Food Safety

CDC estimates that each year, roughly 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) gets sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die due to foodborne diseases.1 Risk for infection and severity varies at different ages and stages of health.4

Diseases spread by contaminated foods continue to challenge the public health system. Bacteria, viruses, parasites, and chemicals can cause foodborne diseases, which can vary from mild to fatal.1 Robust surveillance for these diseases is essential for detecting outbreaks. It also provides critical information to food regulatory agencies and the food industry so that appropriate control and preventive measures can be implemented.2

The Prevention Status Reports (PSRs) highlight—for all 50 states and the District of Columbia—the status of select practices that can help states prevent or reduce foodborne illness. These practices include

- Increasing the speed of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) testing of reported Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157 cases

- Increasing the completeness of PFGE testing of reported Salmonella cases

These practices have been recommended by the Council to Improve Foodborne Outbreak Response on the basis of scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness in improving foodborne disease surveillance and detection.3

Policies & Practices

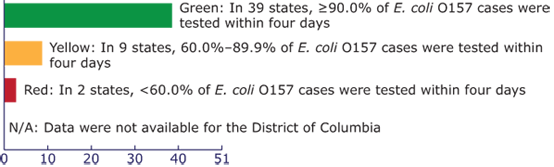

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE, is a technique used to distinguish between strains of organisms at the DNA level. Speed of PFGE testing is defined as the annual proportion of E. coli O157 PFGE patterns reported to CDC (i.e., uploaded into PulseNet, the CDC-coordinated national molecular subtyping network for foodborne disease surveillance) within four working days of receiving the isolate in the state public health PFGE lab.

The CDC Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement provides federal funding to states and establishes a national performance target of testing 90% of reported E. coli O157 cases within four days. Performing DNA fingerprinting as quickly as possible for all Shiga toxin-producing E. coli improves detection of outbreaks. Rapid outbreak detection can help prevent additional cases and can help identify control and prevention measures for food regulatory agencies and the food industry.2

Status of the speed of PFGE testing of reported E. coli O157 cases, United States (2011)

Note: Data corrected February 10, 2015.

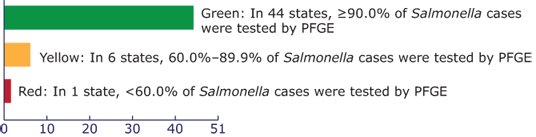

Completeness of PFGE testing of reported Salmonella cases

Completeness of PFGE testing of reported Salmonella cases is defined as the annual proportion of Salmonella cases reported to CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) with PFGE patterns uploaded into PulseNet. Research and experts in the field agree that performing DNA fingerprinting of all Salmonella cases would improve detection of outbreaks.2

Status of the completeness of PFGE testing of reported Salmonella cases, United States (2011)

(State count includes the District of Columbia.)

Prevention Status Reports: Food Safety, 2013

The files below are PDFs ranging in size from 100K to 500K. ![]()

Note: An erratum for the indicator entitled “Speed of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) testing of reported E. coli O157 cases,” has been published for North Carolina.

References

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011;17:7–15.

- Council to Improve Foodborne Outbreak Response. Guidelines for Foodborne Disease Outbreak Response. Atlanta, GA: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; 2009.

- Lund BM, O’Brien SJ. The occurrence and prevention of foodborne disease in vulnerable people. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 2011;8:961–73.

- Scallan E, Griffin FM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—unspecified agents. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011;17:16–22.

Email Updates

Email Updates STLT Connection

STLT Connection What's New

What's New STLT Collaboration Space

STLT Collaboration Space Field Notes

Field Notes Contact CSTLTS

Contact CSTLTS