Antibiotic Use in the United States, 2017: Progress and Opportunities

What Do We Know About Antibiotic Use in Outpatient Settings?

| Age group | All Conditions* | Acute respiratory conditions** |

|---|---|---|

| 0-19 year olds | 29% | 34% |

| 20-64 year olds | 35% | 70% |

| ≥65 year olds | 18% | 54% |

| All ages | 30% | 50% |

*All conditions included acute respiratory conditions, urinary tract infections, miscellaneous bacterial infections, and other conditions.

**Acute respiratory conditions included ear infections, sinus infections, sore throats, pneumonia, acute bronchitis, bronchiolitis, upper respiratory infections (i.e., common colds), influenza, asthma, allergy, and viral pneumonia.

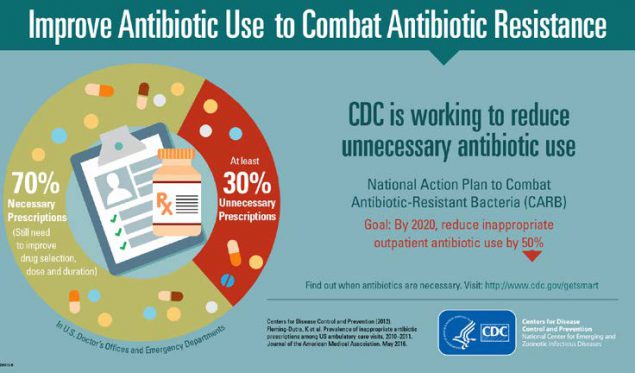

Each year, there are 47 million unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions written in U.S. doctors’ offices and emergency departments.7 Most of these unnecessary prescriptions are for respiratory conditions most commonly caused by viruses (including common colds, viral sore throats, and bronchitis) which do not respond to antibiotics, or for bacterial infections that do not always need antibiotics (like many sinus and ear infections). CDC estimated that at least 50 percent of antibiotic prescriptions for these acute respiratory conditions are unnecessary.8–10 These excess prescriptions each year put patients at needless risk for reactions to drugs or other problems, including C. difficile infections. In 2011 alone, one-third of the nearly 500,000 C. difficile infections in the United States were community-associated, or happening in patients who had no recent overnight stay in a healthcare facility.1–4

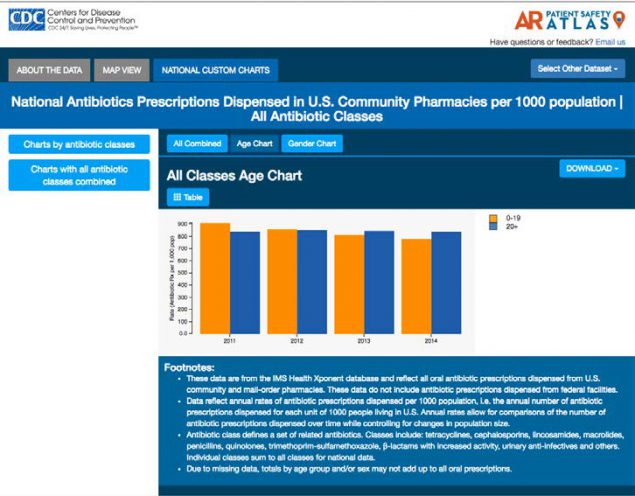

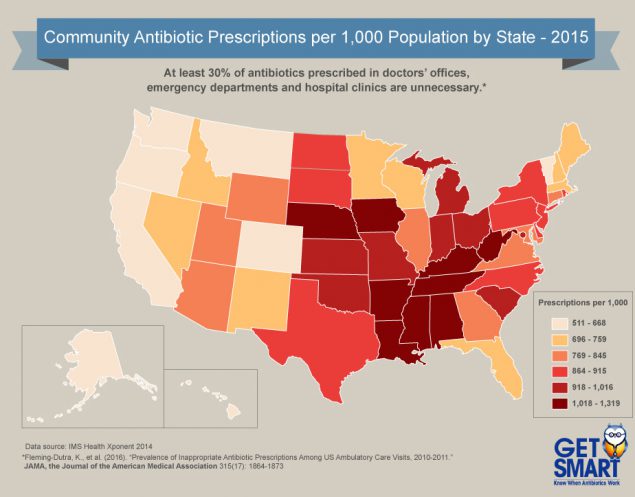

The good news is that antibiotic prescribing nationally has improved with a five percent decrease from 2011 to 2014. However, while there have been noticeable declines in antibiotic prescribing in children (0–19) (the population targeted by the Get Smart program) from 75 million prescriptions in 2011 to about 64 million prescriptions in 2014, antibiotic prescription rates for adults have risen slightly from about 192 million in 2011 to 198 million in 2014. Children under two and adults 65 and older still receive the most antibiotic prescriptions. Data also show that antibiotics are prescribed more frequently in states in the Southern and

Appalachian regions.

Prescribing the correct antibiotic is another area that requires attention. A CDC and Pew Charitable Trusts study found among outpatient visits in 2010– 2011, when an antibiotic was needed, patients were often prescribed an antibiotic not recommended by current clinical guidelines. For example, for sinus and middle ear infections and sore throats, recommended first-line antibiotics were only used half (52 percent) of the time.11

Percent of Patients Receiving The Recommended First-Line Antibiotic by Condition, United States, 2010-2011*

| Condition | Adults (20+ years of age) |

Children (0–19 years of age) |

|---|---|---|

| Sinus infection | 37% | 52% |

| Pharyngitis (sore throat) | 37% | 60% |

| Middle ear infection | n/a | 67% |

*Based on the prevalence of allergy to first-line antibiotics and estimated treatment failures after first-line antibiotics, at least 80% of patients presenting with these conditions should receive first-line antibiotics. Analysis is based on NAMCS and NHAMCS data.

CDC’s Antibiotic Resistance Patient Safety Atlas contains data on antibiotic prescriptions dispensed in outpatient pharmacies per 1,000 people. This interactive database provides information on how antibiotic prescribing varies by state, age group, and over time from 2011–2014.

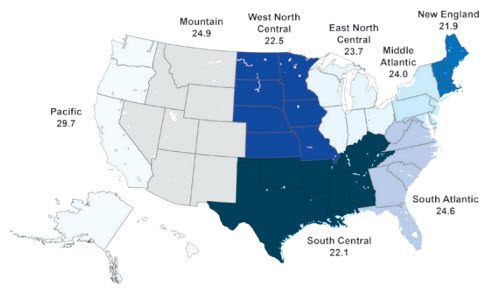

Avoidance of antibiotic treatment in adults with acute bronchitis (average), by Census division, 2008–2012

CDC experts found that healthy adults with acute bronchitis only received the right treatment—meaning they did not get an antibiotic—just over 20 percent of the time. This shows that nearly 80 percent of the time, patients were getting an antibiotic unnecessarily.

Oral Antibiotic Prescribing by Provider Type in the United States In 2014

| Provider type | Number of antibiotic prescriptions in 2014 (millions) |

|---|---|

| Family Practice Physicians | 58.1 |

| Physician Assistants & Nurse Practitioners | 54.4 |

| Internal Medicine | 30.1 |

| Pediatricians | 25.4 |

| Dentistry | 24.9 |

| Surgical Specialties | 19.9 |

| Emergency Medicine | 14.2 |

| Dermatology | 7.6 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 6.6 |

| Other | 25.0 |

| All Providers | 266.1 |

Commitment

Demonstrate dedication to and accountability for optimizing antibiotic prescribing and patient safety.

Action for Policy And Practice

Implement at least one policy or practice to improve antibiotic prescribing, assess whether it is working, and modify as needed.

Tracking and Reporting

Monitor antibiotic prescribing practices and offer regular feedback to providers, or have providers assess their own antibiotic prescribing practices themselves.

Education and Expertise

Provide educational resources to providers and patients on antibiotic prescribing, and ensure access to needed expertise on optimizing antibiotic prescribing.

CDC collaborates with partners to implement appropriate antibiotic use efforts at a local level. CDC funds and supports many state and local health departments and other partners across the country to implement targeted antibiotic stewardship improvements in outpatient settings.

Illinois Department of Public Health: Precious Drugs and Scary Bugs

In 2015, the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) developed the Precious Drugs and Scary Bugs program to improve the appropriate use of antibiotics, particularly for acute respiratory infections, in primary care, urgent care, and community health centers. IDPH asked healthcare providers to:

- Display a poster in exam rooms stating their commitment to appropriate antibiotic prescribing.

- Participate in educational webinars.

- Track their antibiotic prescribing data.

- Complete baseline and follow-up surveys.

Thirty-eight outpatient practices participated representing 239 healthcare providers. More than 500 commitment posters were printed and distributed. Participating healthcare providers reported that the poster improved communication, addressed patient expectations regarding antibiotics for acute respiratory infections, and reinforced a uniform message.

New York State Department of Health: Commitments to Appropriate Antibiotic Prescribing

In 2016, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) offered a “Get Smart Guarantee” poster [PDF – 1 page] for healthcare providers to pledge to only prescribe antibiotics when they are needed. The “Guarantee” poster could be personalized with the provider’s photo and signature. Some providers indicate patients expect antibiotics even if the illness is viral (where antibiotics would not be effective) so NYSDOH developed a “Get Smart Guarantee” palm card [PDF – 1 page]. This takeaway serves in lieu of a prescription for antibiotics so patients understand their concerns have been heard and validated. The poster and palm card are offered in English and Spanish.

Utah Department of Health: Using Data to Identify Best and Worst Performing Clinics

The Utah Health Department shared data publicly on the Open Data Catalog website to show which clinics in the state had the best and worst performance on the HEDIS® measure: Avoidance of antibiotic treatment in adults with acute bronchitis (which usually does not require antibiotics). Utah used its All Payer Claims Database, which combines eligibility, medical claims, pharmacy claims, and provider files each month, to compile 2013-2014 data.

What can healthcare providers do to support appropriate antibiotic use and prevent infections in outpatient settings?

- Follow clinical guidelines when prescribing antibiotics.

- Use the right antibiotic, at the right dose, for the right duration, and at the right time.

- Place written commitments in support of improving antibiotic use in exam rooms to help facilitate patient communication about appropriate antibiotic use.

- Give patients information and materials on appropriate antibiotic use to reference. See examples of print materials for everyone.

- Talk to patients and families about when antibiotics are and are not needed, and discuss possible harms such as allergic reactions, C. difficile, and antibiotic-resistant infections.

- Ask patients if they have ever had a C. difficile infection, and tailor antibiotic treatment accordingly.

- For patients with conditions that usually resolve without antibiotic treatment:

- Talk to patients about ways to relieve their symptoms without antibiotics.

- Discuss a clear plan for follow-up if symptoms worsen or do not improve.

- Be aware of antibiotic resistance patterns in your community; use the data to inform prescribing decisions.

- Follow hand hygiene and other infection prevention measures with every patient.

What can patients and families do to support appropriate antibiotic use and prevent infections in outpatient settings?

- Talk to your healthcare provider about when antibiotics will and won’t help, and ask about antibiotic resistance.

- Talk to your healthcare provider about how to relieve symptoms.

- Take antibiotics only when prescribed and exactly as prescribed.

- Don’t save an antibiotic for later or share the drugs with someone else.

- Insist that everyone cleans their hands before touching you.

- Stay healthy and keep others healthy by cleaning hands, covering coughs, staying home when sick, and getting recommended vaccines.

What Do We Know About Antibiotic Use In Nursing Homes?

Current data on antibiotic use in nursing homes is limited so the information here is based on a few small studies. Over the course of a year, approximately 4 million individuals receive care and services in a nursing home. Antibiotics are some of the most commonly prescribed medications in nursing homes with 50 to 70 percent of residents receiving an antibiotic over the course of a year.12,13 Up to 75 percent of antibiotics prescribed in nursing homes are prescribed incorrectly.12,13 The most common prescribing problems in nursing homes are using an antibiotic when not needed, choosing the wrong antibiotic, and using the correct antibiotic but for the wrong dose or duration. Prescribing problems can lead to harm including side effects, allergic reactions, C. difficile infection, and antibiotic-resistant infections. This is especially concerning because nursing home residents are already at high risk for getting a C. difficile infection.

From December 2013 to May 2014, CDC examined the medical records of nine U.S. nursing homes in four different states to assess how many antibiotics residents received in a single day and the documentation for those prescriptions. Researchers found that 11 percent of nursing home residents were on antibiotics on any single day. One in three of these antibiotic prescriptions was for the treatment of urinary tract infections; yet at least half of these prescriptions were for either the wrong drug, dose, or duration. Finally, 38 percent of orders for antibiotics lacked documentation of one or more important prescribing elements.14 CDC is launching a study with a larger number of nursing homes and pursuing partnerships with nursing home networks, pharmacies, and other companies to identify where action is needed most.

To protect nursing home residents, in 2015 CDC released The Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes. By adapting hospital recommendations to the nursing home setting, the Core Elements guide provides practical ways for nursing homes to initiate or expand antibiotic stewardship activities. The guide provides examples of how antibiotic use can be monitored and improved by nursing home leadership and staff. The companion checklist can be used to assess policies and practices already in place and to review progress in expanding stewardship activities. CDC works to provide support and technical assistance

to health departments and nursing home partners to help implement the Core Elements in nursing homes.

Leadership Commitment

Demonstrate support and commitment to safe and appropriate antibiotic use in your facility.

Accountability

Identify physician, nursing and pharmacy leads responsible for promoting and overseeing antibiotic stewardship activities in your facility.

Drug Expertise

Establish access to consultant pharmacists or other individuals with experience or training in antibiotic stewardship for your facility.

Action

Implement at least one policy or practice to improve antibiotic use.

Tracking

Monitor at least one process measure of antibiotic use and at least one outcome from antibiotic use in your facility.

Reporting

Provide regular feedback on antibiotic use and resistance to prescribing clinicians, nursing staff and other relevant staff.

Education

Provide resources to clinicians, nursing staff, residents and families about antibiotic resistance and opportunities for improving antibiotic use.

CDC collaborates with partners to implement appropriate antibiotic use efforts at a local level. CDC funds and supports many state and local health departments and other partners across the country to implement targeted antibiotic stewardship improvements in nursing homes.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health: Reducing C. difficile through Educational Interventions in Nursing Homes

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health extended C. difficile prevention activities from acute care hospitals into nursing homes. Sixteen nursing homes implemented multi-faceted educational interventions to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use for asymptomatic bacteriuria (when bacteria are found in urine without causing symptoms of a urinary tract infection). They conducted inperson trainings on antibiotic use for urinary tract infections and engaged patients and families. After one year, nursing homes experienced:

- Improved urinary tract infection diagnostic practices with a 28 percent decrease in unnecessary urine cultures for patients who did not have symptoms of urinary tract infection.

- Decreased antibiotic use with a 37 percent reduction in antibiotics given to patients experiencing asymptomatic bacteriuria.

- Improved patient outcomes with a 47 percent reduction in healthcare-acquired C.difficile infections.

Presbyterian Senior Care Network: Implementing the Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes

Presbyterian Senior Care Network is a network of senior care and independent living facilities in Erie, Pennsylvania. The first Antibiotic Stewardship Program team was initiated by two nurses focused on quality care and infection prevention and control. They anticipate all Presbyterian Senior Care Network communities will adopt the program over time. Their activities are based on CDC’s Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes.

State Policies to Improve Antibiotic Use in Nursing Homes

- State of California: Requiring Antibiotic Stewardship in Nursing Homes

California Senate Bill 361 required skilled nursing facilities to adopt and implement an antibiotic stewardship policy by January 1, 2017. According to the bill, the antibiotic stewardship policy should be consistent with CDC’s Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes. California was the first state to enact legislation to improve antibiotic use in nursing homes.

What can healthcare providers do to support appropriate antibiotic use and prevent infections in nursing homes?

- Follow clinical guidelines when prescribing antibiotics.

- Use the right antibiotic, at the right dose, for the right duration, and at the right time.

- Review antibiotic therapy 2-3 days after it is started based on the resident’s clinical condition and microbiology culture results.

- Talk to residents and their families about when antibiotics are and are not needed, and discuss possible harms such as allergic reactions, C. difficile and antibiotic resistant infections.

- Ask residents if they have ever had a C. difficile infection, and tailor antibiotic treatment accordingly.

- Be aware of antibiotic resistance patterns in your facility and community; use the data to inform prescribing decisions.

- Follow hand hygiene and other infection prevention measures with every resident.

What can residents and families do to support appropriate antibiotic use and prevent infections in nursing homes?

- Talk to your healthcare provider about when antibiotics will and won’t help, and ask about antibiotic resistance.

- Ask what infection an antibiotic is treating, how long antibiotics are needed, and what side effects might happen.

- Ask what your nursing home is doing to protect you from antibiotic-resistant and C. difficile infections.

- Insist that everyone cleans their hands before touching you.

- Ask visitors and family not to visit when they feel ill.

- Get vaccinated for flu and pneumonia, and encourage others to stay up-to-date on vaccines.

What Do We Know About Antibiotic Use In Hospitals?

- Improving Antibiotic Use in Hospitals

- Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship For Hospitals

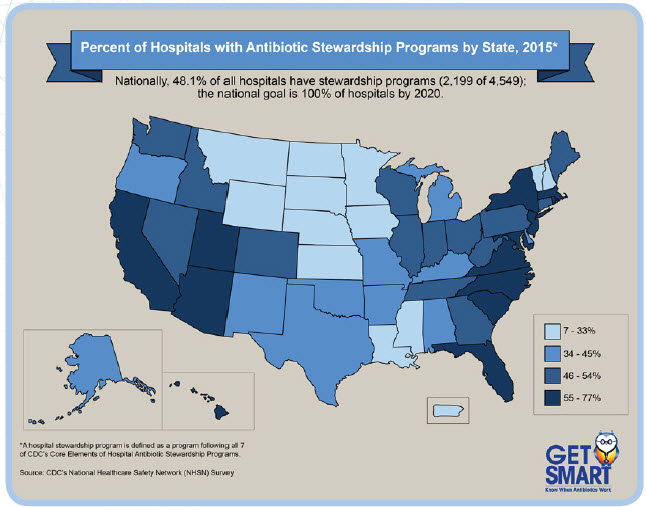

- Percent of Hospitals with Antibiotic Stewardship Programs by State, 2015

- CDC’s Standardized Antimicrobial Administration Ratio (SAAR): Assessment Tool Offers Step for Improvement

- CDC collaborates with partners to implement appropriate antibiotic use efforts at a local level.

- Healthcare Providers, Patients, and Families Play a Critical Role

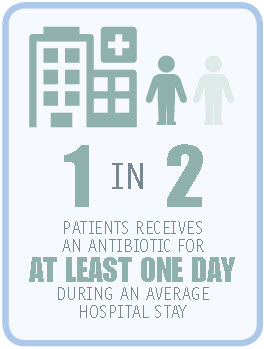

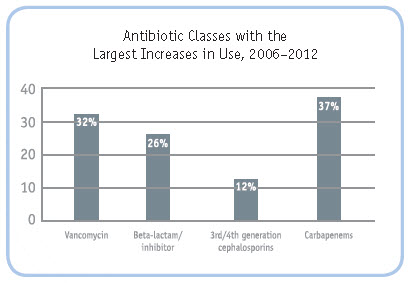

In a 2016 study, CDC experts found that overall rates of antibiotic use in U.S. hospitals did not change from 2006-2012. More than half of patients received at least one antibiotic during their hospital stay.15 However, there were significant changes in the types of antibiotics prescribed with the most powerful antibiotics being used more often than others. There was a 37 percent rise in the use of carbapenems. Infections caused by bacteria that develop resistance to carbapenems can be especially hard to treat, and even deadly. There was also a 32 percent rise in the use of vancomycin, an important antibiotic used to treat common antibiotic-resistant infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus, or MRSA. Data from CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network Antimicrobial Use Option show healthcare providers in some hospitals prescribe up to three times as many antibiotics as providers in similar areas of other hospitals. This variation suggests there are opportunities to improve prescribing practices.tibiotics in hospitals.

One-third of antibiotic prescriptions in hospitals involve potential prescribing problems such as giving an antibiotic without proper testing or evaluation, prescribing an antibiotic when it is not needed, or giving an antibiotic for too long.16 The National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria [218 KB] sets a goal that all hospitals have antibiotic stewardship programs to help reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions by 20 percent by 2020.

A national survey of antibiotic use done by CDC’s Emerging Infections Programs identified key opportunities to reduce inappropriate use. This study found that two out of three antibiotics in hospitals are given for three conditions: pneumonia, urinary tract infections (including bladder and kidney infections), and skin infections.17 There are data showing a variety of ways to improve antibiotic use in treating these conditions, so targeting them could have a large impact on improving appropriate antibiotic use. Likewise, studies have shown that there are many opportunities to improve the use of vancomycin and fluoroquinolones, two of the most commonly prescribed an[/cdc_textbox]

In 2014 CDC recommended that all acute care hospitals implement antibiotic stewardship programs. CDC’s Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs provides a framework for establishing and improving antibiotic stewardship in hospitals. Since their adoption, the Core Elements have been used as an implementation framework by large health systems and have become part of The Joint Commission’s accreditation standard for antibiotic stewardship.

Leadership Commitment

Dedicating necessary human, financial and information technology resources.

Accountability

Appointing a single leader responsible for program outcomes. Experience with successful programs show that a physician leader is effective.

Drug Expertise

Appointing a single pharmacist leader responsible for working to improve antibiotic use.

Action

Implementing at least one recommended action, such as systemic evaluation of ongoing treatment need after a set period of initial treatment (i.e.“antibiotic time out” after 48 hours).

Tracking

Monitoring antibiotic prescribing and resistance patterns.

Reporting

Regular reporting information on antibiotic use and resistance to doctors, nurses and relevant staff.

Education

Educating clinicians about resistance and optimal prescribing.

The Core Elements were designed to be flexible enough to be adopted in hospitals of any size. In 2016, CDC partnered with the National Quality Partnership of the National Quality Forum, a not-for-profit, nonpartisan, membership-based organization that works to catalyze improvements in health care, to lead a team of experts in creating a practical guide to help hospitals implement the Core Elements. The Antibiotic Stewardship in Acute Care: A Practical Playbook provides real-world strategies to help hospitals and health systems of all sizes implement and improve antibiotic stewardship programs.

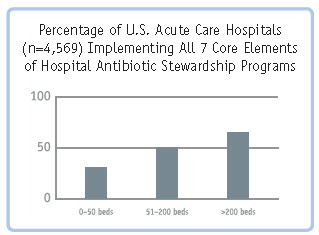

CDC has been assessing the implementation of the Core Elements through the NHSN Annual Survey. In 2014, 41 percent of hospitals reported implementing all seven elements. By 2015, that had increased to 48 percent. However, there were important differences in implementation, with larger hospitals showing much more uptake: 66.1 percent of hospitals with over 200 beds reported all seven Core Elements, compared to 49.6 percent of hospitals with 51–200 beds and 31.1 percent of hospitals with 1–50 beds. Data from this survey indicate that there is much more to do, especially in smaller hospitals which face special challenges in implementing the Core Elements. CDC partnered with The Pew Charitable Trusts, the American Hospital Association and the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy to develop Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Core Elements at Small and Critical Access Hospitals to support the implementation of stewardship programs in these hospitals.

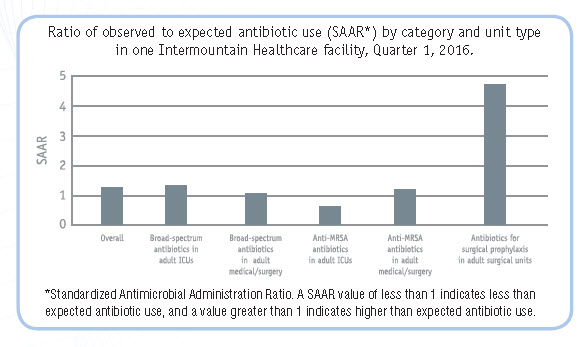

While the SAAR cannot be used to measure the appropriateness of antibiotic use in a hospital, it can be used to direct hospital antibiotic stewardship programs to areas where antibiotic use deviates from what is expected. A high SAAR signals a need for further review to see if there are opportunities to improve use. CDC collaborated with The Pew Charitable Trusts and a number of experts to develop an assessment tool to help hospitals find opportunities to improve use in locations with high SAARs. Though the tool is designed to be used in conjunction with the SAAR, it could be used to look for improvement opportunities in any location where stewardship programs believe use is higher than expected. For more information on the SAAR and strategies to assess antibiotic use in hospitals, visit Strategies to Assess Antibiotic Use to Drive Improvements In Hospitals [PDF – 460 KB].

CDC collaborates with partners to implement appropriate antibiotic use efforts at a local level. CDC funds and supports many state and local health departments and other partners across the country to implement targeted antibiotic stewardship improvements in hospitals.

Ascension: Building the Infrastructure for Antibiotic Stewardship in a Large Health System

Ascension is the largest non-profit health system in the United States, with facilities in 25 states and the District of Columbia, including 141 hospitals and more than 21,000 acute care beds.

Ascension has made swift progress in its antibiotic stewardship efforts by implementing four strategies in support of full implementation of CDC’s Core Elements in all Ascension hospitals:

- Making antibiotic stewardship a system priority with full leadership support.

- Creating an infrastructure to promote and share best practices.

- Promoting the careful use of narrow-spectrum antibiotics (antibiotics that are specifically effective against a limited number of bacteria).

- Helping hospitals achieve their goals by investing in clinical decision support systems, strengthening local expertise, and tracking and evaluating antibiotic use data.

As a result of these efforts, Ascension has seen reductions in antibiotic use and 15.9 percent reduction in C. difficile infections. One 376-bed teaching hospital drove a 70 percent drop in the use of selected antibiotics over a six-month period.

Intermountain Healthcare: Using Data to Identify Opportunities for Improvement

Intermountain Healthcare is a not-for-profit health system based in Salt Lake City, Utah, with 22 hospitals, about 1,400 primary care and secondary care physicians at more than 185 clinics in the Intermountain Medical Group, and health insurance plans from SelectHealth. Intermountain Healthcare has been an early adopter of the NHSN Antimicrobial Use Option and has been using the data for action. For example, they identified one facility that had an overall antibiotic SAAR measure indicating use was as expected, but found one very high SAAR – for antibiotics used for surgical prophylaxis on adult surgical units—indicating higher use of these antibiotics than would be expected. This highlighted a specific area for further exploration and improvement.

Southwest Health System (SHS) serves about 50,000 people in rural southwest Colorado, and in parts of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, and the Ute Mountain and Navajo reservations. SHS has 25 inpatient beds and 8 clinics. SHS has made antibiotic stewardship a priority through a variety of strategies while implementing CDC’s Core Elements:

- Creating a stewardship team of hospital leaders, including laboratory professionals, physicians, pharmacists, infection preventionists, nurse educators, and a wound care specialist.

- Using pharmacists to lead the antibiotic stewardship program. Pharmacists also work to decrease risk of C. difficile by adjusting medications.

- Educating hospital staff and providing feedback through active daily rounding where staff discuss medications, antibiotic choice, duration of therapy, and discharge medications.

- Collaborating with partners in a state-wide antibiotic stewardship collaborative (including implementation of a urinary tract infection (UTI)/upper respiratory infection (URI) stewardship program in SHS’ eight clinics) and seeking efforts to expand stewardship to local long-term care organizations and dentists.

The Richard L. Roudebush Indianapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center: Using NHSN Data to Evaluate a Stewardship Activity

The Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center located in Indianapolis, Indiana, is a general medical and surgical hospital and teaching hospital with 150 beds. The organization used CDC’s NHSN Antimicrobial Use Option to evaluate their hospital stewardship program. Infectious disease physicians and clinical pharmacists tracked and reviewed antibiotic usage in their hospital and gave feedback to providers. They used NHSN data to track antibiotic use before and after the intervention and identified a hospital-wide decrease in antibiotic use, as reflected in lower SAAR values, especially in anti-MRSA agents and antibiotics used for

hospital onset infections, which were targets of their reviews.

State Policies to Improve Antibiotic Use in Hospitals

- California: California Senate Bills 739 and 1311 require hospitals to develop a process for monitoring antibiotic use and implementing antibiotic stewardship. California was the first state to enact legislation to improve antibiotic use.

- Missouri: In addition to requiring all Missouri hospitals to create antibiotic stewardship programs, Missouri Senate Bill 579 (passed in 2016), requires that all non-psychiatric hospitals must begin reporting antibiotic use to CDC’s NHSN by August 2017.

- Follow clinical guidelines when prescribing antibiotics.

- Use the right antibiotic, at the right dose, for the right duration, and at the right time.

- Review antibiotic therapy 2–3 days after it is started based on the patient’s clinical condition and microbiology culture results.

- Talk to patients and families about when antibiotics are and are not needed, and discuss possible harms such as allergic reactions, C. difficile and antibiotic-resistant infections.

- Ask patients if they have ever had a C. difficile infection, and tailor antibiotic treatment accordingly.

- Be aware of antibiotic resistance patterns in your facility and community; use the data to inform prescribing decisions.

- Follow hand hygiene and other infection prevention measures with every patient.

What can patients and families do to support appropriate antibiotic use and prevent infections in hospitals?

- Talk to your healthcare provider about when antibiotics will and won’t help, and ask about antibiotic resistance.

- Ask what infection an antibiotic is treating, how long antibiotics are needed, and what side effects might happen.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you have been hospitalized in another facility or have recently taken antibiotics.

- If you have a urinary catheter, ask daily if it’s necessary.

- Ask what your hospital is doing to protect you and your family from antibiotic-resistant and C. difficile infections.

- Insist that everyone cleans their hands before touching you.

- Get vaccinated for flu and pneumonia, and encourage others to stay up-to-date on vaccines.

References

- Vital Signs: preventing Clostridium difficile infections. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2012; 61(9): 157-62.

- Dantes R, Mu Y, Hicks LA, et al. Association Between Outpatient Antibiotic Prescribing Practices and Community-Associated Clostridium difficile Infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015; 2(3): ofv113.

- Kutty PK, Benoit SR, Woods CW, et al. Assessment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance definitions, North Carolina, 2005. Infection Control And Hospital Epidemiology: The Official Journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America 2008; 29(3): 197-202.

- Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015; 372(9): 825-34.

- Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS. US Emergency Department Visits for Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2016; 316(20): 2115-25.

- Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013; 4: CD003543.

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescriptions Among US Ambulatory Care Visits, 2010-2011. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2016; 315(17): 1864-73.

- McCaig LFH, L.A.; Roberts, R.M.; Fairlie T.A Office-Related Antibiotic Prescribing for Persons Aged < 14 years—United States, 1993-1994 to 2007-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011; 60(34): 1153-6.

- Shapiro DJ, Hicks LA, Pavia AT, Hersh AL. Antibiotic prescribing for adults in ambulatory care in the USA, 2007-09. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2014; 69(1): 234-40.

- Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, Sande MA. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001; 33(6): 757-62.

- Hersh AL, Fleming-Dutra KE, Shapiro DJ, Hyun DY, Hicks LA, Outpatient Antibiotic Use Target- Setting W. Frequency of First-line Antibiotic Selection Among US Ambulatory Care Visits for Otitis Media, Sinusitis, and Pharyngitis. JAMA Internal Medicine 2016; 176(12): 1870-2.

- Nicolle LE, Bentley DW, Garibaldi R, Neuhaus EG, Smith PW. Antimicrobial use in long-term-care facilities. SHEA Long-Term-Care Committee. Infection Control And Hospital Epidemiology 2000; 21(8): 537-45.

- Lim CJ, Kong DC, Stuart RL. Reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the residential care setting: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 165-77.

- Thompson ND, LaPlace L, Epstein L, et al. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Use and Opportunities to Improve Prescribing Practices in U.S. Nursing Homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2016; 17(12): 1151-3.

- Baggs J, Fridkin SK, Pollack LA, Srinivasan A, Jernigan JA. Estimating National Trends in Inpatient Antibiotic Use Among US Hospitals From 2006 to 2012. JAMA Internal Medicine 2016; 176(11):1639-48.

- Hecker MT, Aron DC, Patel NP, Lehmann MK, Donskey CJ. Unnecessary use of antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: current patterns of misuse with an emphasis on the antianaerobic spectrum of activity. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003; 163(8): 972-8.

- Fridkin S, Baggs J, Fagan R, et al. Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2014; 63(9): 194-200.

See Current Report