Teen Pregnancy

Teen mothers are more likely to experience negative social outcomes than teens who do not have children. Children of teens are more likely to achieve less in school, experience abuse or neglect, have more health problems, be incarcerated at some time during adolescence, and give birth as a teenager.3

Each year in the United States, about 750,000 women under age 20 become pregnant.1 In 2011, approximately 330,000 teens 15-19 years of age gave birth.2

The Prevention Status Reports highlight—for all 50 states and the District of Columbia—the status of a key policy that states can use to prevent teen pregnancy:

This policy is consistent with recommendations in the US Department of Health and Human Services’ National Prevention Strategy to expand access to contraceptive services4 and with the Healthy People 2020 objective to “increase the number of States that set the income eligibility level for Medicaid-covered family planning services to at least the same level used to determine eligibility for Medicaid-covered, pregnancy-related care” (Objective FP-14).5

Policies & Practices

Expansion of state Medicaid family planning eligibility

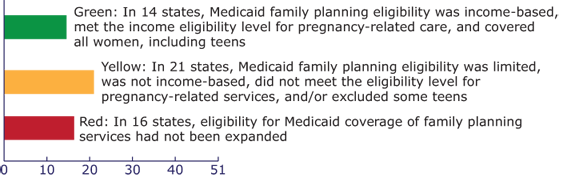

Healthy People 2020 sets a target of increasing the number of states that set the income eligibility level for Medicaid coverage of family planning services to at least the same level used to determine Medicaid eligibility for pregnancy-related care (the level varies by state).5 This expansion of coverage would decrease the number of pregnancies, births, and abortions among teens, and increase the number of dollars saved, in each state.6-11

States can expand eligibility for Medicaid coverage of family planning services to include teens under age 18 years by 1) securing approval (officially known as a “waiver” of federal policy) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2) amending the state Medicaid plan with a State Plan Amendment (i.e., a permanent change to the state’s Medicaid program), or 3) expanding the full state Medicaid program.

By 2014, more states will expand the full Medicaid program in accordance with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.12 As a result, the use of family planning waivers and state plan amendments will be used together with the expansion of many state Medicaid programs. However, given the experience in Massachusetts13–15 with full expansion, CDC recommends that states retain family planning waivers and state plan amendments for several years after 2014 to maximize access to care during this transitional period.

Status of expansion of state Medicaid family planning eligibility, United States (as of August 2013)

(State count includes the District of Columbia.)

Prevention Status Reports: Teen Pregnancy, 2013

The files below are PDFs ranging in size from 100K to 500K. ![]()

*This report was updated on 4/16/14 to correct a data error to the graph, “Proportion of currently sexually active high school students who used a condom during last sexual intercourse.”

References

- Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, et al. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990–2008[PDF 463K]. National Vital Statistics Reports 2012;60(7).

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: final data for 2011[PDF 1.6M]. National Vital Statistics Reports 2013;62(1).

- Hoffman S, Maynard R, eds. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2008.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Prevention Strategy: America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness[PDF 4.7M]. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Family planning. In: Healthy People 2020. Updated Sep 6, 2012.

- Sonfeld A, Frost J, Gold R. Estimating the impact of expanding Medicaid eligibility for family planning services: 2011 update[PDF 2.1M]. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2011.

- Foster DG, Biggs MA, Rostovtseva D, et al. Estimating the fertility effect of expansions of publicly funded family planning services in California. Women’s Health Issues 2011;21:418-24.

- Yang Z, Gaydos LM. Reasons for and challenges of recent increases in teen birth rates: a study of family planning service policies and demographic changes at the state level. Journal of Adolescent Health 2010;46:517-24.

- Kearney MS, Levine PB. Subsidized contraception, fertility, and sexual behavior. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2009;91(1):137–51.

- Lindrooth RC, McCullough JS. The effect of Medicaid family planning expansions on unplanned births[PDF 296K] . Women’s Health Issues 2007;17:66–74.

- Edwards J, Bronstein J, Adams K. Evaluation of Medicaid Family Planning Demonstrations. The CNA Corporation, CMS Contract No 752-2-415921:22; Nov 2003.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Insurance Marketplace. Accessed Aug 5, 2013.

- Dennis A, Blanchard K, Cordova D, et al. What happens to the women who fall through the cracks of health care reform? Lessons from Massachusetts. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 2013;38(2):393–419.

- Dennis A, Clark J, Cordova D, et al. Access to contraception after health care reform in Massachusetts: a mixed-methods study investigating benefits and barriers. Contraception 2012;85(2):166–72.

- Levy AR, Bruen BK, Ku L. Health care reform and women’s insurance coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening. Preventing Chronic Disease 2012;9:E159.

Email Updates

Email Updates STLT Connection

STLT Connection What's New

What's New STLT Collaboration Space

STLT Collaboration Space Field Notes

Field Notes Contact CSTLTS

Contact CSTLTS