Tracking infections in food, water, and soil

No time to waste: Discovering telltale signs of COVID-19 in wastewater

Fragments of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, have been found in wastewater systems and can serve as an alarm bell for communities. Examining wastewater offers unique benefits. It’s efficient, because a pooled sample can reveal infection levels across an entire community. It can serve as an early warning system because fecal shedding (virus excreted in poop) can occur even before symptoms of infection appear. And it’s quick. Changes in infection levels in a community can be detected within a few days versus the 2-week lag for other types of surveillance data.

One group of NCEZID scientists is focusing on examining wastewater from nursing homes, since they are a major hot spot for COVID-19 and can amplify spread into the community. Finding SARS-CoV-2 in nursing home wastewater may help detect infections quicker and stop the spread of disease faster compared with the standard swabbing and screening of individuals when they enter a facility.

NCEZID experts, in collaboration with university and federal partners, evaluated the usefulness of wastewater surveillance for the COVID-19 response, posted technical considerations documents on CDC’s COVID-19 website, and built the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS). In FY20, the NWSS team provided emergency funding for external partners like universities, health departments, and wastewater utilities to facilitate communities of practice where expertise, lessons learned, and best practices can be shared across disciplines. We are poised to expand these systems in FY21. Public health officials can use NWSS data to rapidly identify presence and trends of COVID-19 within a community and get a head start on preventing its spread.

Valley fever and COVID-19: They may look similar, but one is a deadly fungus

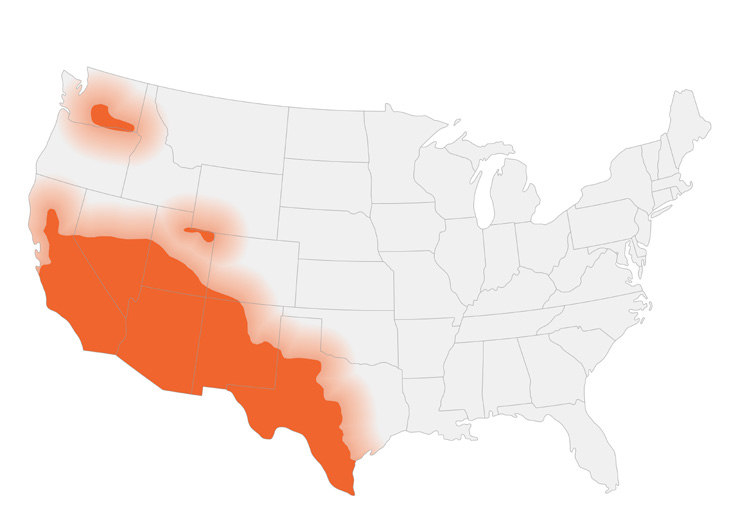

This map shows CDC’s current estimate of where the fungi that cause Valley fever live in the environment in the United States. The disease is also common in northern Mexico, including areas along the US border, as well as parts of Central and South America.

Valley fever is an infection of the lower respiratory tract resembling community-acquired pneumonia. The disease is caused by the fungi Coccidiodes, which live in the soil in the southwestern United States and parts of Mexico and Central and South America. The fungus was also recently found in south-central Washington. People get Valley fever by breathing in the microscopic fungal spores from the air, although most people who breathe in the spores don’t get sick.

The problem is that Valley fever can look like other lung infections, including COVID-19. Fungal disease experts at NCEZID are working to educate the public and alert healthcare partners of the similarity in symptoms to ensure that Valley fever is not mistaken for COVID-19.

Causing more than crying

NCEZID foodborne disease experts were busy in the summer of 2020 snuffing out an outbreak of Salmonella Newport infections. The culprit causing this unusually large 48-state outbreak with 1,127 confirmed cases was red onions. But because of the way onions are grown and harvested, white, yellow, and sweet yellow varieties were possibly contaminated and included in a large recall. Despite the diversion of many state resources to the COVID-19 response, the outbreak was swiftly detected, investigated, solved, and controlled.