Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report 2018 – Introduction

BACKGROUND

Hepatitis A is a vaccine-preventable, communicable disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). HAV is usually transmitted personto-person through the fecal-oral route or through consumption of contaminated food or water. Most adults and older children with hepatitis A have symptoms that usually resolve within 2 months of infection; most children less than 6 years of age do not have symptoms or have an unrecognized infection. Signs and symptoms associated with hepatitis A infection may include one or more of the following: fever, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, dark urine, and clay-colored stools. Hepatitis A is a self-limited disease that does not result in chronic infection. Treatment for HAV infection may include rest, adequate nutrition and fluids. Hospitalization may be required for more severe cases. The best way to prevent hepatitis A infection is to get vaccinated(1).

Hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable liver disease caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). HBV is transmitted when blood, semen, or another body fluid from a person infected with the virus enters the body of someone who is not infected. This can happen through sexual contact; sharing needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment; or from mother to baby at birth. For some people, hepatitis B is an acute, or short-term, illness but for others, it can become a long-term, chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis B can lead to serious health issues, including cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death. There are treatments but no cure for hepatitis B. The best way to prevent hepatitis B is by getting vaccinated(2,3).

Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV is a blood-borne virus. Today, most people become infected with HCV by sharing needles or other equipment to inject drugs(4). For some people, hepatitis C is a short-term illness but for more than 50% of people who become infected with the hepatitis C virus, it becomes a long-term, chronic infection(5). Like chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C is a serious disease that can result in cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death. Many people might not be aware of their infection because they are not clinically ill. Since 2013 there have been highly effective, well-tolerated cures for hepatitis C . There is no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C (6). The best way to prevent hepatitis C is by avoiding behaviors that can spread the disease, especially injecting drugs.

Key facts about hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C

| Hepatitis A | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main route(s) of transmission | Fecal-oral | Blood, sexual | Blood |

| Incubation Period | 15–50 days (average: 28 days) |

60–150 days (average: 90 days) |

14–182 days (average range: 14–84 days) |

| Symptoms of Acute Infection | Symptoms of all types of viral hepatitis are similar and can include one or more of the following: jaundice, fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, joint pain, dark urine, clay-colored stool, diarrhea (hepatitis A only) | ||

| Perinatal transmission | No | Yes | Yes |

| Vaccine available | Yes | Yes | No |

| Treatment | Supportive care | Yes, not curative | Yes, curative |

NATIONAL PROFILE OF VIRAL HEPATITIS, 2018

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collects, analyzes, and disseminates surveillance data on viral hepatitis. Each week, health departments submit cases of viral hepatitis to the CDC through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). The annual surveillance report, published by the Division of Viral Hepatitis, summarizes information about reported cases of hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C and deaths with either of these hepatitides listed as a cause of death in CDC’s National Vital Statistics System (NVSS). These surveillance data are used by public health partners to help focus prevention efforts, plan services, allocate resources, develop policy, and detect and respond to clusters of viral hepatitis infection.

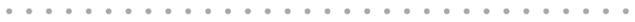

In 2018, 12,474 hepatitis A cases were submitted to CDC, resulting in 24,900 estimated infections (95% CI: 17,500–27,400) after adjusting for case under-ascertainment and under-reporting (see Technical Notes)(7). The reported case count corresponds to a rate of 3.8 cases per 100,000 population, a nearly 850% increase from the reported incidence rate of 0.4 cases per 100,000 population in 2014. This increase was primarily driven by widespread person-to-person outbreaks of hepatitis A that are unprecedented since the introduction of the hepatitis A vaccine. These outbreaks are primarily occurring among people who use drugs and people experiencing homelessness, resulting in prolonged community outbreaks in several states that have been difficult to control. Over 55% of hepatitis A cases reported to CDC in 2018 occurred among persons aged 30–49 years. Among the 8,471 (68%) reported cases that included risk information for injection drug use, 4,247 (50%) reported injection drug use. A total of 6,292 case-patients were hospitalized (58% hospitalization rate among those with hospitalization information available).

Data from death certificates filed in the vital records office of the 50 states and the District of Columbia found that the age-adjusted death rate associated with hepatitis A in 2018 among U.S. residents was 0.05 deaths per 100,000 population, which is more than double the rate of 0.02 deaths per 100,000 population in 2017(8).

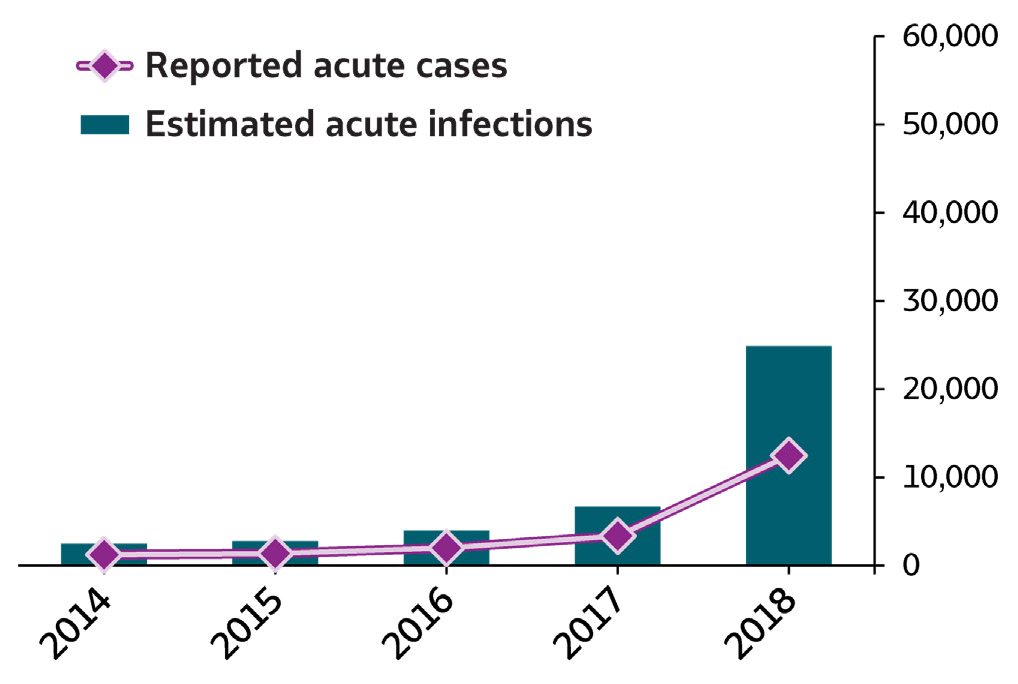

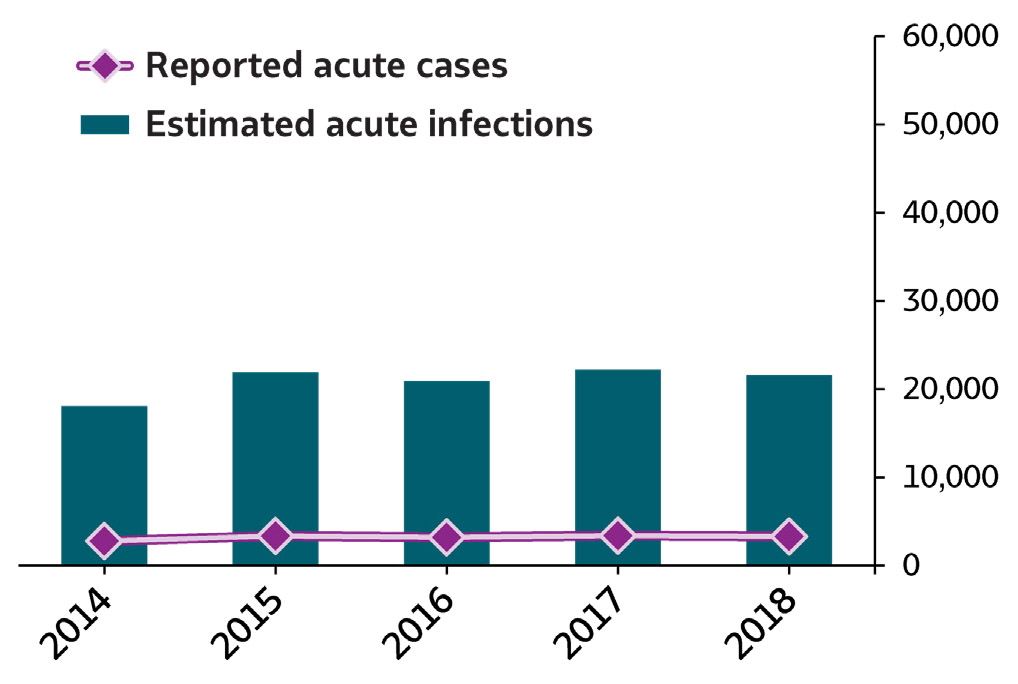

Reported cases of acute hepatitis B declined after routine vaccination of children was recommended in 1991 and became relatively stable from 2010 through 2018. In 2018, a total of 3,322 acute hepatitis B cases were reported to CDC, resulting in 21,600 estimated infections (95% CI: 12,300–52,800) after adjusting for case under-ascertainment and under-reporting (see Technical Notes)(7). The reported case count corresponded to a rate of 1.0 cases per 100,000 population. Over half of acute hepatitis B cases reported to CDC in 2018 occurred among persons aged 30–49 years. Among the 1,518 (46%) reported acute cases that included risk information for injection drug use, 549 (36%) reported injection drug use. A total of 1,483 case-patients with acute hepatitis B were hospitalized (62% hospitalization rate among those with hospitalization information available).

Data from death certificates filed in the vital records office of the 50 states and the District of Columbia found that the age-adjusted death rate associated with hepatitis B in 2018 among U.S. residents was 0.43 deaths per 100,000 population, which decreased slightly from 0.46 deaths per 100,000 population in 2017(9). Among 28 jurisdictions with data available, hepatitis B-associated death rates increased in 11 jurisdictions from 2017 to 2018.

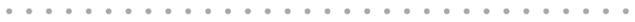

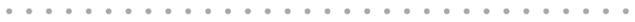

In 2018, 3,621 acute hepatitis C cases were reported to CDC, resulting in 50,300 estimated infections (95% CI: 39,800–171,600) after adjusting for case under-ascertainment and under-reporting (see Technical Notes)(7). The reported acute hepatitis C case count corresponds to a rate of 1.2 cases per 100,000 population, an over 71% increase from the reported incidence rate of 0.7 cases per 100,000 population in 2014. Over 65% of acute hepatitis C cases reported to CDC in 2018 were among persons aged 20–39 years. Among the 1,535 (42%) reported acute cases that included risk information for injection drug use, 1,102 (72%) reported injection drug use. A total of 850 case-patients with acute hepatitis C were hospitalized (44% hospitalization rate among those with hospitalization information available).

There were 214 perinatal hepatitis C cases reported to CDC in 2018, which is the first year that standardized surveillance for perinatal hepatitis C was conducted by states and case notifications submitted to CDC.

Data from death certificates filed in the vital records office of the 50 states and the District of Columbia found that the age-adjusted death rate for hepatitis C in 2018 was 3.72 deaths per 100,000 population, representing a nearly 26% decrease from the mortality rate in 2014 (5.01 deaths per 100,000 population)(9). Despite this improvement, hepatitis C-associated death rates increased in 15 jurisdictions from 2017 to 2018.

TECHNICAL NOTES

Case ascertainment and case reporting

For a health department to report cases of viral hepatitis to the CDC, they must have systems and processes in place that ensure each case is detected. Due to varying state laws, resources, and infrastructure, not all health departments report all cases of acute or newly identified chronic viral hepatitis to the CDC. In addition, it is not possible to diagnose every acute case, because symptoms may be either so mild that the person does not seek care or too vague to prompt a health care provider to suspect and test for viral hepatitis.

Case reporting generally begins when a local or state health department receives a positive laboratory report, indicating an individual has a viral hepatitis infection. Since initial reporting provides limited information and clinical symptoms are frequently needed to classify cases as acute, reported cases may require extensive follow-up to obtain full information for establishing case status and case classification.

Health departments prioritize cases for follow-up using their own protocols and may submit cases to CDC with incomplete or missing information. Additionally, the volume of laboratory reports for chronic viral hepatitis infections may be so large that not all health departments are able to consistently detect and report all chronic cases to the CDC; in 2018, only 14 states (Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Ohio, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia) received federal funding to support viral hepatitis surveillance. Under-reporting results in an underestimation of chronic viral hepatitis cases when using state reports based on data from NNDSS. Data on chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C are in this report where available; however, these are newly identified chronic cases and do not measure prevalence.

All viral hepatitis conditions with no reported cases or characterized as “Not Reportable” or “Data Unavailable” for 2018 in a jurisdiction’s final signed report to CDC’s National Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services (CSELS) were reported according to the following notation used by CSELS:

N : Not reportable. The disease or condition was not reportable by law, statute, or regulation in the reporting jurisdiction.

U : Unavailable. The data are unavailable.

Case definitions

To ensure consistent reporting across states, the Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), in collaboration with CDC, developed case definitions for viral hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The case definitions facilitate standardized reporting using uniform criteria and differentiate between acute, chronic, and perinatal cases. When new technologies are developed for laboratory testing or better clinical data becomes available, the case definitions are updated. Changes to case definitions should be considered when examining trends over time. For more information on 2018 case definitions, visit the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System’s website. There were no changes to case definitions implemented for acute or chronic viral hepatitis in 2018; however, the first case definition for perinatal hepatitis C was implemented in 2018.

Estimating incidence of acute viral hepatitis

To account for under-ascertainment and under-reporting, a probabilistic model to estimate the true incidence of acute hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C from reported cases has been published previously(7). The model includes the probabilities of symptoms, referral to care and treatment, and rates of reporting to local and state health departments. The published multipliers have since been corrected by CDC to indicate that each reported case of acute hepatitis A represents 2.0 estimated infections (95% bootstrap confidence interval [CI]: 1.4–2.2); each reported case of acute hepatitis B represents 6.5 estimated infections (95% bootstrap CI: 3.7–15.9); and each reported case of acute hepatitis C represents 13.9 estimated infections (95% bootstrap CI: 11.0–47.4).

Mortality surveillance

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) provides information on deaths that occur in the United States. NVSS data in this report are from the 2014–2018 Multiple Cause of Death files on the CDC WONDER online database(9). These data are based on information from all death certificates filed in the vital records offices of the 50 states and the District of Columbia through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Deaths of nonresidents (e.g., nonresident aliens, nationals living abroad, residents of U.S. Territories) and fetal deaths are excluded.

SUMMARY 2018

Viral Hepatitis Acute Infections

Reported in 2018

(17,500 – 27,400)*

Estimated in 2018

Reported in 2018

(12,300 – 52,800)*

Estimated in 2018

Reported in 2018

(39,800 – 171,600)*

Estimated in 2018

*95% Bootstrap Confidence Interval

REFERENCES

- Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020;69(No. RR-5):1–38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1.

- Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2018;67(No. RR-1):1–31. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B questions and answers for health professionals. May 16, 2019. Accessed February 3, 2020; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq.htm.

- Zibbell JE, Asher AK, Patel RC, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis C virus infection related to a growing opioid epidemic and associated injection drug use, United States, 2004 to 2014. Am J Public Health 2018;108:175–

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: hepatitis C virus infections among young adults—rural Wisconsin, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:358.

- Seifert LL, Perumpail RB, Ahmed A. Update on hepatitis C: direct-acting antivirals. World J Hepatol 2015;7: 2829–33.

- Klevens RM, Liu, S, Roberts H, et al. Estimating acute viral hepatitis infections from nationally reported cases. Am J Public Health 2014;104(3):482– Available from PubMed Central PMCID PMC3953761.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance—United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2017surveillance/index.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- CDC WONDER dataset documentation and technical methods can be accessed at https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html#.

OTHER SOURCES

- Doshani M, Weng M, Moore KL, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices: Use of hepatitis vaccine for persons experiencing homelessness. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(6):153–156. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6806a6.htm.

- Mast EE, Margolis H, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-16):1–33; quiz CE1-4.

- Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005;54(RR-16):1–31.

- Thomas DL, Sweeff LB. Natural history of hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis 2005;9:383–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2005.05.003.