeted scale up of HIV treatment to put Nigeria on the path to epidemic control.

Efforts focused on rolling out an HIV anti-retroviral therapy (ART) surge in the nine Nigerian states with the largest numbers of individuals with HIV not receiving treatment. CDC efforts also included expanded testing. CDC and partners established incident command structures in each state and used a CDC-designed strategic operational platform to facilitate efforts. Experts collected and analyzed site-level data each week. They used the data to adapt approaches in the hard-hit communities.

A young person gets an HIV test at an open-air testing site in the Rivers State, Nigeria. Credit: CDC Nigeria Country Team.

The first 18-months of the Nigeria HIV treatment Surge resulted in an eight-fold increase in the weekly number of newly identified people with HIV who started treatment in the nine focal states, even amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The total number of people diagnosed with HIV who are now receiving treatment in those states also saw a 65 percent increase in a year and a half. Based on this initial success, CDC worked with partners to expand efforts to nine additional states. As of 2021, the Nigeria HIV treatment surge is now serving 903,000 PLHIV in 18 states, compared to 454,000 in 2019.

While these gains are significant, work remains. In Nigeria and other places throughout the world, many people remain unaware of their HIV status. To reach epidemic control, efforts to find people living with HIV, link them to treatment, retain them on HIV treatment, and help them sustain viral suppression are essential. In order for the program to continue, it counts on the integral skills of community health workers and the potential to be replicated in other settings.

Malaria has killed billions of people globally over the centuries. Several decades after endemic malaria transmission was eliminated in the United States, nearly half the world’s population still lives in areas at risk of malaria transmission. In 2020, malaria was responsible for the deaths of an estimated 627,000 people—mostly children under the age of five in sub-Saharan Africa.

CDC is a global leader in providing scientific expertise to endemic countries and partners to improve surveillance, laboratory systems, and management of malaria cases. CDC co-implements the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) with USAID in 24 African countries and three programs in the Greater Mekong sub-Region. CDC provides technical leadership and advice to the U.S. Global Malaria Coordinator on surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, and operational research, to drive progress toward malaria elimination.

A household survey team heading out to a study village on an island in Lake Victoria, Kenya to assess the feasibility, coverage, uptake of the malaria vaccine and the effect of vaccine introduction on other child health interventions. Credit: Eunice Radiro/KEMRI/CDC.

One of the most important and exciting public health developments of the year 2021 was the approval of the first malaria vaccine. On October 6th, the WHO recommended the RTS,S malaria vaccine for broader use among children in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions with moderate to high malaria transmission. CDC’s parasitic diseases and malaria program was instrumental in accomplishing this milestone.

CDC’s years of collaborative work, including with the RTS,S pilot introduction in Kenya, contributed to the WHO recommendation and helped pave the way for wide scale implementation of this promising new intervention.

“RTS,S is the first malaria vaccine to reach this stage and is likely the best new widely implementable tool to combat malaria since artemisinin-based combination therapy and bed nets,”

In Kenya, where malaria is still one of the leading killers of young children, the new vaccine has the potential to save thousands of lives.

CDC’s role in helping to co-implement PMI across Africa and the Mekong Delta region is saving lives, while helping to increase understanding of how to safely deliver malaria control interventions. CDC provides specific technical guidance to Health Ministries and WHO, to maintain essential services for malaria in low-resource countries, and to inform the global malaria community on the provision of safe and accessible malaria care and tools in the most affected countries.

Over decades, CDC-supported or tested malaria interventions such as bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and rapid diagnostics tests, paired with the improved availability of antimalarial drugs have helped drive down malaria cases and deaths. Since 2000, 1.5 billion cases of malaria and 7.6 million deaths have been averted, but much work remains to eliminate malaria as a perennial public health threat that continues to sicken and take the lives of so many across the world.

CDC works with global partners to control, eliminate, and eradicate neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). CDC works to reduce the substantial illnesses and disability caused by NTDs, with a focus on those that can be controlled through mass drug administration or other low-cost interventions. CDC’s program focuses on diseases including lymphatic filariasis (LF or elephantiasis), onchocerciasis (river blindness), blinding trachoma, schistosomiasis, three soil-transmitted helminths (intestinal worms), and Guinea worm disease.

Lymphatic filariasis is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide. Over 50 million people across 72 countries are afflicted with LF. In addition to causing extreme physical disfigurement, LF results in stigmatization and socio-economic challenges. Affected people frequently cannot work or conduct normal daily activities, crippling both their families and their communities.

American Samoa is the last remaining known American territory with ongoing LF transmission. CDC works with partners, particularly the American Samoa Department of Public Health, to carry out LF elimination strategies recommended by WHO. These include distributing preventative medicines to communities through mass drug administration campaigns and regularly assessing the impact of disease transmission.

CDC works closely with the American Samoa Department of Public Health and other partners to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in American Samoa, the last U.S. territory with known transmission of the neglected tropical disease. In this photo, school children check in to take preventive medicines during a round of mass drug administration. Credit: Kimberly Won/CDC.

CDC and its partners assisted the American Samoa Department of Health to conduct one such campaign in the fall of 2019. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, CDC was not able to travel to American Samoa to assess its impact. Without a follow-up impact assessment, it is difficult to know how effective the mass drug administration was—or was not—in preventing LF infections. “If you miss an assessment, you delay reaching the endpoint: validation of elimination,” said CDC health scientist Kimberly Won. “It’s crucial to stick to the established timeline. Any deviation from the timeline of planned activities can cause delays in implementation of key program activities, risking falling short of LF elimination targets.”

So, CDC scientists innovated their approach, working remotely and training partners on the ground on key steps to conducting an assessment. “From CDC headquarters in Atlanta, we were able to train teams on how to move around villages in a systematically randomized way, how to administer questionnaires, how to collect blood samples, and how to treat discovered cases,” said epidemiologist Tara Brant describing how CDC worked with American Samoa Department of Public Health and the Pacific Island Health Officers Association to train American Samoa colleagues during the pandemic.

In October 2021, American Samoa Department of Health kicked off a third round of mass drug administration for LF using the WHO-recommended triple-drug regimen with remote technical support from CDC staff. CDC is planning a follow-up coverage survey that will occur in early 2022.

In early 2020, CDC’s global immunization program partnered with WHO to conduct measles risk assessments for high-risk countries. In Chad, the results showed that 1.2 million children under the age of five were at risk of measles. The assessment estimated that a mass vaccination campaign could close the dangerous immunity gap and mitigate the risk of a serious measles outbreak in Chad.

Based on the compelling data, presentation, and partner outreach, in September of 2020 the Chad Ministry of Health approved to move forward with a nationwide measles vaccination campaign. After a readiness assessment to ensure that adequate measures were in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the campaign took place in January and March of 2021.

To build awareness about the campaign and vaccine confidence, CDC partnered with the International Federation of Red Cross and the Chad Red Cross to conduct social mobilization activities that engaged parents, caregivers, and trusted community leaders. The successful campaign administered over 3.7 million measles doses, including full vaccination of over 43,000 children who had never received a single vaccine, known as zero-dose children. In 2021, Chad reported 2,348 measles cases – a sharp decline from previous years, further highlighting the campaign’s success.