Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People

COVID-19 Homepage

A Sort of Homecoming

Mitsuru Toda traveled halfway around the world for a career at CDC.

But when COVID-19 began sickening passengers on a cruise ship in the Pacific, her job as an epidemiologist took her back to her hometown.

Mitsuru grew up in the Japanese port city of Yokohama, where the cruise ship Diamond Princess docked in February after a passenger and more than a dozen crew members became ill with COVID-19. The 3,700 passengers and crew aboard were quarantined.

While the US Embassy and the State Department worked to bring home more than 300 Americans aboard the cruise liner, more than 100 who tested positive for the disease had to stay in Japan. Mitsuru and her team were sent to oversee those who tested positive until they could recover and return home.

The first big cluster outside of China

“This cruise ship was really the first big cluster that was outside China, so there was a lot of scrutiny,” Mitsuru says. “CDC specifically had to come up with guidelines for how to manage the remaining passengers.”

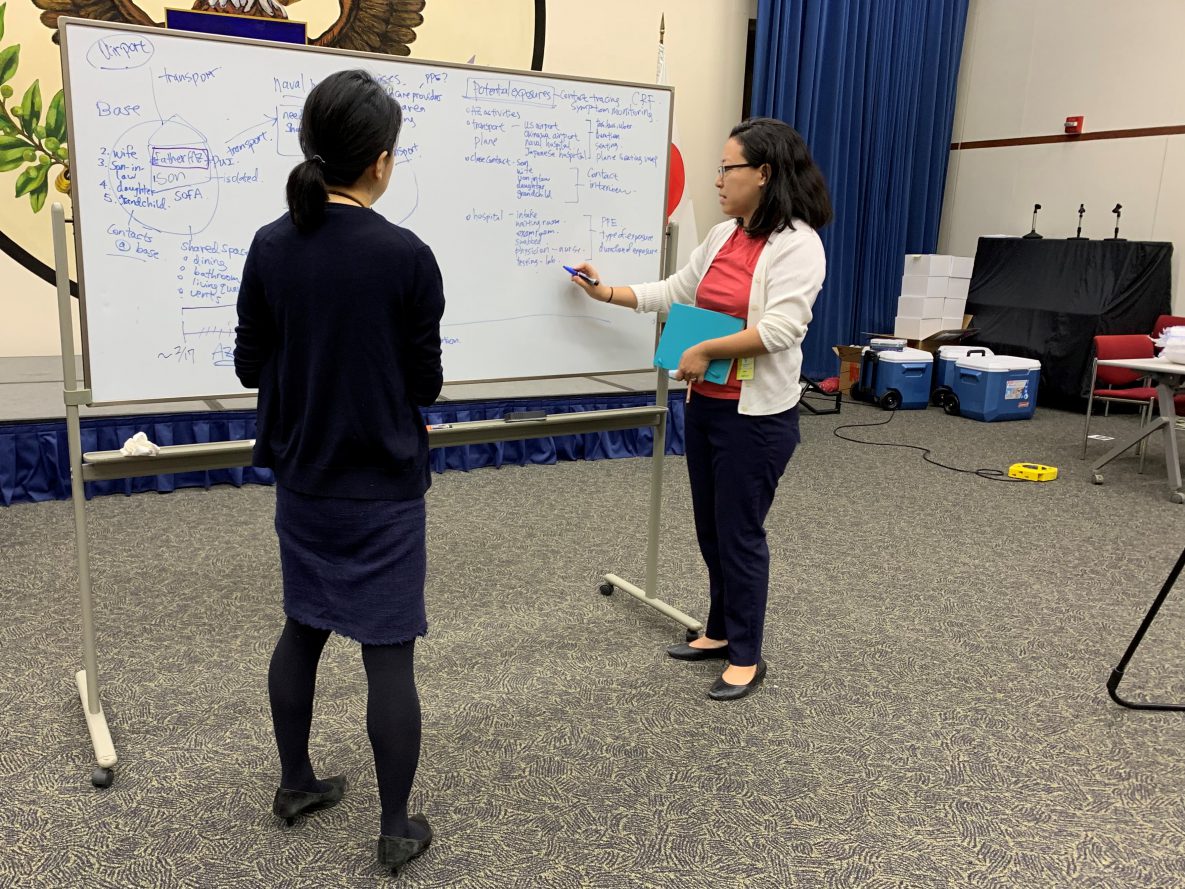

Mitsuru interviewed quarantined passengers to learn how they may have been exposed to the virus that causes the disease, when symptoms started, and how the disease progressed. Many of them were hospitalized, and some had family members who were ill.

“Some of them were critically sick, and family members were with them. It was a really distressing time,” Mitsuru says. However, “I was surprised how willing people were to talk to me and share their experiences on the ship. It was very early in the epidemic, so we learned a lot from this experience,” she says.

During her assignment in Yokohama, she was able to catch up with her family at her childhood home—but only for a few hours before she had to turn her attention back to the investigation. The information she gathered during her interviews was used to develop guidelines for when people on other ships could return home safely, without posing a risk to the public. The work “was really interesting, because it was sort of at the intersection of epidemiology, diplomacy, and policy,” she says.

In a way, what brought Mitsuru to the CDC in the first place was also an intersection of diplomacy and public health. She came to the United States as an undergraduate to study international relations. As a student, she traveled to places like Kenya and Peru, where issues of inequality and a lack of access to public health programs caught her attention. After that, “I tried to get as much exposure to science and research as possible,” she says.

‘You should be an EIS officer’

She got a master’s degree in public health from Harvard and went to work for Japan’s International Cooperation Agency. She earned a PhD in epidemiology from Japan’s Nagasaki University while working as a technical adviser to Kenya’s Ministry of Health, where she studied the use of text messaging to improve disease surveillance. And she got to know other international public health advisers—including some from CDC.

“The expatriate community is big, but also close-knit,” Mitsuru says. “Some of the people I became close to were ex-Epidemic Intelligence Service officers, and they said, ‘If you want to make a difference in public health, you should come to CDC and become an EIS officer.’ So I applied to EIS, thinking I would never get in, and I got in.”

She joined CDC full-time in 2019 after a two-year fellowship as an EIS officer, during which she specialized in pursuing outbreaks of fungal disease.

“It was such a unique opportunity to be able to work in Japan, not just as a native speaker but someone who grew up in Japan,” Mitsuru says. “I know my contribution was really small, but I am going to remember this for a very long time.”